Silencing Teachers in an Era of Scripted Reading

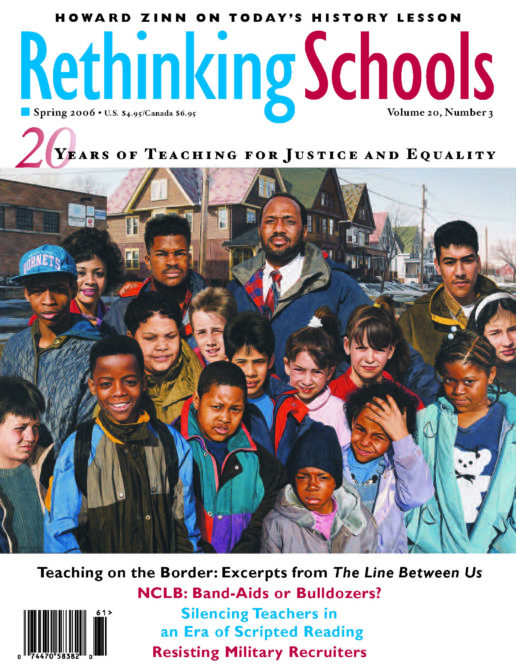

Illustrator: Roxanna Bikadoroff

“I have been told by the district that I will be transferred to another school effective Monday. I am very sad to be leaving you, but you are strong students and I know you will be successful. I have always taught you to stand up for what you believe in, and sometimes when you do that, there will be unhappiness. But in the end, you have to do what you feel is right. I will think about you every day and wish you all the best.”

I never would have imagined having to speak those words, yet there I was, standing in front of my class while the principal looking on silently. I had been forced out of the school where I had worked enthusiastically for more than five years because I had challenged required instructional practices that I believe interfered with teaching and learning.

Serving nearly 1,000 students, Downer is the largest elementary school in the West Contra Costa Unified School District, north and east of San Francisco. Its students are predominantly poor, non-native English speaking Latino children. I had been hired to work with teachers and students in an effort to increase achievement in reading and writing. Having provided after-school staff development the previous year, I was well known by the faculty. There was no get-to-know-you period; we hit the ground running. In my first two years we charted a long list of accomplishments. We developed a list of English Language Arts standards that we hoped all 6th graders would meet; an accompanying curriculum to promote these standards beginning in 4th grade; a Reading Block program in which we grouped upper graders by reading level and read short novels and related articles; a Challenge Class for students designated as gifted and talented; and Literacy Academy classes for struggling readers. These programs were based on several principles: that print knowledge and understanding of text develop in tandem, that teachers can adjust instruction to provide more support for less proficient learners, and that literacy is constructed in social settings rather than in teacher-imposed isolation.

Open Court Arrives

Then, in the spring of 2001, the school district adopted the Open Court reading series, a scripted reading program that tells teachers what to say and do at every moment. The following fall, the district began a rigid implementation of this program, insisting that teachers cover every detail of the curriculum. This occurred amidst the chaos caused by large numbers of teachers being removed from their classrooms to attend five-day trainings, often with no substitutes available.

Required by the district to spend two to three hours a day on Open Court instruction, teachers felt unable to include the literacy curriculum we had previously developed — curriculum that more fully addressed the range of levels and the varied strengths and weaknesses of our students. These students — full of energy and, by and large, eager to learn — became victims of a system that refused to teach them in the way they learn best: actively, holistically, and cooperatively.

In kindergarten and 1st grade, teachers now taught the least meaningful aspects of literacy — letters and sounds — and postponed emphasis on meaning for nearly two years. These children faced a steady diet of so-called decodable texts (“The cat sat on the mat. The cat is fat. Where is the cat?”). Teachers presented the lessons to all students at the same time, limiting the opportunity to differentiate instruction. Open Court also required a tremendous amount of “teacher talk,” limiting communication among children — especially problematic for English learners. Teachers got laryngitis while children remained silent.

In order to cover all the required lessons, teachers had to present the material at a very fast pace. This resulted in moving on through the curriculum even when students needed more time to understand the lessons. Frequent text-based assessments took up to 20 percent of instructional time. This over-emphasis on testing promoted teaching to the test rather than learning of greater substance. All of these factors reducedthe interaction between teacher and student to a mechanical and impersonal back-and-forth.

I wasn’t a classroom teacher, but my ability to serve teachers and students was severely affected by the adoption of Open Court. I couldn’t bring myself to demonstrate lessons from a program so inappropriate for our students. And, overwhelmed by the Open Court curriculum, teachers found little time for anything else. The struggling readers I saw in my pull-out intervention classes were further weakened by a curriculum that didn’t meet their needs. I was reluctant to speak freely about these difficulties in order to protect the small acts of resistance that classroom teachers took with my encouragement.

The following year, McGraw-Hill trainers and other outside consultants began entering classrooms at will — interrupting lessons, chastising teachers in front of their students, going through personal files without permission. If teachers veered from the Open Court script, altering less effective lessons or expanding upon those lessons, the principal threatened them with disciplinary action.

By spring 2004, teachers were demoralized; rather than discussing ways to facilitate learning, teachers focused on how to make it from day to day. Children were either bored or frustrated, since there was virtually no opportunity to meet their individual needs. Administrators grew increasingly rigid, focusing on things like whether teachers had posted sound/spelling cards in the correct place.

It is important to note here that not all teachers in our district fell victim to the heavy-handed implementation of Open Court. Teachers in other schoolstold methey were allowed great flexibility in use of the materials and advised by their principals to focus on standards rather than on the scripted teacher’s guide. Policing by consultants was minimal. How did these schools differ from Downer? They were located in middle-class neighborhoods with a greater percentage of white students. The district shackled teachers of poor children with generally lower achievement to a curriculum that did not let them modify their teaching. Teachers in more affluent schools could enrich the curriculum to emphasize higher-level thinking and aesthetics. These students had the opportunity to obtain an education that prepared them to assume demanding leadership roles. Poor kids received an education that prepared them for McDonald’s, McMilitary, and Mc-Prison.

Resistance Grows

In spring 2004, I think most teachers at Downer shared my concerns about Open Court. They spoke privately about their frustrations and concerns for their students, but, fearful of possible repercussions, most were less vocal than I. They chose other forms of resistance. They closed their doors and did what they could to make the curriculum more responsive to the needs of their students. The district hired a new principal in the fall of 2005, the fifth in six years. He removed me from my position as literacy specialist and placed me in a 6th grade classroom, stating that I was unable to effectively support bilingual teachers since I didn’t speak Spanish. Later he admitted to one of my colleagues that the actual reason had been my opposition to Open Court. Despite teachers’ efforts to work together with administration to improve literacy instruction, school climate deteriorated over the course of the year.

In August 2005, the regional superintendent asked me to meet with yet another new principal. At that meeting, district administrators told us that they had listened and learned their lesson; they had chosen this person because she was willing to share decision-making with our staff. A short time later, our faculty watched a video made by the acting superintendent and president of the school board stating that they had realized that top-down management was ineffective and that theywanted to work with teachers to improve our district. We took these leaders at their word.

It soon became evident to nearly everyone on staff that the new principal was struggling. She had great difficulty managing a large, complex school community. Meetings were neither effective nor efficient. She had trouble solving even the simplest of daily problems.Through all of this, my colleagues and I repeatedly volunteered our help. We offered ideas for inservice trainings, assistance with discipline, a plan for organizing the student study team, and help in mentoring newer teachers. The principal refused or ignored our efforts.

On Oct. 5, 2005, after attending a speech by author and activist Jonathan Kozol, four other teachers and I were inspired to take further action. After repeated efforts to establish a collaborative relationship with administration in the district, we regretfully determined that more of the same would not prove successful. So the only option available to us was to state what we believed, what we hoped would change, and, finally, what we could no longer do in good conscience. We wrote a letter to our colleagues offering to assist with several of the school’s most intransigent problems such as school governance and after-school programs. Specifically, we refused to:

- Administer an English language development assessment that required teachers to spend 45 minutes working individually with each child while other students worked independently (this would mean 12 to 15 hours of missed instructional time).

- Attend weekly staff development meetings. Despite contract language stating that at least three meetings per month were to be jointly planned by teachers and administration, the principal had developed each agenda.

- Allow Literacy Coaches to provide 20 minutes per day of phonics instruction in heterogeneous 4th grade classrooms; this was over and above the approximately 10 minutes per day of phonics required in the Open Court lessons. If we were to follow this practice, phonics would total 25 percent of the daily instructional minutes in literacy.

- Attend ineffective literacy trainings that would require us to leave our students with a substitute for up to a week at a time.

We didn’t want to tell any other teachers what to do, nor put them at risk of reprisal, so we didn’t actively solicit other signatures.

Repression and Hope

Within a few weeks, district administrators rectified the first three of these concerns; they deemed the ELD assessment and 4th-grade phonics lessons voluntary and agreed with the union that the issue of co-planned meetings had been resolved in a previous grievance. We were never told to attend any trainings during the school day. Neverthe-less, the repercussions began. First, the principal told us that we could not use the intercom system to announce our meetings, and then that we were not to meet at all on school grounds. She stated that we could not rebut the handouts that Literacy Coaches put out to defend their practices by putting a response in teachers’ mailboxes, nor even provide research articles that offered another perspective. Next, the principal called several of us into her office and threatened us with possible disciplinary action. Then, she sent us warning letters, full of inaccuracies. Soon thereafter, the district personnel department transferred me and another teacher to other schools. Despite vocal and public protests by teachers, parents, and community activists — as well as grievances filed on our behalf by the union — the transfers have not been rescinded.

Never once throughout years of effort to advocate for our predominantly poor, non-native English-speaking students has any district administrator ever said, “These seem like intelligent, committed educators. Maybe they have something of value to offer.”In a culture strongly influenced by the punitive regulations of the No Child Left Behind act — a culture of fear, threat, and retribution — administrators evidently viewed us only as troublemakers.

There are signs of hope. We’ve received messages of support from across the country. School board members have expressed a desire to begin genuine dialogue. Activist groups such as Justice Matters and Teachers for Social Justice in San Francisco have invited us to speak about the widespread teacher silencing and the tyranny of scripted reading programs.

Nevertheless, a clear message has been sent to any teacher in our district who might contemplate taking a stand that might be unpopular with administration: Speak up and you will be punished; advocate for your students and you will be silenced.

If this situation were unique to one school in one district, it might not be worthy of much attention. But it is not an isolated case. Whatever the original intentions of No Child Left Behind, the result is that more children are being left behind than ever before, and this is especially true of poor children and children of color. In an effort to raise achievement by standardizing curriculum, the implementation of this law has robbed teachers of the opportunity to act on their professional judgment. Teachers who know better are teaching scripts instead of children because they fear the consequences of opposition to these policies. In this atmosphere of mistrust and intimidation, how easy will it be to move forward in our efforts to serve the children entrusted to us?