On “Creative Extremism”

In order to fulfill our nation's promise of an equal and high quality education for all children, teachers need to be innovative yet bold as they counter the prevailing political climate.

In “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. addressed his fellow religious leaders concerning the charge of “extremism” they had leveled at him. He wrote:

So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love?

Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice?

Dr. King’s call for the need to be “creative extremists” is especially timely in the current climate of education reform, a climate allegedly concerned with education yet in many ways hostile to it. An important lesson I’ve learned from my many years in education is that teaching is much more than an individual endeavor that brings personal fulfillment; it is above all a social, political, and ethical commitment to young people and to our society’s unrealized ideals of fair play and justice. It is in this context that Dr. King’s words make more sense than ever, reminding us that being creative extremists for equity in education is a worthy pursuit.

Although in our nation all children are promised an equal and high quality education regardless of station or rank, our educational history is brimming with examples of grossly uneven access and outcomes, often based precisely on students’ race and social class. Academic success has been elusive for large numbers of young people who are economically poor or culturally and racially different from the majority. Thus, although an equal education is the birthright of all children, it is a myth for far too many of them.

When young people are denied an equal education simply because of the zip code in which they happen to reside; or when they attend schools with crumbling infrastructures and uncaring educators; or when they face racism and other biases; or when their abilities are doubted: in these cases, we need to be creative extremists to work on their behalf. We also need to be creative extremists on behalf of caring and committed teachers whose work is becoming intolerable because of the growing obsession with test scores and accountability and the diminishing attention to real standards and actual teaching. And we need to be creative extremists on behalf of families, especially those that have little power, in their quest for the education their children deserve.

Like most people, I don’t like conflict, and I certainly don’t seek it out. In my dealings with people, I try to be reasonable, thoughtful, decent, and helpful. I have a hunch that most teachers are like me, wanting to play by the rules and get along. But sometimes these things are simply not enough. It is then that we need to remember Dr. Martin Luther King’s advice to become creative extremists. We can all find ample opportunities to do so in our daily work, whether it’s opening our classrooms to parents and families; or selecting a textbook that is more truthful and challenges the official curriculum; or encouraging students to become critical learners; or joining with other activist teachers to demand better conditions for teaching and learning; or writing books and articles that question taken-for-granted assumptions about the young people in our society. Sometimes just believing in the children who’ve been abandoned by our public schools is the greatest act of creative extremism.

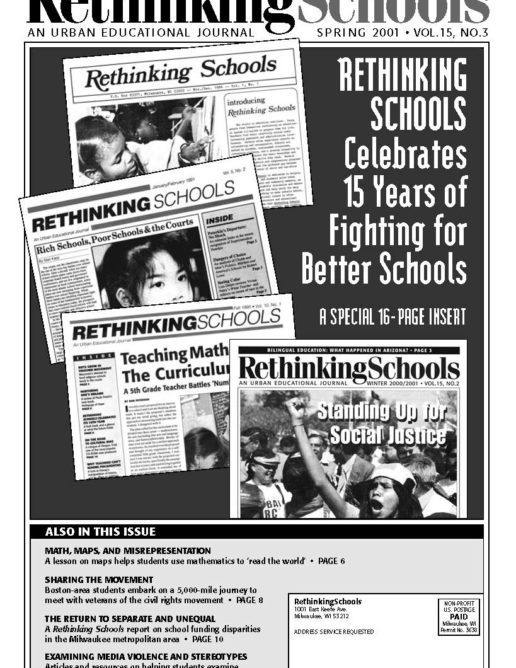

It is fitting to remember Martin Luther King’s words as we commemorate the 15th anniversary of Rethinking Schools, an organization that has taken the lead in encouraging this kind of thinking among educators, families, and citizens. I deeply appreciate the courage, stamina, and integrity that Rethinking Schools brings to our field, and I wish them many, many more years.