Paradise Lost

Introducing students to climate change through story

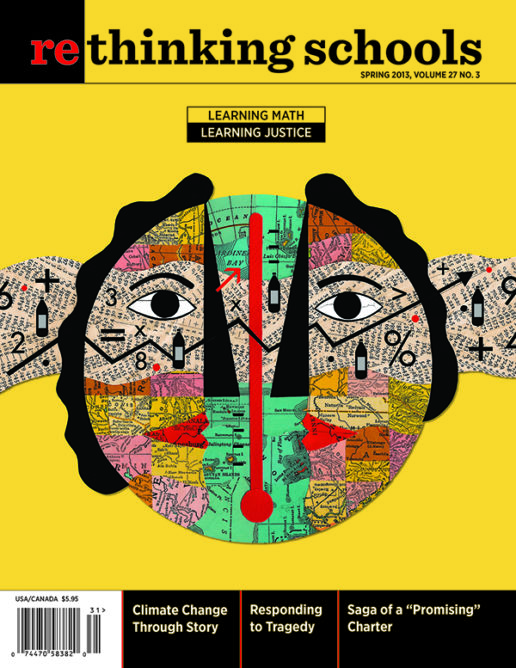

Illustrator: 350.org

“This country has been the basis of my being. And when it’s no longer there, you know, it’s unthinkable.” Ueantabo Mackenzie’s haunting words in the PBS NOW documentary Paradise Lost shook me. I knew I wanted to teach a unit on global warming, especially after participating in the Portland-area Rethinking Schools curriculum group, Earth in Crisis. I didn’t have to be convinced that students need to learn about global warming. It’s one of the defining issues of our time. But Mackenzie’s message startled me: Global warming is here, right now, and it is uprooting people and destroying nations today, starting with Mackenzie’s home on the island nation of Kiribati (pronounced KIRR-i-bas).

I grew up thousands of miles from Kiribati in Arizona. My memories of the changing seasons usually boiled down to something like a shorts season and a jeans-with-sweatshirt season. So in the mid-1990s, when I started learning about the potential climate changes global warming might bring, I was vaguely nervous about the concept, but the danger seemed remote and distant. What difference can a degree or two really make, I thought. At the time I didn’t grasp the rippling effects of global warming, including sea level rise, melting glaciers, and crop failures.

As I was planning my global warming unit—which I first taught to a freshman global studies class and later to a senior humanities class—it was important to ensure that my students didn’t miss the point as I had. I didn’t want them jumping straight into an investigation of the connections between carbon dioxide and rising temperatures, I didn’t want them getting mired in the muck of political debates and international summits—without first hearing about stories like Mackenzie’s. I wanted them to see that, beyond the environmental damage, global warming is about people. Ultimately, I wanted them to care.

I decided that, before we watched Paradise Lost, I would help my students build empathy for climate change refugees and for people whose places are being altered by the changing climate. We started by reading the first chapter of Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, “The First Morning.” I asked students to highlight or underline words or phrases that were powerful, that spoke to them, or that were particularly descriptive. The piece begins:

This is the most beautiful place on earth. There are many such places. Every man, every woman, carries in heart and mind the image of the ideal place, the right place, the one true home, known or unknown, actual or visionary.

Abbey continues with a beautiful description of his first moments in his new home in a trailer near Moab, Utah, and the way in which the sights, sounds, and smells of the area fill him with a powerful sense of connection to that land as home.

After reading the chapter together, my students created a collective “found poem” by calling out the words or lines they highlighted when the moment “felt right.” The result was a poetic group effort that helped them explore Abbey’s use of language to explain the power of place: “Landscape, the appeal of home, humps of pale rock, like petrified elephants, red dust and burnt cliffs, a cabin on the shore, known or unknown, such places, calling to me, apparent to me, beautiful.”

Words and phrases hung in the air until it felt right to end. Then I explained to students that some of the places Abbey wrote about were under attack by developers and dam builders.

After our oral poem, I asked my students why they think places have such a profound effect on people.

Alex said: “Places are important because they can make us feel like we belong. We all need a home.”

“I think a lot of my memories of people are mixed in with the places they took place. Like, when I think of my mom, I remember the house we lived in together and the food she made there,” added Tori.

I loved that some of my students were beginning to personalize the idea of place. To help them go deeper, I borrowed an idea from our Earth in Crisis curriculum group and asked them to do some place writing of their own.

We started by brainstorming places they care deeply about—a special place in their home, at school, or even somewhere outdoors, where they felt like they could be who they wanted to be and felt at peace. It could be someplace from their past or from their lives today. To prime the pump, I listed a few of my own examples: a trail through the forest, a particular soccer field where I enjoy playing pick-up soccer, the garden in my backyard. After picking one of the places on their list, students closed their eyes and imagined themselves in that place so they could absorb all the details like Edward Abbey did. I guided their visualization with prompts:

- Let your mind be a video camera. What do you see? What colors are there and how do those colors make you feel? Are there birds or animals? Maybe people you are close to?

- What do you smell as you look around you? Is it fragrant and floral like the flowers in the background? Does it smell like fresh rain or fried chicken?

- What about the sounds that fill this place? A chirp? The wind blowing through the trees? The ocean lapping at the shore? Your friend or family member’s soothing voice?

- Are there people who help make this place important? What do they look like or sound like? What feelings do they evoke in you?

Students opened their eyes and wrote for the next 15 minutes. Afterward, they shared their pieces with a partner. Then, I asked students to go back to their piece and write about what it would feel like to lose that place, to have that place taken or destroyed. I could tell this last task troubled many students from the sounds of their groans, but they dove into their writing with intensity.

Then, we read our stories together as a read-around. Students’ writing showed a deep connection to place, and they surfaced some powerful memories. Keesha, who was born in Liberia, wrote about a special tree from her village: “Every time I sit under this tree, it feels like nothing exists but nature, no cars, bikes, or smoke. This tree is not just the tree of peace, but the tree of home for many different animals, birds, and bugs. When it rains, I don’t feel it much, so it’s also the tree of protection. At age 9, I lost that tree. I came to the United States, hoping to find another tree like that one, but there’s nothing like it.”

Shana, who lives in foster care, wrote: “Every day I pass by it to and from school and I get a glimpse of my old place I used to call home. I see my mom and me laughing again. I can smell the incense. I can see us singing together as we cook dinner. At times, I just want to run and open the door to my home like I did as a kid. I am no longer that kid and that is no longer my home.”

Erica’s piece was eerily reminiscent of Mackenzie’s words about Kiribati: “I look at that trailer and see my childhood, my laughter, my fear, my balance, my thrills, my questions, my imagination, my safety, my saving grace, my youth. I see the place we ran to when the world wasn’t what we wanted it to be, the place where everything was OK. Some of my heart sings to that trailer. To take it away would be to take part of me away from my soul.”

When the places we love are destroyed or taken away, we lose more than land. We lose part of our identity.

Paradise Lost

Without delving into details about global warming, I had my students jump right into the 25-minute video Paradise Lost. I told them it was an introduction to global warming, and would serve to help them understand why we’re learning about the topic in social studies class in the first place. But it would not go deeply into the politics or science of the issue. I passed out a four-column chart and directed them to take notes about each of the four categories: people/things/objects, actions that happened, sensory details shown or described, and important words spoken. I mentioned that they would be using their notes to do some writing after the video. The 2008 video begins with a United Nations assessment that within the next 50 years, 6 million people a year will be displaced because of sea level rise and storms.

The film follows reporter Mona Iskander as she tours the island nation of Kiribati, which is less than 2 meters above sea level. Thirty-three separate islands make up this country east of Australia, which is disappearing because of rising sea levels. Iskander walks along sandy beaches surrounded by opalescent blue waters. Children play along the surf as fishermen throw their nets into the water nearby. The scene is idyllic and relaxed. Several students said that’s a place they’d want to live. Noa, a recent immigrant from Tonga, said, “That looks like where I’m from.”

The gentle voice of Anote Tong, president of Kiribati, breaks the spell of the enchanting island: “It’s too late for countries like us. If we could achieve zero emission as a planet, still we would go down.” The rising sea level from climate change is swallowing up the island right now.

In her first interview with Tong, Iskander exposes the injustice of the circumstances surrounding the island’s demise: “What does it say to you that the poorest and the smallest countries, which are contributing the least to global warming, are the first ones to be affected by it?”

Tong’s response is compelling: “Unless it hits you in the stomach, it means nothing to you.” Later, he adds, “While the international community continues to point fingers at each other regarding the responsibility for and leadership on the issue, our people continue to experience the impact of climate change.”

Tong’s words cut straight through to the essence of why I decided to lead off my unit with this film. I wanted to inspire my students to care about climate change and also to begin grappling with critical moral questions. For example, is it fair that per capita, the United States emits more than 17 tons of carbon dioxide annually, compared to .3 for the average Kiribati resident, but their land is among the first to disappear? Later in the unit, this foundation would enable us to investigate reasons why U.S. society is structured in ways that encourage and even require such fossil fuel use, to the benefit of multinational energy corporations.

Throughout the film, Iskander documents the parts of the country already destroyed. By the time the film was made, Kiribati had to move “21 homes, a church, even their soccer field, or they would have been swallowed by the sea. The latest scientific reports say that within the century, the sea level will rise between 1 and 2 feet. That means much of this land will be gone.”

The first-person accounts by Kiribati residents are disturbing. MacKenzie explains that the coconut trees, which are a crucial part of their diet and culture, are dying because of the saltwater intrusion. Linda Uan, a local tour guide, shows how the village water sources are now salty and unusable.

These interviews frequently lead to deeply moving statements about how profoundly sad it is to witness one’s place get destroyed. My students were particularly moved by a brief interview with a Kiribati elder named Batee Baikitea who says: “I love my land. If it is going to disappear, I will go with my land.”

Uan adds: “It’s our culture, our lands, it’s everything. Everything’s going to be lost. How would you take that? Losing one’s land is emotional. There’s no joking way about it; it is emotional.”

The movie ends with Tong’s decision to ask the wealthy nearby nations of New Zealand and Australia to take in thousands of Kiribati residents fleeing their island homes. The film raises questions about the obligations that wealthy countries emitting massive amounts of carbon dioxide have to climate refugees, as well as how climate refugees can prepare for the shock of such a move. It’s a challenge the world will increasingly need to grapple with; 6 million refugees a year is no small matter. When I turned on the lights, I let the power of the film sink in for a few seconds as my students looked around at each other in astonished silence.

Kiribati Poems

While the impact of the film was still fresh, I wanted students to put words to Kiribati’s situation, so I asked them to write poems. I discussed several types of poems they could choose to write. They could write a found poem, like the one we collectively constructed as a class after reading Abbey’s piece. Another option was a persona poem written from the perspective of someone or something in the film. “What are some examples of people or things whose perspectives you could write from?” I asked. Students listed options as I wrote them on the board. I was pleased when, after listing some of the Kiribati residents interviewed in the film, students made more creative suggestions: a palm tree, the ocean, the freshwater well, the manieba (Kiribati village meeting center). As new ideas were added to the list, I could see some of my reluctant writers get more interested and less nervous about the assignment.

Wanting to help students think about potential structures for their poems, I provided two models: Linda Christensen’s persona poem, “Molly Craig” (from Teaching for Joy and Justice), and a student example of a found poem. I asked students to notice repeating lines, punctuation and line breaks, and sensory details. We talked about how each of those elements help make the models interesting and add a sense of rhythm. I told students that they didn’t have to choose either of those poetry forms, as long as they conveyed the sense of place, the loss, and the injustice of climate change in Kiribati.

Finally, I provided students with a transcript of the film, so they could re-visit parts of the video that spoke to them.

While students wrote, I projected my computer screen onto the board and wrote my own poem from the perspective of President Tong. Students who initially struggled seemed to settle into their own writing when they were able to watch me work on my own writing. I use this strategy for several reasons. My mid-thought pauses and occasional struggles demonstrate an element of solidarity with the students. Writing is not easy for anyone, me included, but it’s worthwhile to work through the puzzling moments. It also sends a message to students that we are a community of writers, supportive of and respectful of each other’s words. Finally, it helps to establish a culture in which we share our work with each other so that we can grow from each other’s ideas and feedback.

When students finished writing their poems, we took turns reading them out loud. Veronica’s poem, “Dancing as I Go,” was written from the perspective of one of the traditional Kiribati dancers shown in the video:

Dancing as I go

With my feet buried in the sand,

I breathe in the rhythm of the wind and the waves

And wonder: how long?

As I perform the dance of my people to those who visit

I ask myself: will this be my last?

The last of my culture,

The last to pass on the traditions and ways of life,

The last to drink what is left of the remaining

Kiribati water,

And the last to benefit from the bearings of the coconut tree.

Will those who I dance for return for me?

Save me?

Must I disappear with the land I love,

The land that is my home

Dancing as I go?

Lily’s poem was both a celebration of Kiribati culture and a call to action:Before we see the last of the tides come in,

Tell them we are here.

Before these waves beat down the last coconut tree,

Tell them we know. We knew all along.

Before our everything is flooding away,

Tell them about our home.

Tell them of its lush green palm leaves trailing

Across white beaches,

Right up to the blinking blue sea.

Tell them our ways are simple.

We let the sun’s rays walk down our backs,

And we are peaceful,

We are beautiful.

Before the read-around, I had asked the students to “write down lines that evoke emotions or cause you to want to take action, and write down themes that come up in the poems.” After the readings, I asked the students: “So what? Your poems sound like you care about Kiribati. Why?”

Tyler said, “If my house was flooded because of something someone else did, I’d be mad.”

Erica asked, “Is anyone trying to save Kiribati, or are they just going to drown?”

This was the place I wanted my students to get to before we dove deeper into global warming. During the rest of the unit, I hoped their concern for Kiribati would stay with them as they learned that pseudo-scientists were paid to present false information about climate change. They would learn that corporations have tried to point the finger at individual consumers when, in fact, corporate practices are the lion’s share of the problem. They would learn that oil companies spend far less than 1 percent of their budgets on renewable energy development, while making billions in profit and painting themselves green. They would learn that a modern form of colonialism, climate colonialism, continues to exploit our atmosphere and impoverish and destroy countries like Kiribati. They would learn that, despite the warnings and urgent calls for help, nations have not passed binding treaties. In the end, through role plays, simulations, and community action with organizations such as Bill McKibben’s 350.org, I hoped students would see themselves as truth-tellers and change-makers. But it all starts with caring.

The places where we live have a profound effect on our lives. They influence our ideas, beliefs, and how we see the world. Places give us meaning. Our memories make us who we are and are inseparable from the places where they are made. So what happens when our place gets destroyed? What happens to the people who are uprooted, ripped from their homes, torn from their place? We need to stop thinking of global warming as an abstraction. It is Kiribati. It is Katrina. It is Superstorm Sandy. Here in Oregon, it is a future of coastal towns inundated at high tide; increased wildfires, insect outbreaks, and tree diseases; and increased risk of heat stress on crops. Global warming is you and me and all of us. Kiribati is just the beginning.

Resources

- Edward Abbey. Desert Solitaire. Touchstone: NYC, 1968.

- PBS NOW. Paradise Lost. NOW on PBS Video, 2008.