Review: Radio Free Oaxaca

Illustrator: Pablo Sprecas Castells

Film

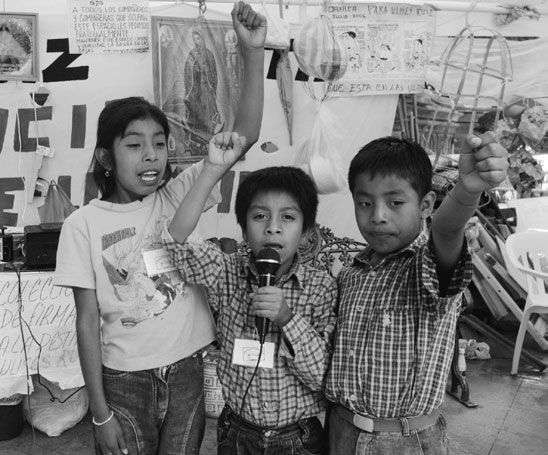

Photo: Pablo Sprecas Castells

Radio Free Oaxaca

Un poquito de tanta verdad

(A Little Bit of So Much Truth)

Director: Jill Freidberg

Corrugated Films, 2007

(www.corrugate.org)

DVD. 93 min.

By Kelley Dawson Salas

Un Poquito de Tanta Verdad (A Little Bit of So Much Truth) tells the story of how the 2006 teachers’ strike in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, became a mass movement that took over 14 radio stations and a television station, using the media to mobilize people and fight back against state and federal repression.

Producer, director, and editor Jill Freidberg also made This Is What Democracy Looks Like, about the 1999 World Trade Organization protests in Seattle, and Granito de Arena (Grain of Sand), about the rank-and-file teachers’ reform movement in Mexico. (For a review of Granito de Arena, see Rethinking Schools, Vol. 20, No. 1)

The teachers’ strike begins in May 2006 with the teachers establishing a plantón, or encampment, in the city center of Oaxaca. At the outset the strike lacks widespread public awareness or support, but the teachers use a radio station called Radio Plantón to spread their message, and when Oaxacan governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz cracks down on the striking teachers, the public’s disgust with the governor’s policies brings the people out in force.

Activists use Radio Plantón and another radio station called Radio Universidad to call on the Oaxacan people to carry out massive, nonviolent civil disobedience. The people set up more encampments to shut down nearly every government building in the capital city of Oaxaca, as well as 25 city halls throughout the state.

Then a women’s march descends on Channel 9, the state government channel. When the station denies the women’s request for an hour of airtime so that they can share “a little bit of so much truth,” the women occupy the station and run it themselves for the next three weeks. And when the state destroys the transmitters at Channel 9 and Radio Universidad, the people briefly take over 12 private radio stations so they can continue to get their message out.

The remainder of the film chronicles the escalating repression carried out by the state and federal government and shows how the movement uses the radio to mobilize and protect the people. The filmmakers have captured incredible footage including a scene in which a convoy of 4,000 federal troops headed to Oaxaca passes a march of several thousand Oaxacans headed to Mexico City; the takeover of the Oaxaca city center by federal police in riot gear; and the federal police’s failed attempt to use tanks to break down the gates of the university and attack Radio Universidad.

The narrator also provides other details of the repression, including stories of activists who were killed and disappeared, as well as those detained, tortured, and forced to go underground. People involved in radio were especially targeted. All the while the film shows how the people use radio to protect themselves by broadcasting the whereabouts and activities of police and para-police, and requesting immediate reinforcements when needed.

Also woven throughout the film are critiques of the mainstream media. People lament the media’s power to mesmerize and control people and its failure to report news accurately. Women explain how the media’s skewed reporting provoked them to take over Channel 9, and they threaten to take matters into their own hands.

The film’s focus on the media means that the teachers’ strike does not play as prominent a role in the film as perhaps it could. Though I wished for more details, it also felt good to simply see teachers participating alongside many other sectors in a mass movement for justice.

A more serious concern for teachers wanting to use the film in class is a lack of information about the conditions and history that led Oaxacans to take action in the first place. Teachers would need to find additional materials to help students gain an understanding of the social and economic conditions in southern Mexico.

But the film’s excellent coverage of a mass movement in a largely indigenous and poor part of Mexico, coupled with its critique of mainstream media and celebration of the people’s use of the media, make this a useful resource for the classroom and for teacher education courses.

Kelley Dawson Salas is a Rethinking Schools editor.