Poetic Pauses During the Pandemic

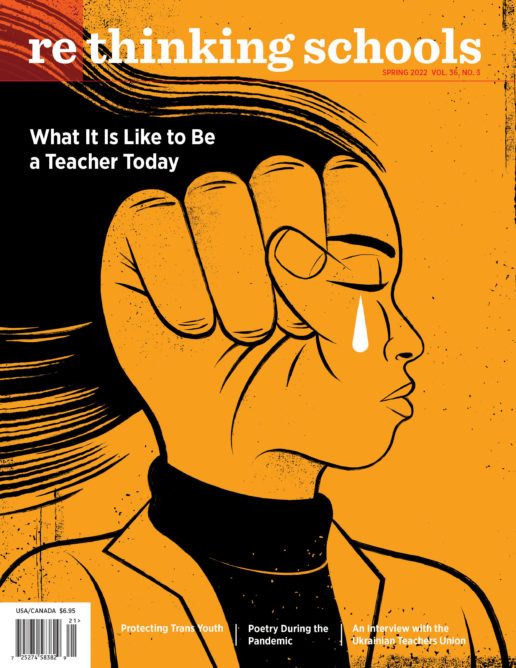

Illustrator: Shadra Strickland

Wrapped in masks and fear, sometimes frozen by the weight of an uncertain future, quarantined back online, suspicious of the inadequate safety measures at their schools, our students are hurting. When apathy, despair, and pain are written across their faces, I need to stop the curriculum train from hurtling forward and provide an opportunity for students to find the ground beneath their feet again, to breathe, to reconnect with their personal histories, to remember moments of strength and solidarity, and to share stories with their classmates. To imagine.

I use “Written by Himself” by Gregory Pardlo for one of these curricular detours, with my graduate students who are all teachers as well as with high school students. Pardlo is a professor and poet whose book Digest won the Pulitzer Prize. Pardlo’s poem tells a mythological story of his birth, giving the reader both imaginative details and historical allusions. I will be the first to admit that the poem is a tough model. There’s nothing straightforward about it except the repeating line, but the repeating line carries the work into the class. The opening reads:

I was born in minutes in a roadside kitchen a skillet

whispering my name. I was born to rainwater and lye;

I was born across the river where I was borrowed with clothespins, a harrow tooth,

broadsides sewn in my shoes . . .I was born waist-deep stubborn in the water crying

ain’t I a woman and a brother I was born . . .

Each of us is born into a place and time and culture and language and people and historical period that remain with us, embedded in the core of who we are and how we live in the world. Sometimes this includes memories like Pardlo’s line about “coffee grounds and eggshells,” which was the way the older folks in my family made coffee too. Sometimes, this includes a historical reference like Pardlo’s line that reminds the reader of baptism and Sojourner Truth: “I was born waist-deep stubborn in the water crying/ain’t I a woman and a brother I was born.” Pardlo brings us into his life in the ways that August Wilson discussed in his essay “The Ground on Which I Stand”:

Growing up in my mother’s house at 1727 Bedford Ave. in Pittsburgh, Pa., I learned the language, the eating habits, the religious beliefs, the gestures, the notions of common sense, attitudes towards sex, concepts of beauty and justice, and the response to pleasure and pain, that my mother had learned from her mother, and which could trace back to the first African who set foot on the continent. It is this culture that stands solidly on these shores today as a testament to the resiliency of the African American spirit.

Calling home into our classrooms — the language, the “notions of common sense,” and “concepts of beauty and justice” as both Pardlo and August Wilson do in their writing — allows us to crowd the room with grandmothers, rivers, sayings, languages of those who’ve gone before. These curricular pauses remind all of us to slow our heartbeats, move away from our fear of the future, by looking to our past, in this case with both facts and fantasy.

Each of us is born into a place and time and culture and language and people and historical period that remain with us, embedded in the core of who we are and how we live in the world.

Examining the Model

Given the difficulty of the text, the number of allusions that students may or may not understand, I launch the poem with that caveat: “We don’t have to understand everything in a poem in order to enjoy it. Poetry can be concrete — something we can feel, smell, see, or touch — and easily understood, but it can also stir our imagination, allow us to dream. We’re going to read a poem where the poet discusses his birth. What I want you to pay attention to is the way he puts the poem together, how he captures our attention. Think about what you can lift from his poem to bring into yours.”

After introducing Gregory Pardlo to the class, I share a YouTube video of Pardlo reading his poem out loud at the New York State Writers Institute in Albany, New York, in 2017. For the first time through the piece, I ask students simply to listen to the poem and notice lines they like or that intrigue them.

Then I give them the text and ask again, “What do you notice?” Students notice the repeating line “I was born,” but also wonder about why he writes about a skillet whispering his name or what it might mean that he was “born a fraction and a cipher and a ledger entry.” They wonder if this refers to slavery because of the ledgers kept of the names of the enslaved. And if they don’t point out the line about Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a woman” speech, I tell them. There are no footnotes to this poem, and frankly, I’m not trying to get them to perform a detailed literary analysis. I want them to come away with the understanding that Pardlo is playing with the notion that our births carry the histories of those who came before: “I was born passing/off the problem of the 20th century.”

Before we move into their writing, I share a poem I wrote as a model for the class to demonstrate how I used his repeating line, but also how I shared my own personal history. This is a teaching move I often employ because I need to figure out whether or not I can write the poem and because another model helps launch student writers. “I used many more specific details from my birth than Pardlo did. It is true that I was born in February, but I made up the storm and my father’s prayers to make my birth seem more dramatic.”

My mother told me I was born in a storm in February

so fierce

the wind flattened trees

against the wall of the mountain,

sheered one side of the forest bald as the storm made its way east,

tossing boats on waves

until my father hunkered on his knees

praying to be saved

inside the belly of his fishing boat.

Because I use this poem as a curricular detour away from despair, I also wanted to seed the idea that neither our history nor our present circumstances need to dictate our future, I added a stanza about being reborn with more strength than I started with.

And then I was reborn

after a man flattened me against the asphalt.

When I rose up, I was a new woman.

I gave birth to myself that night

when my blood tattooed the street

in front of the Catholic church.If there is a baptism in this world

for women,

it comes with blood and tears.

Our rebirth

is our sisterhood.

To move into their own writing, I say: “Pardlo is playful and poetic and not sticking to the factual ‘truth’ of his birth. I didn’t. And you don’t have to either. I want you to use elements of your history, but stretch it, imagine the larger, longer piece of who you are and where you came from.” The idea is to fill their writing well with details and lists, so that when they move to write their poem, they have many details to choose from. This verbal sharing sparks memories as we make our way through the lesson.

I also note that although the assignment is to write about their birth, they might want to use a different repeating line or go off script completely. The idea is to use the poem as a jumping-off point to get students out of their logical brain and into their imagination. Students do not need to copy Pardlo’s style, or even use his repeating line, but they will still benefit from seeing how he put the poem together like Jenga blocks, building with images and repeating lines.

The idea is to use the poem as a jumping-off point to get students out of their logical brain and into their imagination.

I ask, “Where were you born? Sure, you can name a hospital or if you were my grandson, Xavier, the basement of our house with a home birth. Pardlo says a kitchen with a skillet. I might say, a yard with a barking dog and three chickens. On a street that was shadowed by ocean fog and wind.” I pause after each question, allowing students time to make lists. After each list, I ask a few students to share their ideas.

To keep their imaginations brewing, I say, “What foods were found in the house growing up? I might write, ‘I was born to hard tack, lefse, and fish’ because those are the foods that connect me to my father’s Norwegian heritage. What foods link you to your family? To your home?”

Next I say, “Think of school or books. Pardlo writes, ‘I was born a fraction and a cipher and a ledger entry;/ I was an index of first lines when I was born.’ He’s playing with math in the first line and books in the second, but we think it might also be alluding to history. I might write, ‘I was born a poem, hidden in the base of the foghorn’s moan; I was the sadness written into my father’s harmonica.’ I was born in Bandon, Oregon, and the lighthouse let out a low moan on foggy days and nights, and I remember my father playing the harmonica when he was sad. I know all of this, but I don’t know that it was present at my birth, but it is part of my history and my family’s history that I want to include.”

We share our lists out loud as we brainstorm. I encourage them to make their piece “sound like home,” using the names and languages of their home, their family, their neighborhood. Out of the chaos, the sounds, smells, and languages of my students’ homes emerge in poetry.

Once they have their lists of specific words, phrases, and names, I ask them to highlight the pieces from their lists that they want to include in their poem: “The poet’s job is to cherry pick the best details, not use everything from your brainstorming. Find a link or phrase like ‘I was born’ to weave the poem together, and to end the poem with a line or two that ties your present to your past, to your family history.”

This was a quick two-day lesson. One meant to take a break from the heaviness of the world pounding on our hearts. The first day was the examination of the poem, the listing, and the writing. The second day was the reading of the poetry, the learning about each other through these quick study poems. Chloe Maddox, a junior at Jefferson High School in Portland, Oregon, wrote a poem that echoes both the lyricism and the imaginative details of Pardlo’s:

I was born to the cradle of the mountains,

a city of sand and dust

under a sky that swallows everyone whole . . .

I was born to two winds blowing in different directions,

a baptism of the modern kind

I am not a child of my grandmother’s god

even though she prays for me

smiley face on my knee and another on my skull, the uncertainty, the

unsensibility

Los Angeles teacher Norma Mota-Altman, a student in the Oregon Writing Project class “Writing During the Rebellion and Pandemic,” was less whimsical than Chloe, saturating her poem with the stories of growing up in a world where language was both her home and a weapon used against those she loved:

Why was my father so quiet in English when his family stories had everyone laughing in Spanish?

Why didn’t my mother give us tacos for lunch instead of dry sandwiches?

Why was I made to feel that I had nothing to share because I didn’t speak English?

Why were we so different?

Norma took the idea of rebirth in her poem, where she embraced her language that was once taken away from her:

I was reborn into an English-speaking world

Rechristened with the sharp angry sound of NoRma

Rather than the soft caress of Norma

Reborn to competition and “you must do better,”

to foods that lacked chile y sabor

Reborn into a world devoid of comforting arms

Until the Spanish of home once more embraced me

There are days since the pandemic arrived when the world is still too much with me, when my hope and happiness are eclipsed by the overwhelming weight of panic about the direction of the world. On those days I walk in my neighborhood or in Forest Park where the rhythm of my footsteps and the smell of rain or fir trees calms me. Or I find joy and solidarity in my Saturday Oregon Writing Project classes where teachers’ spirits of collective wonderings about how to make their classrooms and schools better give me hope.

Our students need these breaks and camaraderie. Watching my grandson slump against the Pendleton quilt where he’s schooling from our house again after his school returned online after a large COVID outbreak, I know that our students need time out from the weariness of the world. As teachers, we must resist the messages about learning loss and the pressure to relentlessly move forward, attempting to make up for lost instructional time. Instead, I hope we find ways to allow students to remember how to smile across the room, laugh big belly laughs with friends, and shake off the sense of doom by revisiting their past and imagining ways to be reborn into a better tomorrow.