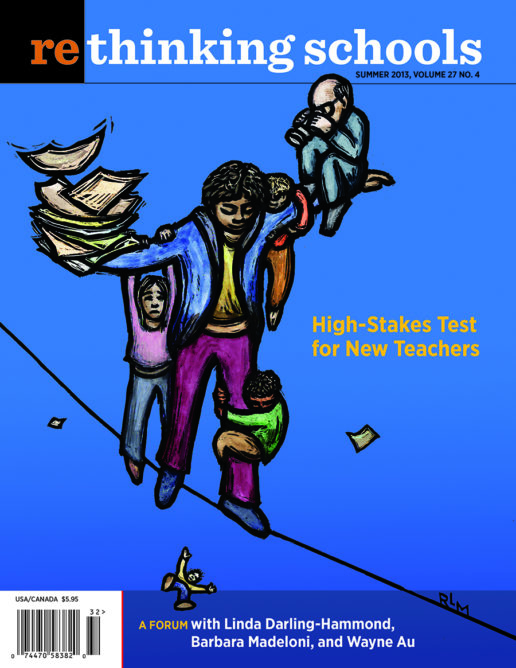

Rethinking the Day of Silence

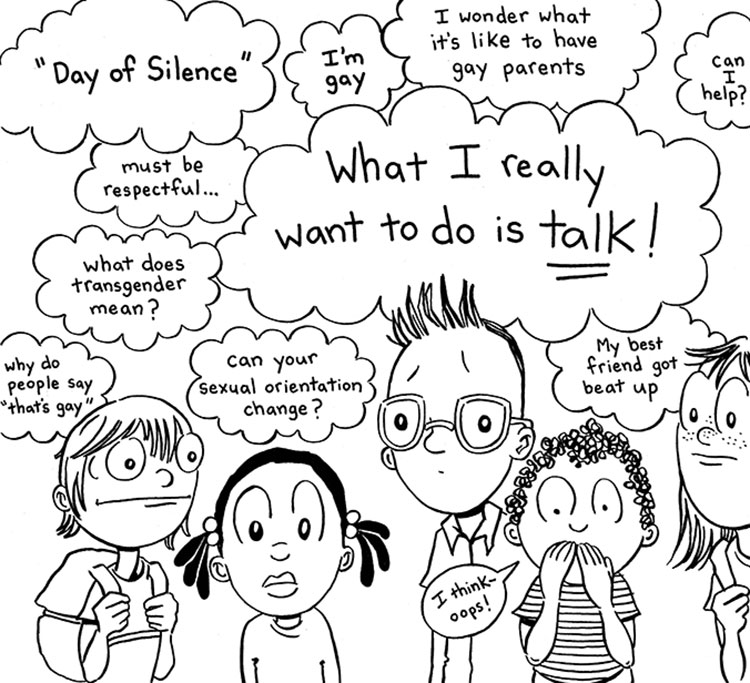

Illustrator: Ariel Schrag

Back in 2006, 7th and 8th graders at Green Acres, the K-8 independent school where I taught in suburban Maryland, participated in the Day of Silence. The Day of Silence is a national event: Students across the country take a one-day pledge of silence to show that they want to make schools safe for all students, regardless of their sexual orientation and gender identity/expression. The idea is for students to better understand—and to express solidarity with—people who feel they must remain silent about who they are. In theory, the event is a good one—after all, who doesn’t want students to develop empathy and understanding? But in practice, we found that the Day of Silence presented two fundamental challenges:

- Middle schoolers are not very good at being silent.

- Students wanted to know how their silence actually helped people who felt they weren’t free to be themselves.

Several students gave their best effort to remain silent for the day, but for the majority, an hour was the maximum. If the purpose of the day is to teach students how hard it is to be unable to fully express oneself, it did not take students more than an hour to figure that out. Telling middle schoolers that they are not allowed to speak is akin to telling teachers they can’t teach—it just goes against their essence. In that first year, we figured that perhaps we just didn’t enforce the “no talking” rule well enough, so we tried it again, but year two yielded the same results. When it came to LGBT topics, the students did not want to be silent—they wanted to talk.

The second challenge is the one that ultimately led our school to reinvent the Day of Silence as the Day of Action. At the end of our second Day of Silence, the director of diversity, the school counselor, and I debriefed the event with students. We wanted to know what, if anything, students gleaned from participating in the event and how we could make it better. We asked: How has the Day of Silence impacted your thinking about the freedom to be yourself? What changes would you recommend to the Day of Silence organizers? As we listened to students, it became clear that nobody wanted to name names, but that students were concerned about one of their classmates:

“I think the Day of Silence is a good start, but I want to know how to help. What if there was a student who was out at our school, but couldn’t come out at home? We might be the only safe place for that person.”

“We need to do something besides be silent all day. The Day of Silence should really be a Day of Action where we have different workshops and learn how to be allies.”

“Yeah! How does my silence help someone who doesn’t feel safe?”

There was a collective pause in the room. Among the student body, there was at least one student for whom the Day of Silence was every day and everyone knew it. The student felt safe at school, but not at home. For this student’s peers, understanding what it was like to be silent wasn’t the issue, figuring out what to do about it was. How could we, as a community, support this student? Surely, there were more students like this one. What could we do to ensure that our school was as safe and informed as it could be?

“What would be helpful?” I asked.

“First of all, let us talk! And then, rather than just hearing from each other and our teachers, let’s invite different speakers who we could talk to. Teenagers would be good. I want to know how to be an ally or what it’s like to be gay from a teen’s perspective,” pleaded a student.

Some students wanted to hear positive stories about LGBT teens instead of always hearing tragic stories of bullying and suicide. Many students wanted to know more about what it was like to come out, and how they could support their friends in the process. Students wanted practical tools to support their classmates and to make the school a safe place for all.

A Day of Action

The format of the Day of Silence needed to change. Students renamed the Day of Silence the Day of Action because they wanted to focus on actions they could take to support their LGBT peers and to stand up against bullying and discrimination. I met with the head of the middle school, the director of diversity, and the 5th/6th grade dean to discuss the changes that students were seeking. We agreed on a workshop format that would allow students to choose which sessions they wanted to attend.

So the day went from a struggle to be quiet to students participating in an array of workshops offered by community members, high school students, and Green Acres teachers, staff, parents, alumni, and trustees. Our speakers were recommended by and connected to Green Acres teachers and staff after I sent an email asking for family members, friends, and/or alumni who would be willing to share their stories of being LGBTQ or of supporting someone who is LGBTQ. We knew that one of the risks of inviting guest speakers to offer workshops was that we had less control over what they might say, but we also knew that authenticity had to be a pillar of the program for it to be successful. The trick, of course, was balancing honesty with how much middle school kids were ready to hear—in other words, being attuned to what was developmentally appropriate. When preparing the speakers for the event, we told them to share a story or an event—a coming-out story, a story about bullying, a story about being supported—and to focus on the emotions. We knew that not everyone in the audience could relate to their stories, but everyone could relate to being scared, nervous, rejected, hopeful, or loved. We wanted to show students that even amidst seemingly different experiences, there are human emotions that connect us all.

In our first year of running the Day of Action, we offered eight 35-minute workshops; students could attend two. After discussing the purpose of the Day of Action and reviewing workshop descriptions during advisory period, students made their selections on a Google form that asked them to rank their top four choices. The Google form automatically downloaded onto a spreadsheet that made it easy for organizers to place students in workshops by preference. Workshops included:

- Being an Ally

- How Words Can Hurt and What You Can Do About It

- Discrimination in the Workplace

- Coming Out: Teen Issues

- Being a Bisexual Mom

- Coming Out, Being a Gay Dad

- Marriage Equality in the News

- Supporting a Lesbian Daughter

When arranging the workshops, we had to balance student interest and need, available speakers, budget (speakers were unpaid, but we gave them a $20 gift card), and diversity of topics.

The day of the event, we found that the speakers were incredibly nervous, despite many of them having spoken in public before. The nervousness made the presenters unexpectedly more appealing to the students because it made them real. In one workshop, a speaker began to tear up as she talked about how hard it is to hear that kids tease her daughter for having a lesbian parent. A student in the audience spoke up and said: “That’s so mean. That’s why we have a Day of Action. I wish she could come to our school.”

In another session, students role-played what to say and what not to say when friends come out or share that they are questioning their sexual orientation or gender identity. In the session with local teens, one said: “This is actually a great place to be a gay teen. Montgomery County is one of the most accepting places in the country. It’s not perfect, of course, but there are a lot of accepting and supportive kids here.” At this point, I caught the eye of the Green Acres student who was open about his sexuality at school, but not yet at home. He gave me a nod.

After the two 35-minute sessions, we all came together to debrief the morning. When asked if they preferred this format to the Day of Silence, every student raised a hand. Some students said they learned how to respond to “That’s so gay.” Others offered insights on the impact of teasing and bullying; hearing it from the people who are affected made them realize just how awful it really is. A few students appreciated learning more about the (now successful) fight for marriage equality in Maryland. By far, the greatest hit of the day was the session offered by the teens. Even after we wrapped up the event, Green Acres students continued talking to them and asking questions. Lesson learned: If you want to capture the attention of middle schoolers, bring in a group of high school students to talk to them.

Parents Need Education, Too

Although the Day of Action was an overall success, it did not go off without a hitch. The new format raised concerns for some parents. Some believed that the topics were not developmentally appropriate for middle school students and responded by keeping their children home for the day. Others argued that the topic wasn’t “relevant” or questioned why we were focusing “so heavily” on this minority group. For an inclusive school like ours, these comments were highly unusual and unexpected. We realized that, unlike other topics of diversity, sexuality and gender expression force adults to confront religious and political beliefs that are sometimes far more complicated than the messages of understanding, respect, and safety that we saw the Day of Action as promoting. We saw the students addressing moral and ethical issues—how to treat others with respect, how to support peers who may be LGBTQ, how to use inclusive language, and how to stand up against bullying and/or discrimination—but the adults who were most concerned feared that we would focus on the physical aspects of sexuality, namely sex. Of course, nothing was further from the truth, nor would it have been appropriate.

In retrospect, we should have informed parents earlier and given them an opportunity to learn more about the program’s goals. Instead, we assumed we had communicated with parents clearly and that they would treat the Day of Action as any other school day. We assumed that because our school had a history of equality (we were the first racially integrated school in Montgomery County and on the forefront of publicly welcoming same-sex families to our school), our community would fully support making school a safe and welcoming place for all people, regardless of their sexuality or gender identity. What we learned was that sending letters out about the event was not enough. We had to offer parents the same opportunity we gave students to listen to stories about why a Day of Action was needed. We had underestimated the anxiety that some parents have about this topic.

To address parental concerns, the next year the school partnered with Family Diversity Projects, a nonprofit organization based in Amherst, Mass., that specializes in anti-bias education and professional development using traveling photo exhibits. We hosted the Love Makes a Family photo-text exhibit, which fights homophobia by telling the stories of ordinary people and by helping students to affirm and appreciate diverse family compositions. We invited parents to visit the display during an Evening of Action parent information session. Peggy Gillespie, the co-founder and executive director of Family Diversity Projects, was the keynote speaker for the Evening of Action and facilitated a panel discussion. With the exhibit as a backdrop, speakers discussed some of the same topics that students would explore at the Day of Action a week later. One of the parents who had kept her child home a year earlier came that evening to learn more about the day and its goals. Among the panelists were a local psychiatrist, an adopted gay teenage boy, and the straight son of two lesbian mothers.

A parent on the panel shared her regret at not replying to her gay colleague’s email the night before he committed suicide. “Education is our only hope,” she said, fighting to hold back her tears. “I wish every school had a Day of Action so that kids could actually listen to the stories of people they think are so different from them. Once you listen to someone’s story, it’s hard to hate.”

“I understand now. Thank you for sharing these powerful stories,” said the parent who had kept her child home. A week later, when the students’ Day of Action took place, her daughter was in attendance.

As for the student who was open at school but not at home, I spoke with him after he graduated. He confided: “I remember the teens who talked to us at the Day of Action. It was the first time I heard that I was lucky to be gay. From that moment on, I realized that being gay wasn’t a curse and that I would be OK.”

He is OK. And he has promised to return as a speaker for Green Acres Day of Action.