Small Schools, Big Issues

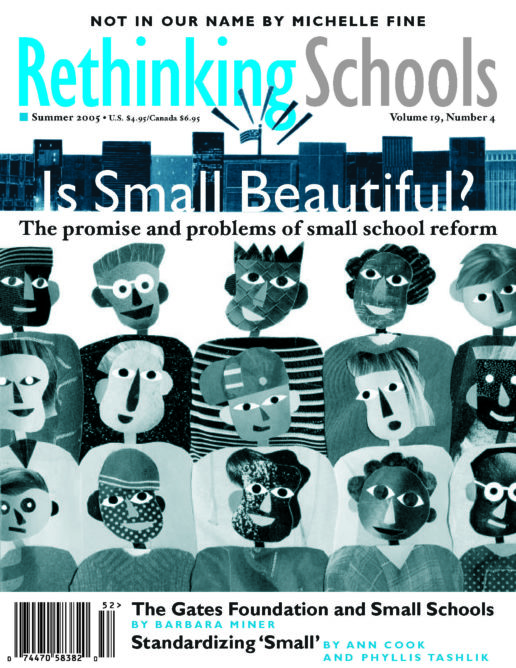

In this special issue, Rethinking Schools looks at the hottest trend in the all-too-trendy world of education reform: small schools. Reports and analysis from various locations and vantage points provide multiple perspectives on a reform strategy that has the potential to be a step toward educational justice or another wrong turn for education policy.

Small schools advocate Michelle Fine (“Not in Our Name”) speaks for the early proponents of “schooling on a human scale” who saw small as a metaphor for more collaborative, less authoritarian relations among students, teachers, and communities. These activist educators sought to create schools small enough to sustain a healthy, democratic decision-making process around issues of teaching, learning, governance, and allocations of time and resources.

They used thematic, interdisciplinary, inquiry-based approaches to develop innovative curricula that linked schools to student and community concerns, and in many cases, activism for social change. Fine sees all-too-little of these goals in current efforts to mass produce small school reform at the district and state levels.

Ann Cook and Phyllis Tashlik of New York City’s Urban Academy build on Fine’s analysis (“Standardizing Small”). They describe the school-based practices developed at Urban Academy and other “performance-based” small schools that can make “small” a framework for school improvement. But they add major cautions about how the misuse of standardized tests can suffocate the potential of small school reform and undermine its aims and effectiveness.

Deborah Meier, founder of Central Park East, one of the most universally cited small school models, reminds us (“Creating Democratic Schools”) that a democratic school culture, rather than top-down consultant-driven processes, is the key to better teaching and learning.

Barbara Miner (“The Gates Foundation and Small Schools”) reports on the dramatically growing role of the Gates Foundation in shaping small school reform. Her survey identifies some key issues and concerns raised by advocates for educational excellence and equity.

Reports from New York, Chicago, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Oakland, Portland, Ore., and Tacoma, Wash., provide examples of some of the most promising, and most problematic, aspects of small school reform. On the one hand we see how organized communities, enlightened union leadership, and committed educators can act to shape reform agendas and improve their ability to serve schools and communities. We can find hope in Héctor Calderón’s inspirational description of El Puente Academy for Peace and Justice’s efforts to use supportive small school relationships, integrated social justice curricula, and community activism to develop an educational vision for a better world.

At the same time, we can see in other reports how small school reform can be used in the service of privatization, resegregation, and top-down bureaucratic management, weakening public education and increasing inequalities.

Finally, Linda Christensen (“Rhetoric or Reality?”) reminds us that for all the many issues raised by small school reform, improving instruction in classrooms may be the toughest task of all.

For the most part, the range of school reform options currently up for debate on state and national stages is inexcusably narrow. There are fundamental issues of race and resources, democracy, and larger social purpose that are too often evaded instead of addressed by these efforts, including the small schools movement. But the fact remains that “small” is now increasingly paired with standards and tests as the framework for debate on middle and high school reform.

For all its limitations, this debate presents an opportunity to raise crucial questions about resources, equity, school climate, facilities, and, in some contexts, even the purposes and content of schooling. It’s an opportunity advocates for educational and social justice need to seize if small school reform is ultimately to deliver on its promises.