Raising Money, Raising Consciousness

Alternative fund-raising companies bring new ideas to an old-school business

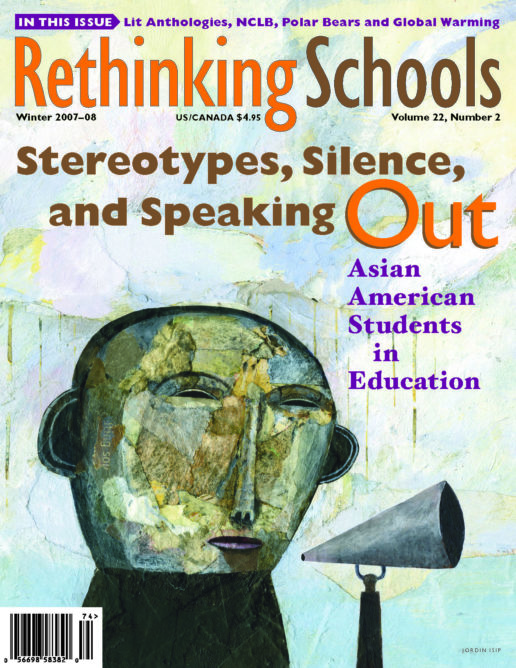

Illustrator: Chris Mullen

My daughter came home from her third week of kindergarten and announced that her entire school had met that afternoon, “Even the big kids.”

It was her first all-school assembly. I fantasized about team-building projects-planting trees together, a school-wide mural, a dance party. Instead, she pulled a glossy catalog out of her little purple backpack, tapped its cover and said, “If we sell enough stuff, we can have an ice cream party.”

Welcome, my dear girl, to Fund-Raising 101.

The school fund-raiser is a rite of passage in American schools. Kick-off assemblies, such as the one my daughter sat through, are repeated nationwide, as a representative from a company comes and tries to turn a group of kids into excited, competitive purveyors of plastics and sugars by dangling a cheap award in front them. Think Alec Baldwin and the oft-promised knife set in Glengarry Glen Ross.

The whole thing is maddening on multiple levels. First off, there’s the junk most of us don’t want as we try, per Oprah and Rachel Ray’s advice, to de-clutter our homes. My daughter’s QSP/Reader’s Digest catalog offered a Harley Davidson mug, an apple candle jar, and a jewelry cleaning kit, as well as the ubiquitous wrapping paper and chocolate.

Plus, as my fantasies suggest, we want to believe that in addition to writing and arithmetic, our kids will be exposed to enriching, challenging experiences at school. In the current standardized-testing environment, principals and teachers tell us how tough this is, as every minute of instruction time counts. I’ve seen several creative programs not explicitly tied to a core (e.g., testable) subject rejected by schools because of this argument. However, there is time for a man in a company-logo polo shirt to spend 30 minutes with my daughter and her classmates and rev them up about selling “The World’s Finest Chocolate!” (When I attended this year’s fund-raiser, he had all 300 kids repeating this phrase before tossing out candies to the audience.)

Fund-raising is big business, and schools rely on it because they desperately need the bucks. According to the 650-member Association of Fund-Raising Distributors, schools and other nonprofits garner about $2 billion every year by selling products. However, short of the Pentagon throwing a bake sale for public schools, per that old liberal bumper sticker, is there another way for schools to find the money for new playground equipment, field trips, and band uniforms?

More alternatives to traditional fund-raising are sprouting up as parents become frustrated by the hypocrisy involved in fund-raising-teaching kids to eat healthfully and then sending them out to sell foods full of trans fats and high fructose corn syrup, or encouraging them to be gentle on the earth and then giving them catalogs full of plastic items. After tossing our catalog last winter, I discovered a groundswell of do-it-yourself fund-raisers via the Internet, including schools that have partnered with local farmers to sell jam, honey, cheese, and fresh produce. These campaigns not only allow parents, grandparents, and neighbors, the “usual suspects” of the school fund-raiser, to feel connected to the products they purchase, but also provide curricular opportunities for kids to meet the farmers and learn firsthand about what they’ll be selling.

Such homespun efforts are wonderful but time consuming. A similar but more large-scale and ready-made option comes from Equal Exchange, the first and largest fair trade, for-profit organization in the United States. The worker-owned cooperative recently created a fund-raising program that is emerging as one of the better-organized alternatives to the powerhouse fund-raising companies like QSP/Reader’s Digest. Its products-coffee, tea, chocolate, cocoa, nuts, and dried fruit-lend themselves to fund-raising, and the company has a proven track record as an ethical business.

Virginia Berman, who oversees grassroots outreach for Equal Exchange, said that their customers got them thinking about alternative fund-raising. The cooperative has a long-standing wholesale program for faith-based organizations, through which members of a congregation can buy and sell the cooperative’s products for profit. But increasingly, Berman said, K-12 schools and college groups were coming to them, interested in using Equal Exchange.

Large, fund-raising distributors succeed by offering a well-honed system-a representative who leads the school assembly, the packet with a catalog and order form, and a Web site. They also guarantee a return, usually 40 percent to 50 percent of sales. Equal Exchange is trying to guarantee the same, though where the other part of their profit goes is quite a different story. Unlike large, conventional businesses, which have the ultimate goal of maximizing profits, Equal Exchange uses its profits to cover the costs of getting the product from the farmer to the consumer, including a premium to the farmers, educational materials for consumers and farmers, quality control, packaging, and processing. Their profits also go to some less conventional expenses.

“Always, 10 percent of our profits go to charitable giving, and 40 percent gets distributed amongst the 70 worker-owners,” said Berman. “Our salaries are very unconventional but in keeping with our mission: the ratio of the highest-to-lowest paid employee at Equal Exchange is 4-to-1, as compared to a more common ratio of 350-to-1 in a large corporation.”

Ensuring an ethical company is behind a product goes a long way toward convincing parents to use Equal Exchange as a fund-raiser. Yet harried, weary parents also need some assurance that the process will be painless. Berman and her co-workers have created a similar system that mimics some organizational patterns of the bigger fund-raising companies. During their pilot year in 2006-07, 120 organizations used the service, including Parent Teacher Associations, high school bands, and college students focused on human rights issues.

Now the company is taking it a step further by introducing a curriculum that will connect kids to food and raise some of the central questions of the Fair Trade movement. Given that Equal Exchange was built on convictions (their first product in 1986 was coffee from Nicaragua, which was then under an embargo by the Reagan administration), this curricular connection made sense. Geared to elementary and middle school students, the lessons are intended to help students learn more about the places and people involved in growing the products they are selling.

One school that has been working with Equal Exchange from the beginning is the Brooklyn New School (BNS), a K-5 public school in New York City. They had been using a traditional, large-scale fund-raising program, until one parent, Emily Schnee, was so turned off by a plastic Shrek wall clock, she went looking for other options.

When she presented the possibility of using Equal Exchange at BNS, she initially heard plenty of arguments about profit margins and the necessity of an easy system. These were parents who knew how difficult school fund-raising can be, but how crucial the funds are. Schnee’s conviction that fund-raising doesn’t need to be focused on material goods most people don’t want and had likely been made in unfair conditions eventually convinced BNS to give Equal Exchange a try. Three years ago, the school used Equal Exchange alongside their regular program. For the past two years, they’ve used only Equal Exchange.

As Berman noted, it takes an adjustment in school culture to make alternative fund-raisers work. Schools that will most successfully adopt fund-raisers like Equal Exchange’s will be motivated by more than just profit. There needs to be an understanding that the fund-

raiser represents the school’s values and has political-cultural teaching opportunities.

“People get behind the fund-raiser not just because it raises money for their kid’s school,” Nick Bedell, PTA co-chair and BNS parent explained, “but because it is an ethical model for fund-raising.”

Ethical fund-raising. I think of those words as I replay the scene in my daughter’s school gym from a few weeks ago. Prepared to hate every moment of the kickoff, which I’d decided I needed to see for myself, I was mainly taken with how dull it was. The kids were clearly bored. Only the candy and a non sequitur, all-school sing-along of “YMCA” got their attention. Well-trained but unengaged, they raised their hands as the company rep tossed out rhetorical questions: “Does anyone in your house use candles?” “Who likes getting presents wrapped in bright paper?” He never made a clear connection for the kids as to how the money they earned would be spent. No one talked about the products and where they came from. The ethic of having pride in what you sell was nonexistent.

I was one of three parents in attendance; the other two were representatives from the PTA.

“Hey,” one of them said to the other. “I have an idea for next year’s fund-raiser. There’s this group called Equal Exchange…”

I immediately turned around, gave her my name, and told her to sign me up to help. I hope our school pulls it off.

Berman said that in some communities, PTAs seeking to make a change have faced heavy opposition from the established fund-raising companies who don’t want to give up any of their turf. By next year, the Equal Exchange curriculum will be in place, and there will also be possibilities for kick-off assemblies. Instead of an assembly that offers 6-year olds a crash course on salesmanship, Equal Exchange plans to introduce them to the farmers who grew their food, teach a little bit of geography, and let them taste their wares. I imagine my son, who will be in kindergarten next fall, coming home and asking, “Do you know where chocolate comes from?”

I’d buy that line in a second.