Preview of Article:

Science for the People

High school students investigate community air quality

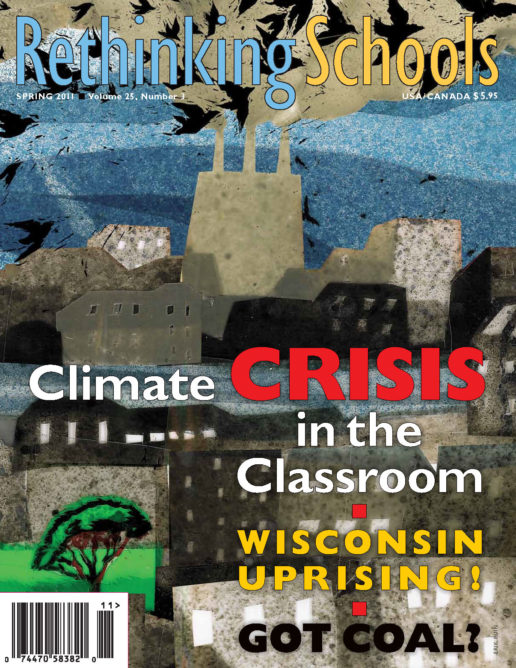

Illustrator: Michael Duffy

“Wow—Tony, look at those numbers! They’re like double the amount from before,” a student in our after-school science research program exclaimed after a large train passed by. The students were using a machine to count particulate matter (PM), microscopic particles primarily created through the combustion of various fossil fuels, along our air quality transect on Fruitvale Ave. in Oakland, Calif. What was once commonplace—a train speeding through the neighborhood—became a catalyst for students to understand the connections between energy and air quality.

Over a year, a small group of high school students risked their afternoons and summer to participate in a science program that was, as Maraya put it, “much different from science class.” This was one of several after-school programs in Oakland and Richmond that I was leading as an instructor with the East Bay Academy for Young Scientists (EBAYS), a National Science Foundation project coordinated by the Lawrence Hall of Science at UC Berkeley. Students in our projects carry out local, community-based research. Given the proximity of many schools to freeways, train tracks, and industry, we decided to focus on energy production and its relation to air quality as a way to help develop science literacy and environmental justice leaders.

With the help of the high school staff, I recruited a group of 9th graders. Many of them were struggling academically and wanted the extra science credit offered for my after-school project. Although we explained that they’d be researching air quality, students later told me that they did not know what they were getting into and joined primarily for the extra credit.

When we started, environmental (in)justice was not a part of their vocabulary, but it was a part of their experience. My challenge was to help students connect their visceral understanding of racial injustice to a scientific process that could be used to develop deeper knowledge about community health and air pollution. If they could collect and analyze data on air pollutants, and then communicate their findings and the implications to their community and others, this would be one step toward taking ownership of their environment and their community’s education.