Simulating Redlining: When “Race Was the Real Currency”

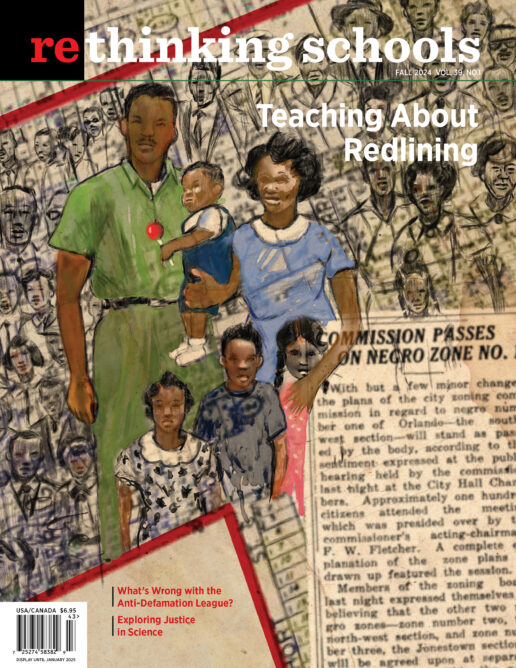

Illustrator: Howard Barry

“After learning about redlining, I can see it all around me now.”

Reading my student Lilliana’s words reminded me of my own experience encountering the history of redlining. I don’t remember when it was, but I remember what it felt like. Something in my head just clicked — the streets that seemed like an invisible barrier between Black and white, the stark differences I’d observed between cities and their surrounding suburbs — the racialized physical environments I had grown up in, lived in, and worked in, all suddenly made sense. Growing up I was told that the South was where you’d find segregation, where the legacy of racism shaped the fabric of social and political life. But I spent most of my life living in cities — Los Angeles; Portland, Oregon; New York City; Philadelphia — profoundly shaped by decades of racist redlining policies and practices.

Before working for Rethinking Schools, I taught African American history to sophomores at Central High School in Philadelphia, a uniquely diverse academic magnet school in one of the most segregated cities in the country. In fact, according to analysis of the 2020 Census, a majority of the top 10 most segregated cities and metropolitan areas in the country are outside of the South. And segregation was never only about the physical separation of people, but also the vast inequalities between different racial groups. Unless we teach the history of racist housing policies that have led to white people holding 10 times the wealth of Black people in the United States, students will be more susceptible to racist arguments that blame Black poverty on individual and cultural failings.

As I began crafting my unit on redlining, I wanted to figure out how to simulate the way decades of redlining practices led to segregation and dramatic wealth disparities. I knew from running lessons like Bill Bigelow’s Thingamabob Game (posted at the Zinn Education Project website) that when students experience an aspect of the political economy, they grasp the dynamics at work much clearer than they would otherwise. This was confirmed repeatedly by students in their end-of-unit reflections. “Having experienced it firsthand, my understanding is not only deeper but also more ingrained,” Anna wrote. Classroom simulations are often the lessons that stick with students — the ones they talk about at the end of the year and when they come back to visit after graduating. But figuring out exactly what facet of redlining I wanted to simulate was more complicated than I had anticipated.

Redlining is now popularly associated with the maps created in the 1930s by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a New Deal-era government agency. These maps gave letter grades to neighborhoods in nearly 230 U.S. cities on a scale from “Best” (A) neighborhoods, assigned the color green; “Still Desirable” (B), assigned the color blue;“Definitely Declining” (C), assigned the color yellow; and “Hazardous” (D) neighborhoods, assigned the color red. Lower grades of C and D indicated to banks and investors that mortgages or investments in these areas would be risky. Investment poured into A and B areas and was almost universally withheld from C and D areas. But what the rating system really indicated was the race and class character of the neighborhoods — and the racism and classism of those who graded them. The racism of HOLC geographers was such that even solidly middle-class African American neighborhoods were labeled red.

While the term redlining is derived from these maps, the term tends to encompass much more. As I was crafting the simulation, I exchanged several emails with Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, whose work heavily influenced my thinking. In one email he wrote, “The HOLC maps are graphic and easy symbols of government racial policy. But they are given much too much attention in discussions of racial inequality and its origins.” Rothstein emphasized that the maps merely “described the segregation of the city,” but the government policies that exacerbated segregation and led to the dramatic wealth disparities we see today more than anything else were the VA and FHA granting of amortized mortgage loans (something that was extremely rare or nonexistent before the Great Depression) almost exclusively to white families to move to the suburbs.

This is the policy I chose to highlight in the simulation. While it was certainly not the only racially discriminatory policy and practice we now refer to under the umbrella of “redlining,” it was one of the most consequential. Therefore, the simulation was an introduction to the topic that allowed my students to have a firm grasp of key concepts related to redlining in order to free them to explore further. The unit allowed them to peel back the onion of government policies and practices layer by layer to reveal the racist core that shaped and continues to shape our physical landscape.

Preparing the Simulation

To prepare for the simulation I created a set of slides to track what occurred. I made the background for the first two slides out of a Philadelphia redlining map. I put the image through a photo app that “comicified” the map, making the colors more vibrant and the borders between neighborhoods a bit more dramatic, and then I stretched it across the slide.

A day before the simulation, toward the end of the period, I broke my class into 10 groups of three to four students. The large number of groups made the simulation feel a little unwieldy as I was recording results every round on the slides, but it was important to have many families on the map so students could get a strong visual of the segregation taking hold during the simulation. “Next class we’ll be simulating the effects federal housing policies that started in the 1930s had on Black and white families,” I told my students. “Some groups will go through the simulation as white families, others will go through the simulation as Black families. We’ll discuss how these experiences differ at the end.” I went around the room assigning at random each group a race and a number that corresponded to one of the 10 houses on the simulation board. It was spring, and by this point in the year, my students had become accustomed to activities in which they take on different identities from their own. I explained that this was not a role play and that the assigning of race in this activity was simply to take note of the ways race shaped opportunities and limitations for families during this time.

I had each group spin an online color wheel (linked in the “Simulation Instructions” provided with the digital version of this article) to determine what section of the map their family started in. “There is a different color wheel for white families than for Black families,” I explained. “Choose one person from your group to click on the link assigned to your family, spin the wheel, and let me know what color you land on — that will be your starting point in the simulation tomorrow.” As I began putting houses in their respective spots on the map, one student realized that the color wheel for Black families only had two colors — red and yellow — and the color wheel for white families included three — red, yellow, and blue. “That’s not fair!” he exclaimed. “Black families are only in the red and yellow areas.” “That’s the point!” Taylor and Matana, two students next to him who had already heard of redlining, declared in unison. “Right — what we’re doing tomorrow is to try to simulate what happened as a result of these federal housing policies and learn from that,” I confirmed. “Because many of these housing policies were unfair, many of the rules in this simulation will also be unfair. The point here is to see if simulating what happened — experiencing a little bit of it — can help us better understand it.”

Running the Simulation

The next day I projected the simulation map on the board with the results from the color wheel spins the previous day, despite the different color wheels, the majority of white and Black families started in the red and yellow areas. “This is what our city looks like at the start of our simulation,” I proclaimed. “We’ll return to this map at the end and see how things have changed.”

I asked students to quickly get into their groups and I handed out the simulation instructions. The instructions are broken up into five key sections that we read through and discussed: “Home Values,” “Loans,” “Racial Covenants,” “Income,” and “Debt.” Like any simulation, the rules oversimplify complex processes, and after the simulation it’s important to make space to help students unpack that. After we defined what it meant for a home to “appreciate” in value we read the first section on “Home Values,” which explains the initial worth of each home, and how homes in different areas appreciate differently each round. The simulation ends after round six (each round represents six years). Home values appreciate based on where they are located:

- Red area: Home values appreciate by 1 percent per year

- Yellow area: Home values appreciate by 2 percent per year

- Blue area and green area: Home values appreciate by 4 percent per year

- Suburbs: Home values appreciate by 5 percent per year

I chose appreciation rates that seemed to reasonably mirror historical reality based on the data I could find, but appreciation (and occasional depreciation) rates varied widely. After clarifying with students that home values appreciate a lot each round, because each round represents six years (in order to simulate 30 years in total), I assured students that they would not have to calculate how much their home appreciated during the simulation as I had already calculated that for them on the slide for each round.

As the next section explains, “White families that are not in debt (do not have negative wealth) can receive a 30-year home loan of $50,000 and a 5 percent interest rate to move to the suburbs.” I emphasize to students that this is a new opportunity the government helped set up in the wake of the Great Depression. Previously, the only people who had home loans were wealthy and banks typically wanted to be repaid in five to seven years. But a new kind of home loan was set up during the Great Depression that allowed homeowners to take a much longer time to pay off their loan and bundled the home value with the interest so as homeowners were paying it off they owned more and more of their home. “So if you can, you want to take advantage of this opportunity and do it as soon as possible,” I told students, “because the longer you wait, the more expensive homes are going to get.” I created “loan cards” and printed them out on cardstock, so students could keep track of their payments.

“Wow! Look at all those people moving to the suburbs!” Jasper exclaimed once we started the simulation. “We should move out to the suburbs too because their houses are going up more.” argued Mahady. They decided to take out a loan.

As it did historically, this policy had the most dramatic effect on increasing segregation and the wealth gap. Red and yellow areas begin relatively integrated (indeed, according to one study, redlined areas were 85 percent white in 1930) but within one or two rounds, most white families had taken advantage of the loan to move out to the suburbs — increasing segregation and eventually, leading to large wealth disparities.

The next section explained that “Blue neighborhoods and the suburbs have racial covenants that forbid developers and owners from selling homes to non-whites.” In reality, covenants existed in all sorts of neighborhoods but in the 1948 Shelley v. Kramer decision the Supreme Court said that they could not be enforced in court. But regardless of whether homes had racial covenants, the real estate industry was committed to racial segregation. No realtor would sell a home to a Black family in a white neighborhood. This is something I would draw out in our debrief discussion, but I determined would be too complicated to simulate.

In the simulation, the racial covenants and the high prices of homes in the green areas prevent Black families from moving out of the red- and yellow-colored neighborhoods. My student Chris expressed his frustration with this during the simulation: “Ugh! We can’t get enough money to move into the green, we can’t get a loan to go to the suburbs, and the covenants prevent us from moving into the blue!”

The last two sections of the instructions explain what is most relevant for students during the simulation:

Income: At the beginning of each round someone in your group will roll a six-sided dice. Your roll will determine your income for the round. This is your family’s net income after six years and will carry over into the next round. Because white families have better access to higher-paying jobs, dice rolls produce unequal incomes:

White families

Black families

1: –$20,000

1: –$20,000

2: –$10,000

2: –$10,000

3: 0

3: 0

4: $10,000

4: $5,000

5: $20,000

5: $15,000

6: $30,000

6: $25,000

Debt: Low dice rolls may put you into debt. Debt only becomes significant as part of your total wealth. If your debt becomes greater than the value of your home, you must sell your house to the bank to pay off your debt.

In one class when I ran the simulation, after taking out a loan to move to the suburbs, students representing a white family had two bad rolls in a row. “Oh no! We’ve got negative income!” Angela worried. David, another student representing a Black family next to them was outraged. “What? I can’t believe you’re complaining!” he exclaimed. “You’ve got negative income but look how much more wealth you have than us because of your home.” David then paused, turned to his partner, sighed, and with eyebrows raised, sarcastically stated, “Such white privilege!”

Each round students rolled the dice and recorded their income, home value, and wealth on a worksheet that gives them step-by-step instructions for how to make their calculations. When they finished, they handed their worksheet to me and I recorded the answers on the simulation slideshow so everyone could see the income, home value, and wealth of each group. The only choice families had to make during each round was whether they wanted to move (if they could). Anytime someone moved to a new location, I recorded that on the second map slide so at the end of the simulation students could compare what our community looked like at the beginning and end of the simulation. But after the first two rounds, most families were locked into their neighborhoods.

The simulation itself took two 53-minute periods plus one more for our debrief discussion. The first rounds go a little slower as students are getting used to the rules and calculations and many of those representing white families will need help as they take out loans. When I do it again, I plan to ask for a volunteer who would help me collect worksheets and maybe record calculations on the slide to free me up to focus more on groups that needed help. In every class, the simulation results were similar and illuminating: The relatively integrated map we had started with became increasingly segregated as white families fled to the suburbs taking advantage of the low-interest loans available to them. This also led to dramatic wealth disparities with white families typically ending the simulation with $100,000–$200,000 more wealth than Black families.

On the final day of the simulation, before they left the classroom, I asked students how they felt. Marianni, who is Puerto Rican, said, “I liked being white. You didn’t have to worry. You never went into debt too much. You could really see where all that wealth comes from.” Jayden, who is Black and represented a Black family that did relatively well during the simulation, stated, “It helped me realize why neighborhoods look like they do now and how Black families are locked into certain neighborhoods. My family can’t move out of our place because everywhere else is too expensive and my mom makes decent money.”

Debriefing the Simulation

Students clearly had fun during the simulation, but I wanted to get a clearer sense of what they had learned and give them an opportunity to connect their simulation experience to historical reality. To start our debrief the following day, students wrote on and we discussed the following questions:

- Describe what went on in your family group. What decisions did you make? Why did you make those decisions?

- How did the simulation make you feel? Why?

- Find a person who was in a group that was assigned a different race than yours. What was their experience like? How was it different or similar to yours?

Although some students were already comparing experiences during the simulation, I wanted to make sure that students who were assigned the role of a white family got to hear about the experience of those who were assigned a Black family and vice versa. Melanie described the frustrating experience of Black homeowners: “We didn’t buy anything because we didn’t have enough money and we weren’t allowed to take out loans,” she said. “We were also very scared of going into debt because we could lose our house. Meanwhile, the white families were able to immediately move out from the red and yellow areas into the suburbs. The simulation made me feel hopeless and sad that it was so unfair for Black families. Seeing the white families’ wealth go into triple digits made me want to stop playing because they were clearly going to be the richest!” Bianca concurred: “I felt excluded,” she wrote. “Our group was making a lot less money than others around us, and we were stuck in the same place for 30 years trying (and failing) to build wealth.”

Meanwhile, those who were assigned white families had mixed feelings about what had happened. “The simulation kind of made me feel superior to the other families because we made money so easily and were able to move to the suburbs,” Zoe admitted. Others like Ankit, felt guilty about the ease at which they had accumulated wealth. “It made me feel dirty. I was a part of a white family that started in the red area, but we could get a loan and move to the suburbs. High rolls and increased income for whites allowed us to pay off the loan quickly and accumulate wealth from home appreciation. But Black families could not do this,” he wrote. “Kamera, next to us, was in a Black family. They were in debt for almost the entire time. Their home almost got repossessed by the bank. My family didn’t experience any of those issues.”

“Black families were locked out. How could you get out without reparations?”

To make sure students understood how the access to accumulation at this particular historical juncture reverberated into the 21st century, I created a final slide that showed what the results of the appreciating home values would be if we had continued past our six rounds — displaying more than 70 years of unfettered growth in wealth inequality. While the homes in the red area had doubled in value to just over $20,000, the homes in the suburbs had grown by 33 times their original price to more than $1.67 million. I asked students: “Look at the last slide that takes housing prices into the modern era. What were the results of the unfair rules of our simulation? How did these policies contribute to the racial wealth gap?”

“Black people and white people weren’t on equal playing fields and because of that white people were able to get ahead and create a lot more wealth,” Zoe wrote. “It seems like the farther a family got from the red area, the more wealth they were able to accumulate,” Elijah observed.

In our discussion, Natasha used a poignant metaphor: “It really showed how race was the real currency back then,” she stated. “That’s true even now,” Jayden replied. “Mmmhmm,” Natasha agreed, exchanging knowing nods with Jayden.

Before we jumped into looking at primary and secondary sources, I wanted students to understand that this was not inevitable. That there were policies that could have — and could still be — put in place to remedy the effects of redlining and create racial justice instead of exacerbating inequality. “Could the rules be changed in ways that would not lead to racist outcomes? What rules would you implement that would lead to racial equity instead of making racial inequality worse?” I asked.

“We should close banks and real estate companies that engage in racist practices,” Hannah thought. “Create higher-paying, more accessible job opportunities for Black folks, encourage banks to give fair loans to Black families, and allow anyone to move anywhere,” Oni listed. I wanted to push students further. “What if we did some of those things — it’s illegal to deny Black families loans now or prevent them from moving to certain neighborhoods. But we do that after decades of redlining had already taken place?” I asked. I once again showed students the slide that took home values into the 21st century and pointed roughly to what represented 1968, when the Fair Housing Act barred many redlining practices. “Let’s say we passed laws now that removed those barriers, would that be equitable?” Sophia shook her head. “After all those years with the homes appreciating in the suburbs, Black families were locked out not because of race, but because they couldn’t afford the homes,” she insisted. Grabbing a phrase we had discussed during our Reconstruction unit, she asked, “How could you get out without reparations?”

Connecting the Simulation to History

Finally, I asked students to read and annotate a series of primary and secondary documents to think through how the classroom simulation mirrored historical reality. The sources included:

- A model racial covenant promoted by the National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB) in their member code of ethics in 1927, along with the note that “Thirty-two states authorized state real estate commissions to revoke licenses of agents who violated the NAREB code of ethics.”

- A map of Philadelphia that overlaid red dots symbolizing racial covenants over the HOLC map of the city.

- Excerpts from the Federal Housing Administration’s Underwriting Manual, written to guide appraisers hired by the FHA to determine whether a loan should be granted to a particular applicant.

- A short excerpt from Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law that discusses how racial covenants and FHA and VA policies worked together to create white-only suburbs.

After the simulation, my students eagerly delved into these sources to figure out how much of their classroom experience rang true to reality. Ankit noticed that in the model racial covenant printed in the NAREB’s code of ethics, not only did it bar Black people from owning homes, it made sure to provide an exception for “janitors’ or chauffeurs’ quarters in the basement or in a barn or garage in the rear, or of servants’ quarters by negro janitors, chauffeurs or house servants.” “This is the mindset of a slaveholder!” he angrily wrote in the margin. Savannah was also outraged. “Code of Ethics!? There’s nothing ethical about it!” she noted.

Looking at the FHA’s Underwriting Manual, Hannah thought, “What a nasty way to word it!” when she read that the FHA encouraged home appraisers to take into consideration whether pupils at the local school represented “a far lower level of society or an incompatible racial element.” Ankit summarized: “Not only does the FHA’s own manual explicitly tell real estate agents to segregate different races and says that the race of the buyer must be the same race as the seller to ‘preserve the value of the house,’ but it basically criminalizes people of color and lower social classes by saying that all these measures have to be taken to ‘protect’ rich white people from these ‘adverse influences.”

In the excerpt from The Color of Law, students learned that not only did the FHA provide loans almost exclusively to white families to move to the suburbs, but also to developers that built white-only suburbs. The excerpt discusses the creation of Levittowns, which according to William Levitt testifying before Congress in 1957, were “100 percent dependent on government.” This was, “government-backed mass-produced segregation,” Hannah concluded. “How is this not against the Constitution?!” Melanie asked. Indeed, the main argument in The Color of Law is that it was.

“Based on the sources, how did the simulation resemble real life? What does this teach us? What was realistic and unrealistic about the simulation?” I asked students — though I wish I had separated out the first two questions, because most students focused on the similarities and differences. “Real life was similar to the simulation because neighborhoods were segregated, only white people got loans, and the government (the rule makers) was responsible for the problem,” Jayden pointed out. We discussed how the simulation focused on homeowners — a relatively privileged section of both Black and white communities — and left out renters. And as Vanida pointed out, “In the simulation it was only Black and white families, there are more races than that.”

The few students who did center the “What does this teach us?” question in their response wrote particularly powerfully. “The simulation and the sources made me realize how difficult it is and was for Black families to prosper because of all the rules limiting them,” Aria explained. “They couldn’t get loans, they couldn’t afford to move, and were in constant fear of losing their home or going into debt. The system was designed for them to fail.” Amelia, who had a budding systemic critique, claimed, “Creating a separation of space, money, and people was a way to maintain segregation, white supremacy, and capitalism. The simulation and the sources showed how home value was a defining characteristic determining wealth and therefore quality of life.”

After the Simulation

Now that students had garnered a basic sense of the key policies related to redlining, they were ready to go deeper. I followed up the simulation with Ursula Wolfe-Rocca’s phenomenal “How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century” (available at the Zinn Education Project website), which crucially attaches names and stories to the historical dynamics the simulation had introduced. It also teaches students how people fought back against these policies. After this, we spent a full class period watching the short 18-minute documentary Segregated by Design, narrated by Richard Rothstein. This is a fast-paced documentary that throws a lot of new terms at students, so I created a viewing guide for it (see teaching materials posted with the digital version of this article) that asks critical questions for each section. We regularly paused while watching and used the questions to discuss and clarify what students were seeing.

To wrap up the unit I borrowed a project from a colleague, Prentiss-Charney fellow Monique McKenney, and had students in groups, choose cities and create a PowerPoint presentation on the effects of redlining in that particular city and come up with potential solutions to repair the harm of redlining’s effects. Because the consequences of redlining reverberate to almost every aspect of city life, the problems and solutions included a wide range of contemporary issues: from adopting single-payer health care to solve the health crisis in low-income neighborhoods, to taxing corporations who are polluting formerly redlined areas to pay reparations, to siphoning money from over-policing to finance affordable housing.

What stuck out to me as I watched these presentations was how relatively easily my 10th-grade students were able to come up with a whole host of potential solutions — and funding sources — to address the lingering impacts of redlining. It made many students wonder, as Lilliana wrote in her end-of-unit reflection, “Why hasn’t the government done more to fix the effects of redlining?”

While we continued these discussions into our study of the northern Civil Rights Movement, the unit, and the simulation in particular, had a significant impact on students’ thinking. “I could feel the frustration when I was in the simulation,” Melanie wrote. “It helped me connect with what we were learning. This simulation was more personal and hands-on and stuck with me longer than a video or reading could.”

“This information has definitely changed the way I view poverty and racial inequality in America,” Elijah admitted. “While I was aware that impoverished neighborhoods were caused by racism and inequality, I now understand how these poor communities were created and maintained. I now believe that redlining is among the most responsible of injustices that have resulted in modern-day inequality.”

Armed with these conclusions, students can become changemakers in their communities. More of us must understand the ways our racist past continues to shape our racist present in order to become architects and activists for an anti-racist future.

For teaching materials related to this article, click below:

Simulation Power Point

Simulation Instructions and Handouts

Simulation Debrief Questions and Sources

Segregated by Design Viewing Guide