Reform vs. Scapegoating

Examining Proposals for Improving MPS

For public officials and mass media in Wisconsin, criticizing the Milwaukee Public Schools has become almost as popular as criticizing welfare.

Such criticism has struck a responsive chord among many people. For some, controlling property taxes in recessionary times is the top concern, regardless of negative effects on children’s education. Direct experience with the public schools has convinced others that major changes are essential.

Criticizing MPS is not the problem; this newspaper has never been shy about criticizing MPS. What is disturbing is the lack of analysis behind many of the current criticisms and the potential dangers in several of the proposed “solutions.”

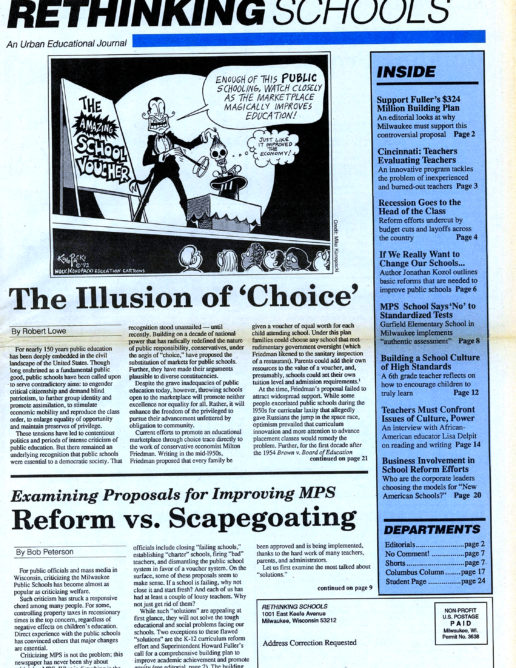

The main “solutions” posed by public officials include closing “failing schools,” establishing “charter” schools, firing “bad” teachers, and dismantling the public school system in favor of a voucher system. On the surface, some of these proposals seem to make sense. If a school is failing, why not close it and start fresh? And each of us has had at least a couple of lousy teachers. Why not just get rid of them?

While such “solutions” are appealing at first glance, they will not solve the tough educational and social problems facing our schools. Two exceptions to these flawed “solutions” are the K-12 curriculum reform effort and Superintendent Howard Fuller’s call for a comprehensive building plan to improve academic achievement and promote equity (see editorial, page 2). The building plan is a worthwhile, desperately needed proposal that deserves support from all sections of the community. The K-12 curriculum reform, meanwhile, has already been approved and is being implemented, thanks to the hard work of many teachers, parents, and administrators.

Let us first examine the most talked about “solutions.”

Closing “Failing” Schools

The Milwaukee School Board decided in January to seek state legislation that would allow the board to close “failing” schools and “to reopen a closed school by contracting with a group or individual to operate a charter school.” While details of the proposed legislation are vague, it is possible that the new charter schools would be privately run, and, in the words of the school board resolution, exempt from “the application of any collective bargaining agreements with respect to reassignment to and teaching conditions at that school.”

Some board members initially supported only the failing-school aspect of the proposal. At a subsequent meeting the board endorsed the charter school concept as well.

This proposal, with its emphasis on charter schools, could possibly begin the abandonment of public schools. Without necessarily examining the root causes behind why some schools are failing, officials might close them down, contract out to private groups, and employ people without regard to their rights as workers, possibly at significantly lower wages.

Several problems emerge.

First, who decides which schools are failing and what constitutes a “failing” school? Will there be an over-emphasis on test scores? Attendance rates? Parent perceptions? While each of these reveals something about a school, over-reliance on any one of them as a determining factor could encourage a variety of frightful practices, from skewing curricula toward standardized tests, to cheating on tests, to crass public relations efforts that have more to do with marketing than education. These, in turn, would be at the expense of the students’ academic achievement.

Second, in addition to asking, “Which schools are failing?” let’s ask: “Why are some schools and many students failing?” “How can we improve education at all our schools?” Such questions would lead to more rigorous analysis.

Third, why must the charter school proposal be couched in the language of abandonment of public schools? The school board motion states that “MPS may grant a leave to any employee who will work at a charter school.” Will this include giving up health care, pension, and salary benefits, as employees currently on leave must do? And while some in the administration deny that they support privatization of schools, why is the administration proposing in current negotiations with the teachers’ union that there be “nothing” in the contract to preclude subcontracting with non-union, private sector, non-certified workers?

Regardless of attempts to build in safeguards, the trend toward privatization could limit who has access to such schools, lessen public accountability and control, lower the wage scales, and worsen the working conditions of its employees. Some might consider such fears extreme. But they are highly plausible, given such national developments as the profit-making, private ventures of entrepreneurs like Chris Whittle, who wants to develop 200 for-profit schools, and former MPS administrator David Bennett, who is establishing “charter” schools.

InnovationPossibleNow

A considerable amount of innovation has taken place in MPS in the last 15 years, although it still represents a small proportion of the total system. Some of this innovation has meant big changes. For example, when the Montessori program was put into MacDowell and Greenfield in the late 1970s, there was a massive change of both staff and operations at the schools.

Similarly, when the African-American Immersion School was set up last year at the old Berger School, the composition and teaching practices of the staff changed significantly. What MPS needs is an affirmative policy of encouraging and offering practical help to citizens and teachers who want to start schools.

For the most part, such changes have been negotiated amicably between the administration and the teachers’ union, setting precedents for how significant change can occur without scrapping collective bargaining agreements. In some cases, teachers are required to have special certification or training, such as in the Montessori, Waldorf, and language immersion programs. In other cases, teachers need to agree to take a certain number of graduate credits in the area of the specialty — African-American studies, the arts, sciences, and so forth. In virtually all specialty schools, a key factor in securing and maintaining quality staff is the high expectations of the staff itself.

To the degree that current labor contracts might inhibit the successful start-up and operation of such innovative public schools, (for example, the controversy that surrounded the staffing of the African-American Immersion School), the administration should come forth with specific proposals and negotiate them with the employee group affected. The employee unions, in turn, while protecting their members’ basic rights should also recognize that certain flexibility is necessary if such innovative schools are going to remain in the public domain.

Another argument in favor of charter schools is that they would release untapped creativity, with teachers and parents working together to design and implement new schools. The current system allows for such creativity. Four years ago, community members and teachers organized the Fratney School. Last September, the African-American Immersion School and the Waldorf School were established, in large part as a result of community and parent organizing. In recent years, the problem hasn’t been the lack of MPS support for such creativity, but the lack of community-based proposals. MPS has opened nearly a dozen new schools in the last five years, and teachers and parents originated only a handful of the new programs. Former Superintendent Peterkin welcomed such proposals, and there is every reason to believe Fuller will also.

An additional argument in favor of the “failing” schools and charter schools proposals is one that is rarely stated publicly — that certain MPS high schools just aren’t working. It’s undeniable that some schools have serious problems. It is possible, however, that radical changes could be made under current statutes and contracts. For example, small innovative high schools such as Central Park East in New York City, working within the philosophy of the Coalition of Essential Schools, have shown that the impersonality of the huge high school and the inertia of some of the staff can be overcome by breaking up large schools into small ones (several within one building) and radically restructuring the curricula and school organization. Such approaches could go a long way toward improving certain Milwaukee high schools, and could be implemented without throwing out the contract between the administration and the teachers’ union.

Vouchers

The “charter” proposal has been put forward in the context of growing calls for vouchers as an alternative to public education. In Milwaukee, Mayor John Norquist has demanded that the public education system be “scrapped” and “replaced with a new system — essentially a voucher or choice system.” Writing in the premier edition of the magazine, WI:Wisconsin Interest, published by the conservative Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, Norquist wrote that he “doubt[s] the current system of urban education can be reformed.” Norquist first outlined this position two years ago, but the timing of his renewed attack couldn’t have been worse. Superintendent Fuller had come on board only six months earlier and had just put his administration team together. The mayor’s attack, combined with his refusal to support Fuller’s request for $35 million to build a desperately needed middle and elementary school, and his denunciation of Fuller’s larger facilities plan, indicate the he is not serious about supporting Fuller’s reform efforts.

Norquist claims that under his choice system, “schools that fail to keep kids in schools, or teach them well, will either go out of business — teachers, principal, administrator and all — or change their ways.” He offers no evidence this would happen. One could imagine that instead of improving the academic program, a school might spend time and money on marketing itself, or create non-academic programs such as after-school recreation that would attract parents but have little to do with quality education. David Reimer, a top mayoral aide and staunch proponent of school choice, has said that school choice would work just as effectively as “choice” has worked in health care. Given that 25% of inner city residents have no health insurance compared to 5% to 10% of suburbanites, such statements are not very reassuring. As analyzed elsewhere in this issue (see article on School Choice, page 1), such voucher proposals most likely will increase inequity without enhancing academic achievement.

Local agendas to subvert public education are getting national support as well, from conservative private foundations and from the Bush administration. Bush, for example, has proposed that $500 million be put into school choice plans that include private schools. The Bush-initiated New American Schools Development Corporation, meanwhile, represents a deepening of U.S. corporate support for private school ventures (see article on business involvement in school reform, page 20).

Firing “Bad” Teachers

In addition to attacking “bad” schools, much has been said about “bad” teachers. Personal experience tells us that struggling, burned-out, even “incompetent” teachers exist — just as in all areas of business and government. Yet some, such as Ed Hinshaw in a week-long series of editorials on WTMJ TV and radio, have turned the attack on “bad” teachers into scapegoating.

In the haste to blame “bad” teachers for our school’s current problems, there has been little analysis of why such teachers exist and why they haven’t been helped or counseled out of teaching. Equally unfortunate, teachers’ unions generally have failed to acknowledge their own responsibility to deal with failing teachers.

Likewise, some teachers tend to blame school problems on the students or their families.

The problem of failing teachers is deeply ingrained in the fabric of our schools. First, there are few structures to assist either new teachers or teachers experiencing difficulty. Teaching is one of the few professions in which there is virtually no on-the-job training once a person starts working. In many teaching positions, particularly in elementary schools, there is almost no chance to confer or collaborate with other adults during the work day. In addition, overcrowded conditions and inadequate social services exacerbate classroom problems, making teaching a highly stressful occupation.

The way MPS teachers are evaluated, or rather not evaluated, is equally problematic. For example, Mike Langyel, the president of the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association (MTEA), has taught for over 15 years in MPS. He has stated publicly that he has never been meaningfully evaluated (principals have never spent more than 15 minutes a year in his classroom), even though the contract mandates such evaluation by building principals.

Some principals evaluate teachers without ever visiting the teachers’ rooms. Other principals fail to intervene with teachers who are in trouble and give such teachers a choice between leaving voluntarily with a satisfactory evaluation or being recommended for dismissal. Most teachers and principals prefer the voluntary transfer. As a result, such teachers might accumulate years of satisfactory evaluations, which can be used in their defense if they are ever confronted by a principal willing to take them through the entire dismissal process.

Principals say they have little time for evaluations, or that the process is so complicated it encourages the transfer of teachers with problems to other schools. Clearly, improvement in the area of teacher evaluation is necessary.

A Deeper Analysis and Real Solutions

Scapegoating leads nowhere. Educators shouldn’t blame students and their families any more than local officials should blame teachers or specific schools. This is not to say these important constituencies have no responsibility to improve schools. They do. And teachers, students, and parents are key players in the equation for successful schooling. But recognizing responsibility does not mean we should collapse our analysis into 30-second “sound-bites” meant solely for television, as some politicians tend to do.

Schools, children, and young people face complex problems. Simplistic solutions that deny how the problems are connected will fail.

No single reform can be “the answer.” Implementing the K-12 curriculum reform, for example, won’t succeed unless we change how we assess students. But neither curricular reform nor improved assessment is likely to happen unless class size is reduced, particularly in the early grades.

And lowering class size requires building new schools and renovating old ones.

Lowering class size, in turn, will not increase student achievement unless teachers have high expectations for all students and change ineffective teaching methods. Similarly, neither teaching practices nor attitudes will change without increasing the quantity and quality of staff development and planning time. And changing attitudes among staff and students necessitates more parental involvement. But to get more parent involvement requires resources and parent organizers at the local school level. Finally, to ensure that students come to school “ready” to learn requires more jobs at decent wages and improved social services in housing, health, and child care.

While the complexity of school reform is daunting, it should not immobilize us.

Instead of wasting our time on scapegoating, we should tackle the hard work of a comprehensive and multifaceted reform agenda.

Such an agenda must be premised on the understanding that effective school reform involves changes both in schools and in the community. Educational issues include what is taught and how, parental involvement, the quality of teachers and principals, school organization, the buildings, resources, and discipline. Broader community issues include decent paying jobs, housing, health care, child care, and recreational programs for youth.

Recognizing the need for a comprehensive reform agenda doesn’t mean we must wait until we can implement it all. Given the economic and political climate, such an approach would leave us paralyzed. What we must do is set short-and long-term goals for our schools and for social services for our children, prioritize immediate needs, and take steps so that long-term solutions become a reality.

Let us first turn to the schools and then to the broader community.

Teachers of Color

A key link to successful schools is the staff, particularly teachers and building principals. Several reforms are needed.

First, the racial composition of the staff must change. Currently, only 17.9% of MPS teachers are African American, even though 57.2% of the students are. There are only a small number of Latino, Asian, and Native American teachers (3.9%), even though children of color make up 72.7% of MPS students. Of the 1,125 new teachers hired by MPS between 1986 and 1989, only 16% were minority, according to the UW-Whitewater Teacher Supply and Demand Project. This resulted in a decline in the percentage of minority teachers. According to one calculation, 26% of MPS students go through elementary school never having a teacher of color, and another 40% have only one.

Increasing the number of teachers of color would have several effects. First, it would ensure that all children are taught by people of a variety of ethnicities and races, including their own. Second, it might also increase parental involvement. Parents might feel more comfortable and more connected to their children’s school if more staff were of the same race or spoke the same language. Third, it would improve the multicultural character of the curricula and staff training, because teachers’ personal experiences play a large role in their teaching.

Langyel, the union president, has proposed organizing a coalition to help double the number of teachers of color by the year 2001. This goal should be supported by all sectors of our community — particularly by local teacher training institutions such as UWM, and the MPS school board and administration, which have inadequately recruited and retained teachers of color.

Teacher Support

Teacher support and development needs to be dramatically improved for new teachers, veteran teachers, and teachers with serious problems.

New teachers need to be mentored and coached, rather than faced with a sink-or-swim option. Veteran teachers who help new teachers need to have time so that such assistance is not just squeezed into the last few minutes before the bell rings. The Mentor Program, started this January, is a beginning, but needs to be strengthened and expanded if it is going to reach all teachers who need help.

Further, the school calendar and school day must be restructured so more time is set aside for staff development and collaborative planning — both before the school year begins and during the school year. Milwaukee allows only two days when teachers can train and work together without students present: one day before the start of the school year and another during the year.

Unfortunately, State Superintendent of Schools Herbert Grover rejected a joint MTEA-MPS proposal last fall under which students would be released half a day early once a month so teachers could plan together. The proposal is sound, however, and should be revived.

For elementary classroom teachers, planning time could be significantly increased if the number of art, music, and physical education teachers were doubled. This would also give students more instruction time in these areas.

Inservice and training must also address the issue of teacher attitudes toward children — specifically the race, class, and gender bias of some teachers. Such attitudes result in low expectations toward certain students, undercutting the students’ chances of success.

Smaller Schools and Classes

Many schools are too large, and this promotes impersonal and unsafe conditions. The school board should adopt new policies limiting the size of schools and consider placing several school programs within one building.

Further, too many classrooms are overcrowded. In the 1990-91 school year, 26% of the elementary classrooms had 30 or more students, according to MPS figures.

This contrasts to an average class size of 22 students in many Milwaukee suburban schools. When class sizes are smaller, teacher-student contact is increased, individualized teaching is more likely, student and teacher attitudes improve, discipline problems diminish, teacher stress decreases, and teachers are more likely to be innovative.

Teacher Evaluation

The union has been accused of protecting “bad” teachers and the administration has proposed changes in evaluation procedures. As with other problems, the issue is not as simple as it first appears. It involves academic freedom and due process, the nature of evaluation procedures, and the competence of the evaluators.

Teachers, like all employees, deserve due process in disciplinary procedures. They also need protections from supervisors or principals who may base evaluations on non-teaching matters, such as political beliefs, race, gender, or union activity. At the same time, students and parents deserve competent teachers. Herein lies the importance of having quality principals who are willing and have the time to make meaningful evaluations.

The issue is also linked to the need to retain good teachers and to help veteran teachers experiencing difficulties. MPS, like most school districts, can provide this much needed support. Programs such as peer coaching (when two classroom teachers learn from one another) or peer evaluation (when “lead” teachers are involved in evaluation) should be considered (See article on Cincinnati peer evaluation, p. 3).

Staffing

Perhaps the most persistent criticism of the teachers’ contract is that it restricts staffing decisions at schools. Current provisions usually follow straight seniority and have been criticized for conflicting with a school’s ability to get teachers in agreement with its educational philosophy or focus. Spence Korte, principal at Hi-Mount Elementary School, has suggested that a committee of exemplary teachers, selected by other teachers, both hire new teachers and mentor current ones. In other districts seniority is only one element in staffing decisions. For example, a committee might interview and hire from a pool of three veteran teachers, rather than merely taking the teacher with the most seniority.

It would be good for all parties involved to examine staffing practices such as the use of school-based committees of teachers being involved in staff selection, and their effects in other districts. This might better ensure that incoming teachers agree with the school’s vision. Those defending the rights of teachers should be far-sighted enough to take risks in such matters, while not giving up rights to a management that has repeatedly demonstrated its incompetence. Union advocates must accept responsibilities that, although initially uncomfortable, are necessary for school reform.

At the same time, the administration should not view teachers as assembly-line workers and speak of “management’s prerogative” to “move around human resources” at whim. In current contract negotiations, the administration has proposed eliminating all seniority. It has proposed, for example, that principals be able to transfer any teacher at the semester. The only recourse the teacher would have is an appeal to the Executive Director of Human Resource Services, whose decision would be final.

Eliminating seniority completely would be a disaster, subjecting teachers to the caprice of principals and administrators, removing any sense of job security, and making it virtually impossible to attract and retain quality teachers to MPS. It would also open up the system to abuses of favoritism and patronage, with teachers potentially being transferred because of race, gender, political beliefs, or union and community activism.

The administration needs to put forth feasible and well-thought out proposals if they expect the union to respond in a flexible manner.

Principals

Research shows that successful schools often have principals who act as “educational leaders.” Aside from being good administrators, principals should be outstanding classroom teachers and should be capable of motivating and working collaboratively with staff and parents.

Fuller’s administration is putting much more pressure on principals than previous administrations and has prioritized the development of a Principal Leadership Academy. Unfortunately, when “problem” principals are identified in MPS they are often transferred to another school. Or they may be sent temporarily to Central Office, later returning to a school as an assistant principal.

Improvements need to be made in the hiring, training, evaluation, and dismissal of principals. A career in school administration should not be a cushy alternative to classroom teaching; poor teachers usually make poor administrators. Teachers and parents should have some input into principal evaluations.

Quality control needs to be tightened when hiring principals. Principals, for instance, should agree with and have a background in the pedagogical focus of the school. This could be ensured if teachers were involved in the hiring process of a principal for their school. Some School-Based Management schools already have instituted such a practice successfully.

In addition, principals and Central Office administrators should be required to experience the day-to-day life of teachers. For principals, this should mean continuous teaching responsibilities: at the secondary level, this could take the form of teaching one class; at the elementary level, it could mean teaching a reading group. For Central Office administrators, it could mean a semester-or year-long “teaching sabbatical” once every five years.

Learning Environment

Improving the classroom learning environment is just as important and goes hand-in-hand with improving the quality of the staff. Our schools and classrooms must become communities of learners, with a common vision and shared respect for what is being learned. There must also be quality one-to-one relationships between students and adults. Some of the most successful schools in Milwaukee have a common focus and vision, although virtually all are still struggling to build quality one-to-one relationships. Common school visions vary from pedagogical perspectives (Montessori, Open Education) to language emphasis (the language immersion schools) to emphases such as the arts, the environment, computers, and math and science.

A common vision focuses staff energies and builds expectations among parents, teachers, and students. MPS should require all schools to develop such a vision and to give staff time to do so in consultation with parents.

Even with reforms such as smaller classes and a common vision, schools need to improve the content and methods of teaching. The K-12 curriculum reform effort (see Rethinking Schools, Vol. 6 No. 1), combined with reforms in assessment, is the key link in improving academic achievement. Both Superintendent Fuller and the school board have played important roles in supporting this reform.

Implementing the 10 learning goals and their performance indicators in the new K-12 curriculum has the potential to dramatically improve education. Since September, the K-12 process has already increased the quality of staff development programs, and provided dialogue and collaboration among teachers and schools. The reform’s ultimate success, however, depends on leadership both by the administration and the teachers’ union, and on structural changes such as smaller classes and more teacher planning time.

The issue of student discipline and attitudes is also important. Superintendent Fuller’s new strict policies have helped, but student resistance to learning will only be overcome with additional measures such as making our curriculum more activity-based and student-centered. In addition, there needs to be substantial increases in social services for students, specifically social workers, psychologists, and guidance counselors.

Parent Involvement

Parent involvement at school and at home is a key factor in a student’s academic success. MPS policy goals recognize that “parent and community members will become significantly more involved in the achievement of MPS’s vision, goals and objectives.” And this means more than pizza fund-raisers. At the heart of the issue are regular parent contact with classroom teachers, and parental involvement in committees with power to affect school policy and curricula.

Unfortunately, talk is cheap. Schools must ensure that structures such as school-based management councils truly give parents significant influence in school matters. Parents should not only feel welcome in schools, but should be encouraged to volunteer in classrooms or other school activities.

Most important, MPS as a system must change the overly bureaucratic ways in which it encourages parental involvement. While a parent involvement office at Central Office has an important role, parent organizers need to be school-based. A few schools, such as Kosciuszko Middle School, have parent organizers. Based on their success, the school board should allocate funds for hiring organizers at many more schools.

Facilities

If all goes according to Superintendent Fuller’s plan, Milwaukee voters will decide in April 1993 if they support a $324 million building and renovation project for the city’s aging schools (see Rethinking Schools, Vol. 6, No. 2). The administration and school board are finalizing recommendations on the building plan, whose main purpose is improving academic achievement in MPS and ensuring equity between MPS and suburban schools.

Overcrowding leads not only to large class sizes but to conditions in which children are taught in coat rooms, supply closets, and hallways. In addition, many elementary schools lack art and music rooms and have inadequate libraries.

Public opposition to the building plan is being spearheaded by Mayor John Norquist. This must be challenged by a broad coalition of concerned citizens who understand the importance of putting our children ahead of election year politicking and Reaganesque economics (See editorial, page 2).

Community Problems

Change in the community is equally important. Schools are not isolated islands but rather microcosms of society.

Two matters must be kept in mind when discussing schools and communities. First, regardless of the non-school problems facing our children and families, educators cannot use such problems as an excuse for children’s lack of academic success. Given the amount of time children spend in schools, we should be able to do a better job than we are.

Second, improving our schools must be in the context of renewing the entire community, economically as well as culturally.

A change in specific social policies could significantly improve life in our city and schools. The most obvious example is the impact of racism and poverty on housing segregation in the metropolitan area.

Milwaukee is the most segregated metropolitan area in the nation, with 89% of all African-Americans in the area living in the city proper, according to 1990 census figures as reported in The Milwaukee Journal. Important factors in this segregation are the city’s long-standing refusal to build low-income housing in outlying areas of the city, the refusal by most suburbs to build any low-income housing, and the discriminatory practices of banks and real estate companies. Because of housing segregation, efforts at school desegregation have been very costly. Given the strength of racism in our society, governmental leaders have been unnecessarily timid in choosing the best way to foster desegregation. They failed to mandate a busing plan that would have paired and clustered schools (see Rethinking Schools, Vol. 1, No. 3). This could have equalized the burden of busing between the races and reduced the cost of busing substantially.

Other societal problems also affect schools. Consider the economic depression that exists in parts of Milwaukee. Between 1979 and 1987, corporations moved more than 51,150 manufacturing jobs out of the four-country metropolitan area. This has particularly affected African-Americans, and the unemployment rate for blacks in Milwaukee is officially 16.6%, or 5.5 times that for whites. While some new jobs have been generated, 96% of them are in the low-paying service and retail sector and have few benefits, according to the Social Development Commission’s (SDC) report, Crisis of the Working Poor. Youth see that a high school diploma no longer opens doors to high-paying union jobs at factories like A. O. Smith. Thus the incentive to stay in school lessens.

Another result of this depression has been a massive increase in poverty for Milwaukee children. In 1970, about 15% of MPS students were eligible for the federal free-lunch program. Today, 58% of the students qualify. It is projected that by the end of the decade, two-thirds of all children will live in poverty.

Such poverty also causes problems in the areas of housing, health care, child care, nutrition, and crime. Housing is particularly troublesome. The SDC report documented that the availability of low-income housing in Milwaukee has declined in the last two decades. As of 1985, there were 64,300 low-income households, but only 52,100 low-cost housing units. Unable to obtain jobs with salaries that can sustain a family, many families must move frequently and double up in living quarters with relatives. This means that many schools in Milwaukee have a high student mobility rate.

During a single school year, many students will leave a school, and many more will enter. This prevents coherent and consistent instruction for these children. For some children, living in cramped quarters means there is little quiet space to do homework.

Health problems also affect school performance. Whether it’s lead poisoning, malnutrition, increased absenteeism due to illness, or serious health problems due to inadequate pre-natal and post-natal care, children’s performance at school suffers. SDC estimates that there are 49,000 households in Milwaukee County without health insurance.

The number of children born with special needs associated with low birth weight has also increased. These children often require special services. According to statistics gathered by Houlihan and Associates, consultants for MPS, low-birthweight infants comprised 8.7% of total live births in 1986 in Milwaukee. The figure increased to 10.1% in 1988. Such trends constitute one factor in the growing number of students with exceptional education needs. Due in part to the increase in the number of exceptional education students — who need additional classrooms, specially trained teachers, and more individual attention from regular classroom teachers — art and music rooms at many schools are lost.

The lack of decent jobs means that people have to work more to make ends meet, sometimes taking on two jobs. As a result, children get less attention from adults and are at times left unsupervised because of a lack of affordable daycare. The Wisconsin Child Care Improvement Project found that 293,609 children in the state needed day care while their parents worked, but only 80,906 spaces in licensed groups and family settings were available. So, television becomes the baby-sitter, and children enter first grade who, on the average, have watched over 5,000 hours of television.

That’s more hours than the average person spends talking to their parents in his or her entire life and more time than is needed to get a graduate degree.

The increase in poverty has been complemented by an increase in crime and child abuse and neglect and a decrease in recreational opportunities for many inner city youth. Given social and economic realities, adolescents are tempted to turn to gangs for identity and security and to selling drugs for employment. Mayor Norquist’s claim, in the Milwaukee Sentinel this January, that poverty doesn’t cause crime, but “crime causes poverty” is an insult to our community.

Conclusion

Our society’s educational problems will not be solved overnight. We need to address both educational and social issues if we are to create a community that can raise healthy and productive children.

Educationally, several initiatives must simultaneously move forward with political and financial support at the local, state, and federal levels. At the very least, the following should be supported:

- A plan to double the number of teachers of color by 2001.

- The $324 million facilities plan and referendum, proposed by Superintendent Fuller, to build new schools and renovate old ones.

- Full implementation of the K-12 curriculum reform, including performance-based assessment, so that all students can learn to their fullest potential.

- Changes in how teachers and principals are hired, trained, and evaluated. The teachers’ union, administrators’ council, and MPS should revamp their inservice training and evaluation pratices so that teachers and principals can improve their skills.

- Changes in the financing of public schools so that there is equity between the amount spent on children whether they live in poor or rich communities, and so school funding increasingly relies on progressive taxes such as the income tax. MPS recommendations to change the state aid formula should be supported.

- The Campaign for New Priorities, initiated by the National Education Association and others, so that the military budget is reduced by 50% and the money is invested in social services, infrastructure, and our communities.

- Social reform initiatives, specifically of programs and policies that promote family-supportable jobs, adequate housing, childcare, health, and recreation for all of our population.

Some people may dismiss these proposals as idealistic and too expensive. Others will disregard them as too complicated and will continue with simplistic formulations or scapegoating. If that is the case, and the Milwaukee community fails to seriously address school reform, the prognosis is poor for not only quality public education for all, but for the health of the city as a whole.

If, on the other hand, government, business, and community leaders recognize that the future of our children is, in essence, the future of our city, there is hope. In the months ahead, we must nurture the hope that exists, engage in on-going discussion and coalition building, and strive to create a powerful political force to turn this city around.