Shape-Shifting Segregation Policies

Using Mexican American School Segregation to Discuss Structural Racism

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

At the end of class one semester one of my student teachers approached me to share what they thought they knew about the Mendez v. Westminster School District case — the 1940s Mexican American school segregation case. “I always thought about it as a Mexican American student case,” they said, “but I never stopped to think about how the case connects to other students of color.” This comment came after a lesson on Mexican American school segregation where I encouraged my preservice teachers to consider structural racism.

On this particular day, the teachers explored how Mexican Americans have been racialized as Black and white during different time periods to exclude them from white schools. The idea that Mexican Americans can be both shatters neat conceptions of race and ethnicity.

In centering the racialization process instead of specific people of color, this lesson untangles the multiple layers of discrimination that have perpetuated school inequality for decades. One of the ways I engage my class of preservice teachers is by interrogating primary and secondary sources. Together, these sources unveil how Mexican American students have been segregated as early as the 1910s. Overall, the lesson focuses on four themes:

1) How schools have manipulated race/ethnicity and language to limit access to quality education.

2) How these tactics were used to uphold white supremacy.

3) How communities of color have challenged such efforts through both grassroots and legal means.

4) How these challenges have had limited success.

The Changing Racial Classification of Mexican American Students

Most of my preservice students are familiar with Plessy v. Ferguson, so I usually begin there because the case solidified the segregation of children into Black or white schools. But where do other racial and ethnic groups fit into this binary? Mexican American children are not exclusively either, making it difficult for them to fit into the stereotypical Black/white binary. So I begin with a hook, asking the teachers “how might the ‘separate but equal’ doctrine and other school segregation policies apply to Mexican American children?” For many, it is the first time they’re confronted with this question, so they struggle a bit.

“They would be segregated to Black schools,” Julia quietly answered, unsure of her answer. Danielle countered, “But they’re not Black.” “But they’re not white,” Julia replied.

“This exchange accurately captures the dilemma for Mexican American children, so let’s figure it out together,” I said as I transitioned them to the next activity.

I divided teachers into expert groups of three or four where they read one primary or secondary document. The goal is for them to focus only on one document so they can delve deeply into the complexity of each of these segregation challenges. Individually, each reading gives them an opportunity to address moments of cognitive dissonance. After all, the idea that Mexican Americans might be considered racially Black or white is at odds with how we racialize Mexican Americans in the present. Participants need time to process the contradiction and why this might be.

I give the first group an excerpt from Rubén Donato and Jarrod Hanson’s “Porque tenían sangre de ‘Negros,’” which focuses on Mexican American children in 1915 Louisiana. Attempts to segregate Mexican American students were based on the argument that they were in fact Black. Another group received an adapted excerpt from Mark Brilliant’s The Color of America Has Changed, discussing how Mexican American families in 1940s California claimed whiteness to attend white schools. A third group is assigned part of Judge McCormick’s 1946 court ruling in Mendez that upholds segregation on the basis of language. The fourth group got an excerpt from Guadalupe San Miguel’s Brown, Not White, centering on 1970s Houston, where the school district claimed that since Mexican Americans were white, they could be integrated with Black students.

I asked the groups to analyze and discuss two questions: “What does the document tell you about how Mexican Americans were racialized? How did their racial category determine whether or not they were segregated?”

Mexican Americans Are Black

The first group, composed of Michael, Lucy, and Maggie, read about the 1915 Cheneyville incident, where school officials tried to segregate Mexican American children in Louisiana’s plantation country. “There were Mexicans in the South?” I overheard Lucy whisper to herself. Of course there were, but it was a small population, so Mexican American students were not a major concern until they became a significant number in schools. As the student teachers continued to read, they realized that one of the trustees of the Cheneyville schools learned that Mexican American children attended the local white schools. The trustee pushed for their removal on the basis that “they had ‘Negro blood,’” according to historians Rubén Donato and Jarrod Hanson. Experiencing a moment of cognitive dissonance, Michael turned to me in disbelief: “But this doesn’t make any sense. Mexican Americans aren’t Black.” Mexican-origin people are a mix of Indigenous, European, and African ancestry. They can look like Zendaya, Selena Gomez, or Emma Watson. But this racial understanding does not exist in the 1930s. Nor does Michael completely capture these nuances. But for a moment I leave the misunderstanding alone and ask, “So are they white?”

“Not really,” answered Michael.

“So what are they?” I asked.

“Mexican?” wondered Michael, noting that these options are limiting because they don’t capture the complexities of Mexican American identity.

“But that’s not really an option for them, is it?” I pointed out.

This hones in on the idea that the stereotypical Black/white binary makes no room for racial ambiguity, leaving Mexican Americans in a unique racial position. They are categorized as if they’re one racial group when they are in fact not one race.

Mexican-origin parents sought to alleviate the issue by seeking the help of the Mexican Consulate to give children access to an education. In the end, it is unknown how this incident in Cheneyville was resolved, or if it was resolved at all. This always frustrates teachers. “But how did it end?” Maggie asked. “It’s not about how it ended, but about the process,” I remind her. “Keep thinking about the larger picture.” The lack of clarity can be challenging, but this activity works best when I let teachers stew in ambiguity.

Mexican Americans Are White

The second group also has to grapple with a similar moment of cognitive dissonance, but this time the binary pushes Mexican Americans to claim whiteness. Beth, Julia, and Rachel read about the 1945 case, Mendez v. Westminster School District. In 1940s California, where there was a significant population of Mexican American students, school districts established “Mexican schools.” But school segregation policies didn’t specifically list Mexican Americans, so school districts had to find other means to segregate Mexican American students. Parents had to then find their own unique forms of circumventing attempts to segregate their children.

These unique circumstances came to a head in 1945 in Westminster, California. The Mendez family tried to enroll their children at their local elementary, the 17th Street School, but were denied admission because they were Mexican American. The Mendez family filed a class action lawsuit against five school districts. The Ninth Circuit Court ruled that because Mexican American children were white, they had the right to attend white schools. I can always tell when teachers reach this point of the reading because all of a sudden I see a lot of “thinking face emoji” expressions. This bewilderment comes from the fact that this doesn’t make sense given how we think of Mexican Americans today or how Mexican Americans have benefited from whiteness.

Further complicating matters is that the Mendez ruling did not strike down the existing state educational code that prohibited Asian American and Native American students from attending white schools. This adds another twist that the small group has to grapple with. “Am I reading this right?” asked Julia. “It sounds like the case desegregated Mexican Americans, but not other people of color?”

“Did it really desegregate them though? What do the documents say?”

The teachers go back to the reading. “Well, according to the document they got to go to white schools,” Beth answered.

Rachel challenged her. “Yeah, but if you read the section before, it says that the court agreed Mexican Americans were white.”

Julia reconsidered: “So it’s like still saying whites and whites can go to school together because Mexican Americans are now white. Isn’t that still kinda racist?”

In benefiting a select few, school officials could feign being inclusive while continuing to deny students of color access to a quality education. This rubs against everything we’ve learned in U.S. history classrooms because it doesn’t align with the narrative of racial progress. Like I reminded the first group, “Don’t just focus on the ending. Think about the process. What did the courts do? What did this mean for Mexican American children and students of color?”

Mexican Americans Don’t Speak English

The third document, unlike the other documents, elicited strong emotional responses from this batch of preservice teachers: Monica, Rose, and David. Judge McCormick’s 1946 Mendez decision reveals something that the previous document did not discuss: Mexican American children were considered inferior for allegedly not speaking English. The document begins “The only reason for segregation practices is the English language deficiencies of some of the children of Mexican ancestry.” Teachers quickly identify the language as deficit-oriented. It’s difficult to hide given that the second sentence reads “Spanish-speaking children are retarded in learning English.” The reactions are usually swift and clear.

“OMG! How can they speak about children that way?” yelled Monica.

“That’s sooo racist,” shouted Rose.

“Yes, it is. Tell me more about why you think that,” I replied.

After thinking about it for a minute, David finally spoke up. “Well, just because students don’t speak Spanish doesn’t mean they’re inferior. It means they speak a different language.”

This is true, but teachers miss an important point if they stop here. The Mendez children, like the other plaintiffs, were born in the United States. They were Mexican American, some of whom were actively discouraged from and penalized for speaking Spanish. As a teacher, I need to nudge my students to continue reading and make sure they don’t misidentify the children as Mexican immigrants.

“Wait, but did the judge say ‘immigrants’? How does he refer to them?” The small group scanned the text. “Children of Mexican ancestry?” asked David. “Right, ancestry. So whom is he referring to?” I asked. “Anyone who is from Mexico, including Mexican American kids,” answered Monica.

If students miss this little piece of information they will think that McCormick is referring to immigrant students and miss out on a key aspect of Mexican American discrimination. When school administrators could not segregate children on the basis of race, language became a new excuse. Mexican American children could still be segregated on the basis that they had “English language deficiencies.” This won’t become obvious to teachers until they compare documents and share notes with each other later. In this sense, Mendez outlines both white privilege and the racialization of language, how our ideas about languages are tied to people’s race and ethnicity. Speaking Spanish was considered inferior, but only because it is associated with deficit ideas about Mexican Americans.

Mexican Americans Are White, but for a Different Purpose

Twenty-three years after Mendez, school district officials used the “other white” legal strategy against Mexican Americans. The fourth group reads about this effort through the document that focuses on how the Houston Independent School District was required to develop a desegregation plan as a result of the 1970 Ross v. Eckels court decision. The school district argued that since Mexican Americans are white, they could be integrated with Black students. The district’s “integration” plan effectively left white students in white schools under the guise that they had met the requirement by integrating Black and Mexican American children. Amy, Kristine, and Kim were quick to identify how that was absurd. Kim began the discussion: “This is ridiculous, and it’s so obvious that Mexican Americans aren’t white.” Kristine followed up, “It’s clear that they’re just saying that so that the district can say they integrate schools, but not actually have to do it.”

Although this might be the most outlandish of all the legal arguments for justifying Mexican American segregation, it is one that the teachers understand well in large part because it is so nonsensical to them. People don’t usually consider Mexican Americans white, so it is easier for them to identify the school district’s argument as illogical. But for me it’s important to push teachers further. “Why would school administrators argue Mexican Americans are white?” I asked. Amy interjected quickly, “To keep Mexican American children out of white schools.” “Yup,” I replied, “people will say and do bizarre things to preserve white schools.”

Like Mendez and the Cheneyville incident, the issue was never Mexican Americans’ racial designation. School and district officials found creative ways to manipulate racial categories to ensure the end result was the same: excluding Mexican American children from white schools.

Can Mexican Americans Attend White Public Schools?

After teachers read and discuss the assigned document in their expert groups, I organize them into five jigsaw groups. Each group consists of one to two teachers who were previously focused only on one desegregation effort. In these groups teachers first share what they learned from their readings. Teachers use a handout with a table where they write notes on what others report regarding the other desegregation challenges. This helps get everyone on the same page, but the real learning happens through discussion. When teachers discuss the four documents collectively they bring greater complexity, exposing the insidiousness of structural racism.

To help them unravel the layers of complexity, I give teachers butcher paper and markers to create an infographic that answers the question “Can Mexican Americans attend white public schools?”

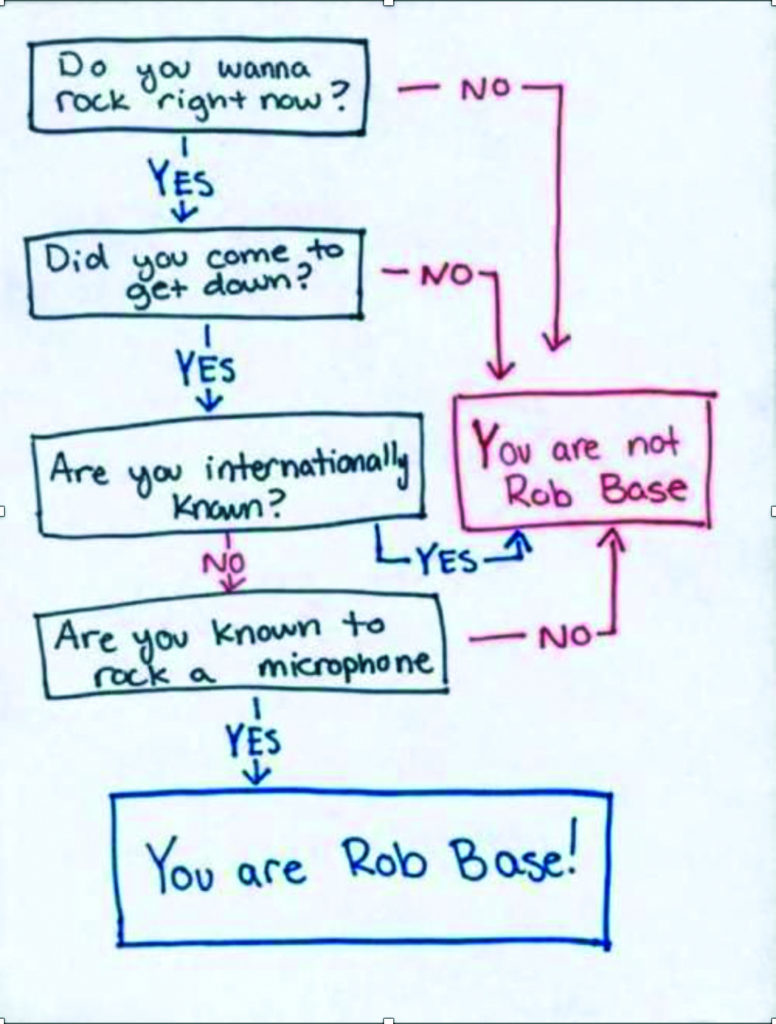

Most teachers are familiar with infographics but need a reminder, so I use this flowchart as a model. Based on Rob Base and DJ E-Z Rock’s 1988 hip-hop classic “It Takes Two,” the sample chart asks, “Are you Rob Base?” The infographic uses Rob Base’s lyrics to ask a series of “yes” or “no” questions. I usually get a good laugh from those familiar with the song. I’m a bit of a performer as a teacher, so I enjoy playing the song while pointing to the questions as they come up in the song and (horribly) rap along. I enjoy the giggles and eye rolls. More importantly, the model is straightforward and is limited to “yes” or “no” questions, just like the task instructions specify.

Using Rob Base as an example, teachers create their own infographics and flowcharts about Mexican American school segregation. During this activity I only have two requirements. The first is that teachers must answer the question only using the information from the primary and secondary sources they read. This keeps them on task and makes the assignment manageable given time limitations. The second is that I remind teachers that they need to use “yes” or “no” questions. This is purposeful, as it forces them to think in binaries, which reveals the oversimplified ways in which the United States has legalized and socially constructed race. This information will be useful later during the discussion and debrief.

The question “Can Mexican Americans attend white public schools?” is deceivingly easy. It’s phrased as a “yes” or “no” question, which makes it look simple, but this is actually one of the reasons why teachers find it infuriating. I hear “This is so much harder than I thought it would be!” multiple times. This is good! This means they’re grappling with the complexities. I worry when teachers draw a quick infographic because it means they’re not thinking across the different ways Mexican Americans were racialized. Take the following conversation between Beth, Michael, and Amy as an example.

Beth began with “OK, I think we should start with ‘Are you Black?’ because we know that Black students were segregated.”

“So if your answer is ‘yes’ then you can’t go to a white school. But what do we do if the answer is ‘no?’” asked Michael.

“Then we ask ‘Are you white?’” replied Beth.

Amy complicated matters arguing that “if Mexican Americans were considered white they still couldn’t go to white schools.”

“Right, the students in Houston couldn’t go to a white school,” Michael pointed out.

Beth offered an alternative: “What if instead we ask ‘Do you speak Spanish?’”

Amy problematized this question again: “But remember Dr. Santiago said that some students didn’t speak Spanish.”

Not all teachers will hit on this point, but when they do I ask follow-up questions. “If not all Mexican American students spoke Spanish, why would schools use this to segregate children?”

Beth was the first to reply. “Well, it’s not about what language they speak. It’s more like an excuse. Like we think Mexican Americans speak Spanish. So like speaking Spanish is synonymous with being Mexican American.”

“Right,” I agreed, “it’s a marker, a sign we use to identify someone as Mexican American. So we see this in Mendez. Mexican American children were considered legally white, but speaking Spanish ensured that they were not socially white.”

“Ugh, so then what do we add?” wondered Amy, incredibly frustrated by the constant obstacles.

The teachers are stumped because they’ve realized that no matter how they answer the infographic questions, a new obstacle arises. Every time they think they’ve figured it out, they get thrown a curveball. That’s because every time Mexican American families thought they’d have access to white schools, school officials would find a loophole. So the answer to the question “Can Mexican Americans attend white public schools?” is really a straightforward “no.”

The infographic, although fun and entertaining, reveals some complex realities about the racialization of Mexican Americans and race in general.

In this example, the teachers focused primarily on Mexican Americans’ shifting racial categories. But because there are multiple dimensions to Mexican American segregation that shifted according to time and local context, there are other ways teachers can draw an infographic. This is why I ask teachers to present their posters, to give participants an opportunity to see the various layers of racial and ethnic discrimination.

During the share out, Michael explained that “it didn’t matter if Mexican Americans were Black, white, or spoke Spanish. It was never about their race; it was always about keeping schools white.” “This is why the question ‘Are you white?’ loops back around because being white or Black never gave Mexican Americans access,” explained Beth. Amy added: “And why the question ‘Do you speak Spanish?’ returns you to the start because like being white was just another excuse to continue segregating Mexican Americans.” “Right,” I interjected to summarize their ideas, “school officials and judges manipulated the law to uphold white supremacy. When families of color challenged those policies, white school officials changed the rules of the racial game. People of color had to then adapt, changing their strategies to try to meet the moving target.”

The infographics represent the tangled web of lies Mexican Americans had to deal with and sets up the context for a powerful discussion. Given the complexity of the content, in this case less is more. For these reasons I usually only ask three discussion questions:

1. Can Mexican Americans attend white public schools? When? Why or why not?

2. What does the infographic tell us about segregation policies?

3. How do Mexican Americans’ racial ambiguity and language needs make it difficult for them to challenge segregation policies?

The purpose of these questions is to focus on untangling the racialization process. The discussion should not focus on individual segregation challenges, but more on the shifting segregation policies and how Mexican American communities tried to adapt to the shifting rules of the segregation game. When we discuss each challenge on its own, the conversation is limited to Mexican American school segregation. But when discussed as a whole system of discriminatory practices, then the conversation can focus on how race and ethnicity has been manipulated to protect white supremacy. This is the lesson that all teachers and their students need to learn. This is what makes this learning sequence on Mexican American school segregation not just about Latinidad, but also about the racial hierarchies that continue to exist in the United States.

REFERENCES

Brilliant, Mark. 2010. The Color of America Has Changed: How Racial Diversity Shaped Civil Rights Reform in California, 1941–1978. pp. 50-60. Oxford University Press.

Donato, Rubén and Jarrod Hanson. 2017. “Porque tenían sangre de ‘Negros’: The Exclusion of Mexican Children from a Louisiana School, 1915–1916.” pp. 34-35, 40. Association of Mexican American Educators Journal.

San Miguel, Guadalupe. 2005. Brown, Not White: School Integration and the Chicano Movement in Houston. pp. 134-135. Texas A&M University Press.

Santiago, Maribel. 2017. “Erasing Differences for the Sake of Inclusion: How Mexican/Mexican American Students Construct Historical Narratives.” Theory & Research in Social Education 45(1): 43–74.

Support independent, progressive media and subscribe to Rethinking Schools at www.rethinkingschools.org/subscribe