Rats

Students take action to defend their classroom pets

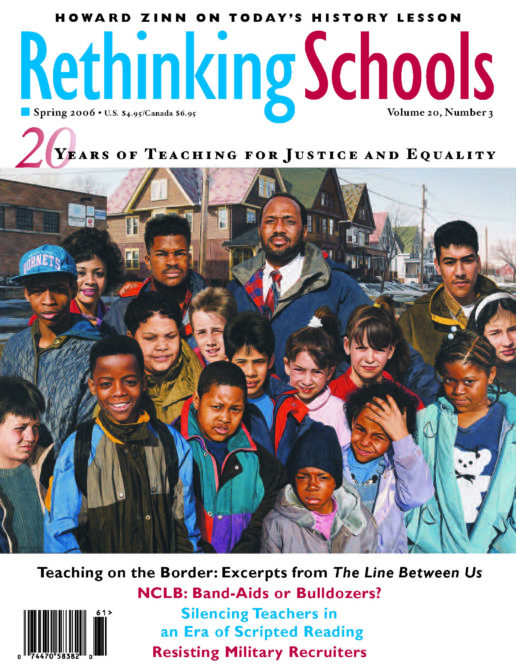

Illustrator: Kate Lyman

Maggie* stepped up to the podium, clutching her friend Isa’s arm. Looking up at the seven school board members on the stage, she spoke into the microphone. “My name is Maggie and I’m going to share a letter that I wrote.”

My name is Maggie and I think we should have pets. We already have two rats, Templeton and Max. They are my best friends and they could help kids all over Madison Metropolitan School District. We have to clean their cage and feed them and give them water in a water bottle. We play with them at quiet reading. If we did not take them from the Humane Society, they would have died. So please don’t take them away from us.

Maggie was one of six of my 2nd- and 3rd-grade students who spoke to the school board in Madison, Wis., that night. Clara came, but backed out. “There’s a million people here,” she said, “I can’t talk in front of all these people!”

The other students were nervous, too, choosing to go up in pairs for support. But I was proud of them for speaking out in that daunting setting, in front of at least a hundred people, including school board members, the superintendent, and the school district lawyer.

It had been an extra challenging year. Due to overcrowding in our school, two classrooms were combined into one room. Additionally, our classroom was an “ESL cluster,” which meant that more than the school’s average (29 percent) of English language learners were assigned to our class. Of our 32 students, 25 spoke a first language other than English — mainly Spanish and Hmong, but also Fulani, Urdu, and Vietnamese — and lacked proficiency in oral and written English.

Because of language, and also because of differing background knowledge, a handful of students dominated classroom discussions. We had had some success in involving the students in a “get out the vote” action, but activities that I had found successful in the past, such as the “Inequality in World Resources” activity from Rethinking Our Classrooms, Volume 1, fell flat.

But the campaign to get our classroom animals back engaged the kids in a direct and relevant way that discussing local, national, or world issues had not.

The Classroom Adopts

Several months before the school board meeting, our class had joined the Humane Society’s “Adopt a Teacher Program,” which allowed classroom teachers to borrow animals that had been surrendered to the shelter. After notifying parents and investigating potential problems with allergies, Richard Wagner, the Humane Society’s education coordinator, came in with the rats to demonstrate proper care and handling.

Initially, not all students were enthusiastic about having rats as classroom companions. “Rats!” said Isa. “Disgusting!” Richard and I explained that these animals were not the same as the rats who become household pests. Domestic, or “fancy rats,” as they are called, are bred to be companion animals. The word “fancy” comes from “fancied” or “liked,” unlike wild rats that are generally despised. Fancy rats can be as smart and as cuddly as dogs or cats. They are also clean, with no offensive odor, as long as their cage is kept clean. They become attached to people and can recognize them by their smell. They can be taught to come to their name and to do tricks. There are even rat clubs, rat newsletters, and rat shows.

In the following days and weeks, I brought the rats out of their cage for short, supervised sessions. The students held the rats in their arms and watched them explore on the student tables. I read daily reading from the book My Pet Rat by Arlene Erlbach, which combines the experiences of a girl who acquires a pet rat with fascinating facts about domestic rats.

Through the reading and discussions related to the book, as well as daily observation and interaction with the rats, the students came to better appreciate and understand them. The students voted to name them Max and Templeton, and once they saw them as individuals, their personalities became clear. While Templeton enjoyed being cuddled and petted by the children, Max was more active and tended to climb and explore. Max and Templeton also seemed to favor the children who handled them calmly and confidently. Both rats would climb up into Mai Nyia’s arms and even hyperactive Max would settle down on Mai Nyia’s fleece sweatshirt.

Max and Templeton inspired students to write. Tim, who hadn’t written more than two sentences that year, worked cooperatively with a partner to write two pages about the rats for our class news. Other students wrote stories in their draft books and illustrated books about the animals. Students argued who would get the privilege of cleaning the rats’ cage. They diligently followed all of Richard’s directions as they added fresh food and water, washed the bottom of the cage, and then added clean layers of newspaper and bedding. They brought in carrots, strawberries, grapes, and other treats for the rats from home and they donated small boxes and paper towel rolls to provide stimulation and variety to the rats’ living quarters.

As new students joined our class, their classmates taught them how to handle and care for the rats. One of my new students, a Hmong girl from a refugee camp in Thailand, entered our class with no previous schooling and no English. She hung back, rarely smiling or even interacting with the other children. No one, not even the Hmong bilingual specialist could get her to open up. But as she held Templeton, a rare smile would creep on her face. She would even laugh as Templeton crawled up on her shoulder and tickled her neck.

A District Mandate

A few months later, when Max and Templeton were well established as important members of our classroom community, we received a call from Richard that the district had ordered him to remove all animals from classrooms by the following Monday. The district was apparently responding to a parent complaint concerning allergies by banning all animals from the schools. The information we received was confusing. Reference was made to a school board policy prohibiting “dogs and other animals” from school premises, a policy contained in a section about playground rules. “Air quality” was cited as a concern and, in some schools, all plants and even the goldfish in the school office had to be removed.

Isa overheard Connie, my teaching partner, and me talking about the mandate. “Maggie, Maggie,” she cried out, rushing over to her friend, “I have really bad news! They’re taking the rats away!” “What? Taking away Max and Templeton?” responded Maggie, and soon everyone had heard.

“We need to tell the principal not to let them take away the rats!” someone said. I tried to explain that it wasn’t the principal’s fault. Quickly I sketched out the hierarchy of the school district, explaining the role of the school board and the superintendent, who is the principal’s “boss.” I told the students that they could tell them their feelings through a letter or email, which many students chose to do the next day.

We didn’t have time to spare, so the next morning we quickly brainstormed reasons to allow animals in the classroom. We talked about what it meant to try to persuade someone to do something, and about a possible format for a persuasive essay. We didn’t spend much time planning or pre-writing, because we only had a few days to try to stop the action. But the students’ voices came out strongly in their writing, perhaps all the more authentic because their comments came from the heart instead from a modeled writing lesson.

Although some students wrote about the educational benefits gained from having animals in the classroom, most of them stressed the emotional impact of the experience. “We want to keep the rats because they are our friends,” wrote Josie. “They help us learn and cool off when we are mad. And they love us as much as we love them!”

“I think it’s not fair because what if you needed an animal to do science and also what if you needed a friend?” asked Carmen. “I think if somebody was doing the same thing to you, you would be feeling sad. Why don’t you first think about it?”

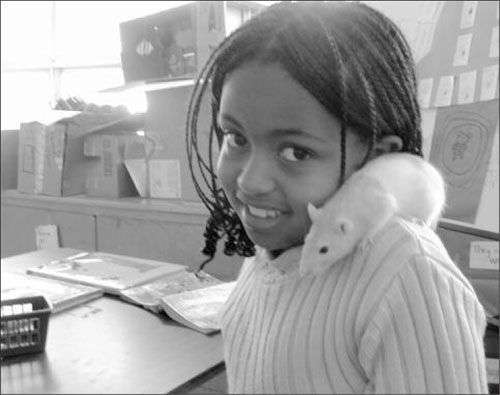

The students practiced a lot of writing skills in those few days. They edited their letters, typed them on the computer, and learned how to send them via email to the school board members and superintendent. Maggie suggested they send letters to the local newspaper. The Capital Times published four of their letters the following week, along with a photograph of Mai Nyia holding the rats in her arms. “Hawthorne Pupils: Let Us Keep Our Rats!” was the headline.

After reading the letters to the editor, a producer from Wisconsin Public Television contacted me to see if he could include my classroom in a program they were developing called “Democracy it is!” The program featured elementary students working through the system to create change. I asked my students, who agreed that this was an exciting prospect, and then asked my principal if we could have the rats back for a day for the filming. She forwarded my request to the assistant superintendent, who granted my request, but only if I received permission from all the parents (which I had intended to do) and if I “developed a plan that notes how much instructional time will be used and how the activities will relate to curriculum standards.” I stayed late that night annotating all the relevant standards — 14 social studies standards, six science standards and the entire section on writing in our 2nd- and 3rd-grade language arts standards.

All but one of the parents granted permission for the filming, but several students, particularly three Hmong girls were reluctant. Mai Nyia, Lisa, and Pa told me that they didn’t want to say anything. I assured them that they wouldn’t have to be interviewed or participate in anything but the large-group filming. I was surprised, given the reluctance of so many of my students to speak up in class discussions, how many of them did volunteer to read their letters in front of the camera. Mai Nyia, Lisa, and Pa, who hadn’t chosen initially to write a letter to the school board decided to get to work. They proudly showed me their essays. “Did you want to read them in front of the camera?” I asked. They looked at each other and said, “Yes!” Hand in hand, they went over to the cameraman and read their letters.

Student Role Play

Since some students had indicated interest in reading their letters at the school board meeting, I decided to stage a role play in which students would debate the issues as school board members. I realized that we hadn’t spent much time talking about why school board members might be opposed to having animals in the classroom, so I asked the students to help me generate a list of pros and cons. Since none of my students had allergies to the rats, they could not understand why the allergy issue might be such an important issue. When we first got the rats, Clara said that her eyes were tearing when she was near their cage. I moved Clara’s table place to a spot farther from the rats and asked her daily how she felt. At first she didn’t hold the rats, but after a while her eyes stopped watering and she was able to hold the rats without a reaction. Either she got accustomed to their presence or she’d had a cold, not an allergy. If anyone in the classroom had allergies, I would have asked another teacher to take the rats or I would have sent them back to the Humane Society. The following are the lists the students generated:

Reasons we should have animals in our classroom

They are like friends to us.

We use them to learn about science.

They might help you calm down.

If you don’t have a friend they might be your friend.

If you’re sad they can help you cheer up.

If you have no one to play with, you could play with them.

When we’re lonely we need friends.

Children like pets because they are fun.

Rats are good pets.

You learn about the animal and then you won’t be scared of them,

You learned how to clean their cages, give them food, water and take care of them.

Maybe because you need friends.

If you are being bullied by someone, they will make you feel better.

You might not be scared of them.

They don’t have owners.

Reasons you might not want animals in the classroom

They might chew on something that is near their cage.

Kids might be allergic to them.

Kids might not like them.

You might not concentrate on your math.

You might be scared of them.

They might eat your homework.

They might bite you.

They might get out of their cage.

They might eat something near their cage and might be poisoned.

They might make a mess.

They might be scared of you.

They might get out and hide somewhere, like in the cubbies.

Predictably, given their passion about their classroom pets, the group quickly came to a consensus. Maggie, the one “school board member” who held out on her “no animals” position, quickly relented. “Oh, all right, you convinced me. They can have their animals back.” The class cheered.

The role play was valuable. It was a start, at least, at presenting an opposing point of view — a task that was difficult for my students, given their joy at sharing their classroom with animals and their sadness at having to see them go.

Benefits of Animal Visitors

Throughout my teaching career, I’ve had many different animals visit the classroom, including guinea pigs, gerbils, snakes, frogs, cockatiels, chickens, and guests with guide dogs. Each animal has inspired children in ways that boxed curriculum rarely does.

Beyond the opportunities for making science, social studies, math, and language arts connections, the animals help students who are struggling emotionally. I remember Daniel, a new arrival from Mexico. He had little previous education, would not try to read or write, even in Spanish, and was having trouble connecting with the other kids. He would pull his sweatshirt hood down over his face and crawl under a table. After weeks of making little progress, it was the experience of watching chicks hatch, caring for them, and observing them that helped him come out of his shell. Soon he was attempting his first writing about the “pollitos” and showing his drawings of the chicks to other students.

Time after time, I have seen angry, disconnected students let go of their bad morning or their recess conflicts when I redirected them to care for animals. For some kids, caring for and about animals is a first step in leaning to feel and show compassion for their classmates. Caring for animals also is a big step toward developing a classroom community. With an animal in the room, the focus shifts from “me” or “me and my friends” to the group.

Although I realize some people can have serious allergic reactions to certain animals, I also do not understand why what is a problem for a few children has to result in banning an experience that is so important for many others. I happen to have fairly severe allergies to cats and rabbits and would never have an animal in my classroom that was making a student suffer from asthma or allergies.

But in the 28 years that I have been teaching, I have never had to remove an animal because of allergies. Even according to the school board member who most strongly advocated for the ban on animals, he has had “less than a handful” of complaints a year. Far more children get broken limbs at recess (I’ve had two students who broke their legs in the past two years) and bee stings are potentially a far more serious risk to students with allergies, yet we don’t (and shouldn’t) ban recess and field trips.

School board members also argued that students are not safe with animals, either because of the risk of bites or because the students may be fearful. My experience is that children who learn to interact appropriately with animals are much safer than those who don’t. Most of my students live in low-income housing and do not have the opportunity to have pets. They need to be taught safe behavior around them. Particularly in our community, where dogs are often bred for protection and/or trained improperly, dogs can pose a serious threat to children. A few years ago, I was taking a neighborhood walk with my class when a stray dog came up to them.

They started to scream and run from the dog, behaviors that had the dog been aggressive or skittish, could have resulted in a bite. I invited the education director at the Humane Society to come in with her dog and teach them how to interact safely with a dog. We all practiced “standing like a tree” as her dog came up to the children and sniffed them.

Unfortunately, the students did not succeed in getting the animals back, at least not that school year. A committee was formed to make a recommendation on whether or not, and under what circumstances we will be allowed to have animals in the classroom.

But my students found their voices. They learned, through writing and speaking up publicly about an issue that is important to them, that they can have an impact. Even if the school board denies their pleas, they saw their letters published in the paper and became part of a public TV production. And they were inspired to speak up on other issues. After we read a Time for Kids article about how global warming is endangering the arctic habitat of penguins and polar bears, they immediately wanted to take action. “We can write letters to the president, like we did when we wrote to the school board about the rats,” suggested Maggie. We talked again about persuasive writing, and about whom they wanted to address in their letters. Some wanted to write the mayor about local factory pollution. Some kids wanted to make signs for their neighborhood telling people to carpool or ride their bikes to cut down on gas emissions. The second time around, the letters were a bit more polished, the arguments more persuasive.

And this time, everybody participated in the writing. The kids edited and typed their letters, addressed their letters, and mailed them in the mailbox down the street.

In response to the students’ interest in habitat destruction of penguins and polar bears, we also decided to do an endangered animals unit. Students chose an endangered animal to research and write about. They also presented their knowledge to the class in the form of a play, puppet show, game, or poster. Then, after reading an article in Kind News, the students became interested in puppy mills (businesses that abuse and exploit dogs, keeping them confined for breeding purposes and then ship puppies to pet stores to be sold for large profits). Further research and then social action relating to this issue would have been the logical next step; however, we needed to finish up projects and portfolios and complete end-of-the-year assessments.

Almost every day after the rats left the classroom, Mai Nyia came up to me and said, “Kate, I really miss the rats.” I miss them, too, but I am thankful to them for helping my students learn to care for other living things. I’m thankful, too, for what the rats taught me. They reminded me to be patient with my students. They reminded me that it is often the issues closer to home that spark an interest in social action. The students’ experiences advocating for the rats gave them the confidence to raise their voices to speak out and protest policies they found unfair. The rats were only the beginning of a thread of animal advocacy that wove through the entire school year.

Epilogue: Now it is more than a year after Maggie spoke at that school board meeting. The committee met several times during the first semester. I was invited — along with several other teachers who had advocated for animals in the classroom — to attend two meetings.

We were able to speak at the meetings, but none of our suggestions were incorporated in a proposal that banned virtually all animals from the schools. (The exceptions were guide dogs, certain insects, and goldfish.) The proposal was presented to the school board on Jan. 18, 2006, with surprising results.

The board members voted unanimously to reject the proposal and instructed the committee to reconvene and come up with guidelines that would, indeed, allow for animals in the classroom. I would like to consider this decision a victory, but the real momentum behind the board’s change of heart may have been that the board’s anti-animal stance had made it the laughing stock of talk-radio commentators. The board also voted 5-1 that, while the committee is working on a new proposal, all animals previously in classrooms can return. Unfortunately for us, Max and Templeton have been placed elsewhere. But I am looking forward to some new animal guests. The students who were 2nd graders in my class last year still talk about their experience with the rats and write stories and poems about them.

*All students’ names have been changed.