School Board Journeys

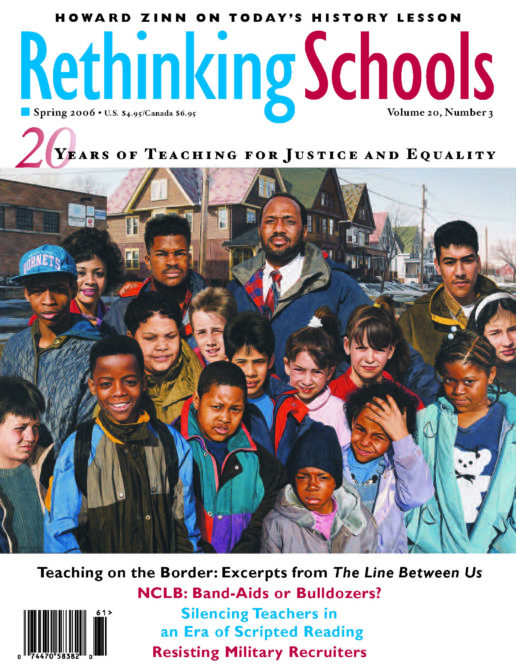

Illustrator: Susan Ruggles

In the early summer of 2001, fresh off my first election to a seat on the Milwaukee school board, I was invited to speak at a public school funding rally organized by students. In my opinion, the target for the rally couldn’t have been better chosen: the Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce (MMAC), a leading voice for publicly funded private school vouchers, school property tax freezes, and corporate-friendly tax policy.

The MMAC had campaigned hard against me, spending thousands of dollars to suggest that I was against needed reform of the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS), and that I was a pawn of the teachers union, among other charges. When I was handed the microphone at the rally in front of the association’s offices, I told the students that MMAC leader Tim Sheehy was like an abusive father, demanding more and more performance out of his children while denying them food.

A few weeks later, Sheehy invited me to lunch at his office. Over cold cuts, he asked me not to call him names, and suggested that I should try to keep the personal out of the political.

I agreed to not call names, but I didn’t give any ground on the other matter: School politics are personal. My children have attended MPS since kindergarten, and over the past decade I have seen the profound effects of budget cuts on their schools. Class sizes have gone up; parents are regularly begged for basic supplies like tissue and copy paper for their classrooms; and teachers’ salaries have stagnated. My elementary-aged son’s school has no gym or music teacher, and only sometimes has a librarian. The school funding crisis affects my family and my community every day, and it was the main reason I ran for school board.

Rethinking Schools, both the people and the publication, played a major role in my decision to run for office. I came to Milwaukee in 1991 thinking that I wanted to be an urban public school teacher. I also wanted to change the world, so it wasn’t long before I ended up at Rethinking Schools’ one-room office, ready to volunteer my services. I was thrilled to be in the company of teachers who were acting for social justice through their teaching. I started out helping with the typing and the proofreading, but soon was offered a paid position coordinating the marketing for False Choices, a new booklet on the voucher movement. Reading the stories that teachers around the country sent in for publication, I began to think that maybe I shouldn’t teach, but should instead focus on the organizing around schools that could change what happens both inside and outside those buildings.

I served as the journal’s editorial assistant until 1995, but I’ve always stayed connected with Rethinking Schools. My sons attended La Escuela Fratney, the two-way bilingual school that editors Bob Peterson and Rita Tenorio were instrumental in founding in 1987. At Fratney my children got the education I wanted for them, but I also got the chance to see the day-to-day struggles of gifted teachers trying to create a positive educational environment with too few staff members and inadequate funds.

It was clear to me that Milwaukee’s schools needed more money. It wasn’t so clear to the school board, particularly board president Bruce Thompson. MPS budget hearings were becoming near-riots, with hundreds of teachers, parents, and students futilely calling on the board to be more aggressive in getting resources from Madison (the state capital) and Washington. Thompson became infamous for imposing strict time limits on the public’s often emotional testimony. “Your two minutes are up,” he would interrupt them as they told of the financial crises in their schools. When teachers from Rethinking Schools approached me and asked me to run against him, I agreed. “Mr. Thompson, your two minutes are up!” became a rallying cry, and my marching orders from my new constituents were plain: Go find us more resources for our schools.

Wisconsin and Everywhere

Because of the state’s school funding formula, most Wisconsin districts are in severe financial straits, and some school boards are taking painful votes to field tax referenda or even to shut down or merge their districts. The Wisconsin school funding formula puts caps on how much districts may raise from the local property tax and how much we can pay our teachers, while also under funding critical programs like special education and bilingual services. Each district’s per-pupil budget is based on whatever they were spending in 1992, meaning that 14 years later there is an inherent divide between the buying power of a district that was a spendthrift in the baseline year and one that was fiscally conservative. That gap is on top of the typical chasm between a property-wealthy district and a poor one. As costs have risen and more performance demands have been placed on our schools, Wisconsin’s funding formula has become a formula for disaster.

I know that Wisconsin isn’t alone in this crisis and that meaningful school funding reform is a long, uphill battle. Writing for Rethinking Schools about 10 years ago, I developed an extensive listing of the school finance lawsuits that had taken place around the country. At the time, finance lawsuits had reached the highest courts in about half the states. A handful of these states have seen their courts or legislatures enact sweeping changes to their formulas, and some of these changes were themselves then challenged in court. Most states have had to wait as their elected leaders dragged their feet on reform, sometimes for decades.

Over the years, I’ve watched the conversation across the country turn from broad concern about equalizing educational opportunity to a more narrow focus on meeting the state’s curriculum standards. I’ve gone through this transition myself, and it’s one that makes me squirm in the tension between my Rethinking Schools spirit and the realities of being an elected official. Fighting the battle for adequate resources for Milwaukee’s schools today has sometimes meant setting aside for later the bigger philosophical and governance questions posed by an unequal and unjust society.

Addressing what Jonathan Kozol memorably called “savage inequalities” was the main goal of finance lawsuits in the 1970s and 1980s. In the most successful cases, spending on each student in a state was equalized, with adjustments for the disequalizing academic, social, and economic factors in children’s lives, such as poverty and special education needs. In the 1990s, after many funding lawsuits either were rejected at the high court level or produced rulings that got mired in political gridlock, finance reform activists began to rethink their arguments. Drawing on the era’s state standards movement, lawsuits began to demand adequate funding to cover the cost of bringing every student to proficiency on the state’s academic standards.

This new approach, usually called “adequacy,” is very logical. It appeals to people’s common sense and to the business-model reasoning that is so prevalent in government today. Adequacy activists often say, “When you decide to build a particular house, you need to cost out your materials and how much it will cost to pay the workers to build the house you’ve designed. You don’t design the house to specific standards and then expect you can get away without paying for the labor and materials to meet those standards.”

Equity is more a matter of fairness. We Americans say we believe that everyone is equal, and that equal opportunity is the bedrock of our society and economy, but we don’t actually live that way. Our society includes people with profoundly unequal histories, experiences, and environments. School funding debates make us ask ourselves uncomfortable questions about these differences and about our true commitment to equality.

I’ve had to ask myself some questions, too, such as, “How can I best use my elected position to get resources that the children in the Milwaukee public schools need today?” and “Should I struggle for ‘equity’ when I think only ‘adequacy’ is politically achievable right now?” and “Can I live with myself if I keep talking about ‘costing out houses’ when what I really want to ask is, ‘When are my city children going to be offered as well-funded an education as those in the wealthy suburbs?'”

A Compromise

After my election, I began working with a new statewide school finance reform group focused on adequacy, the Wisconsin Alliance for Excellent Schools (WAES). We have built a network of school districts, parent groups, teachers, religious organizations, business associations, and students to bring a united voice to the capitol. Recently, WAES successfully negotiated a merger with several other school funding reform groups, meaning we now represent wealthy and poor districts; urban, rural, and suburban districts; districts that are growing and ones that are shrinking. By bringing together groups that have used different approaches in the past, we have defeated our legislators’ cynical attempts to divide and conquer, but we still don’t have school finance reform. Wisconsin activists have also come to realize that the only way to get a new finance system will be to get a new legislature, so another statewide group is forming to strive to elect or un-elect legislators based on their stance on this issue.

When I talk about my position on school funding reform, I often say that I want to live in a country that truly values children, one in which the “children are our future” rhetoric our leaders throw around so easily actually means something. I want all of our children to get a high-quality education that prepares them to be informed and capable citizens of our complex world. I want all children to have an equal chance for success, regardless of what school district they’re born into.

I don’t live in that country yet, so I’m working for a system where, at minimum, we don’t demand anything from our children or our school districts that we’re not willing to pay for. As a school board member and as a mom, that’s a compromise I can live with — for now. Still, I know as long as Rethinking Schools is around, I won’t get away with it forever.

Schools.