“No More Elegies Today”

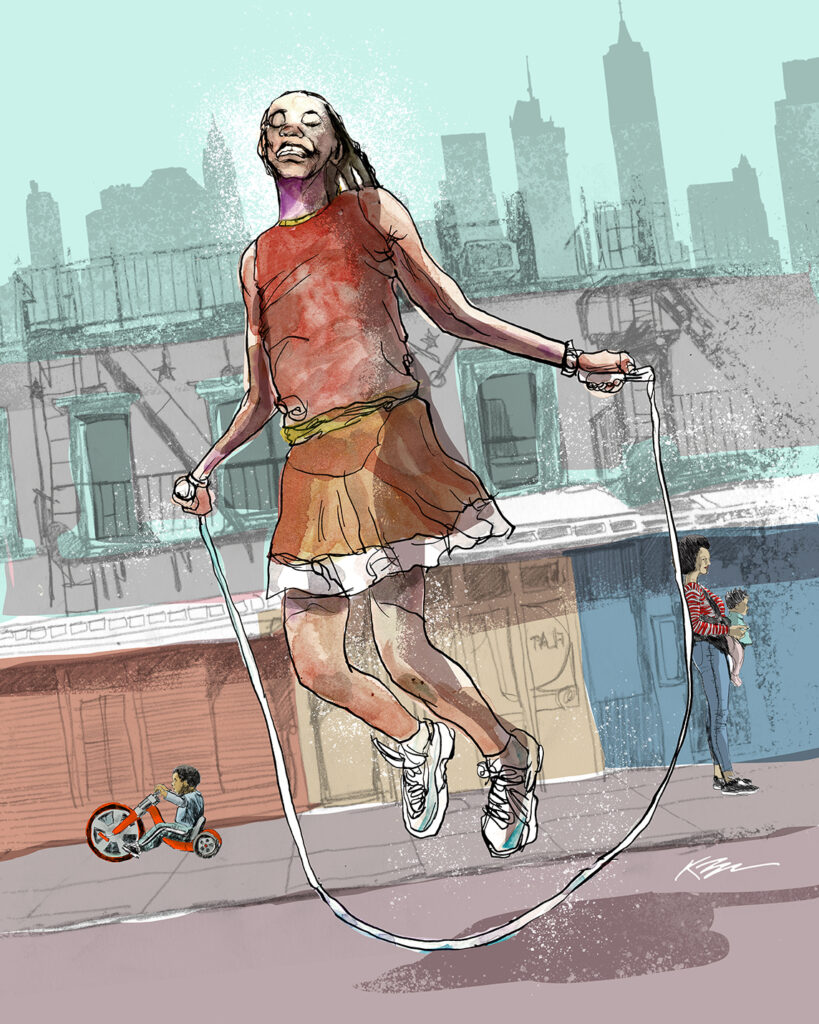

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

When asked about his poem “No More Elegies Today,” Clint Smith said, “Sometimes a poem should just be about a girl jumping rope.

It doesn’t have to be something that is imbued with more despair.” And the same can be said about the classroom. Yes, we must acknowledge and teach about what’s happening in the world, but we also need to help students find and celebrate what they love about their lives. We live in a world filled with war, white supremacy, the climate crisis, a growing unhoused population, gun violence, attacks on women’s and LGBTQ+ rights, and more. Our path to survival must also include memories of all that is good and right: shared belly laughs with siblings and friends, the glory of waves at the ocean, the thrill of catching our first fish, the big hug of a friend who brought us a broom to sweep out the old year.

Poetry provides a way to bring the world into the classroom — all the chaos, the politics, the beauty, and, yes, even the mess. And through the poem, the conversations about the poem and its connection to our lives, we build classroom communities where students can be seen and heard, where they can share their joys, but also their pain and sorrow, and find comfort and new ways of seeing each other. In the wake of the pandemic’s isolation, many have come to understand the necessity of connecting with family and friends.

I taught Clint Smith’s “No More Elegies Today” from his book Counting Descent to remind students of both points: despair and joy. Smith’s poem begins by telling the reader that he will not write a poem about pain, “but rather” about a moment of joy:

Today I will

write a poem

about a little girl jumping rope.

It will not be a metaphor for dodging bullets.

It will not be an allegory

for skipping past despair.

But rather about the

back & forth bob of her head

as she waits for the right moment to insert herself

into the blinking flashes of bound hemp.

By stating that the poem will not be “a metaphor for dodging bullets” or “an allegory/ for skipping past despair,” he acknowledges the presence of those elements in our lives. Then he moves on to elevate a moment of undisputed pleasure: watching a girl jump rope on a playground. There are no bullets rushing past her, no bully stepping into her space, just the bounce of her beads, the “flashing windmills” of her friends’ wrists as they cultivate “an energy of their own.” His poem teaches us to notice, to pay attention to the small delights in our lives — even as we acknowledge the wounds and wounded in the world.

This 90-minute lesson has been successful in multiple spaces: with graduate-level K–12 teachers in my Oregon Writing Project class at Lewis & Clark College; with 10th–12th-grade students in Blair Hennessy’s Future Educators Pathway class at Lincoln High School with majority-white economically privileged students, and in Dianne Leahy’s 9th-grade language arts class at Jefferson High School with majority students of color from mixed-income homes. The one differentiation I made was in Blair’s class. Because these students are studying education and some are in elementary and middle school classrooms, I encouraged them to think about what students take away from the lesson about writing, the world, and their own lives.

Listen and Notice

In each class, I begin by introducing students to Clint Smith. I share his website photo and give a brief background: He was a high school English teacher; he is a staff writer for The Atlantic magazine; he is the author of the amazing nonfiction book How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, which has won numerous awards, and finally, he is the author of a poetry collection Counting Descent, which includes the poem we are about to read. Before we launch into the lesson, I ask, “Does anyone know what an elegy is?” If no one knows, which happened in two of the three classes, I tell them that an elegy is a poem or song expressing sadness or grief about someone who died.

Then I distribute Smith’s poem and instruct students to listen as he reads the poem during an interview with PBS. I say, “The first time through close your eyes and let the poem wash over you.” The second time through, I ask them to listen with a pen in their hand. I ask, “What do you notice about the content of the poem? What strikes you about what he writes about? Anything you notice is fair game. There are no right or wrong answers. Also, as you read back through, notice how he constructs the poem. Is there a structure? Mark up the poem with your noticings.”

In each class, I first give students time to process the poem on their own, then with a partner or small group to deepen their understanding by hearing other people’s reactions. I walk around and listen, taking notes as students speak to remind myself who I might call on when we return to the larger group. Despite the wide range of race and class and age differences in the three communities, students had strikingly similar responses to the poem. Isabel observed, “Smith humanizes the girl, gives her an identity we can all relate to, whether we have jumped rope or watched someone. We are there in the playground with her.” Charlotte noted, “He’s saying kids should be allowed joy.” And Aidan discussed the “nostalgia” in the poem, the way we can feel and hear the poem in our bodies with the “rope skipping across/ the concrete.” Ellie added thoughts about the structure of the poem, the way Smith layered in contrast with this statement, “It will not be a metaphor for dodging bullets./ . . . But rather about . . .”

Once we process the poem together for content and style, I share a quote from Smith’s 2016 PBS interview with Mary Jo Brooks, who wrote:

After a year of writing poems that focused on violence, Smith realized that he also needed to write about the small activities of joy that happen every day, whether it’s his parents dancing in the living room or children playing in the school yard. . . . [Clint Smith] penned the poem “No More Elegies Today” as a way to help illustrate that complexity. He said poetry for him is always about trying to make sense of the complicated world that he inhabits.

After a volunteer reads the quote out loud, I encourage the class to return to the poem and remind themselves where Smith teaches us how to acknowledge suffering without losing our capacity for pleasure. How does the poem “illustrate” that complexity? Students point out the way he lists first the “despair” that he will not talk about before he moves on to discuss the girl jumping rope.

I pause first at the despair. I ask students to make a list of the happenings in the world that they don’t want to become numb to. “What hardships or violence or sadness or pain need to be humanized and named?” Often, in teaching, I share pieces from my own life to help them with their listing. During this lesson, I recalled my father’s death. “I don’t want to become numb to the harsh realities in our daily lives.” I tell them. “I was 13 when my father died, and I remember that at his funeral people chatted and laughed. I was furious. My father was dead. I wanted everyone to cry. Now that I’m older, I understand how bitter and sweet can reside in the same moment. Yes, they were sad, but the laughter was about sharing memories of my father.” I tell them about when I took my 5-year-old grandson to his daycare and walked by tents inhabited by unhoused people, how we greeted each resident when and if we saw them, how we talked about what it might be like to live without water or a bathroom or lights, about how unfair it is that some people have two houses and some are forced to live on the streets. During my visit to Jefferson, I discussed the protests at Tubman Middle School, where I walked with my 7th-grade grandson and his classmates to the district office to protest the number of substitute teachers and chaos at his school. (Six of his seven classes were taught by substitutes during the spring semester.) Most students in Ms. Leahy’s 9th-grade class had been 8th graders at Tubman during the protests, so they picked up the conversation about how some of their friends at other middle schools had the same teachers all year, while Tubman students had roving subs, often unfamiliar with the subject area.

After about five minutes, I tell students to share with their small group or partner, depending on the room setup. “Listen with your ears and your heart as your partners share their lists. If they say something that you haven’t thought of, you can add it to your list. Sure, this is a sharing time, but it is also a conversation time about the world.” This conversation warms the ground for writing, loosens our shoulders, reminds students of the knowledge and memories they bring to the classroom.

When we come back to the large group, I encourage students to share their ideas, either by discussing what came up in their group or by nominating someone to share. Because I have walked around the room eavesdropping on conversations, I also remind groups of ideas I overheard. The catalogs of despair were similar from each of the three groups, although often discussed in different order: gun violence, especially in school shootings; abortion rights; climate crisis; war; bigotry in schools; pandemic isolation and deaths; mental health; sexual harassment; substance abuse; the unhoused epidemic; the rise of hate crimes against people of color; and suicide.

Then I move on to explore the second part of Smith’s poem: joy. “What joy do you find in the world?” I prompt. “What do you want to remember at the end of the day? At the end of the year? Clint Smith notices a girl jumping rope. What do you notice that brings you moments of delight? Is it that delicious shrimp dish your grandmother makes? Is it the Pop-Tart that warms you in the morning? Is it playing a game with your family or friends? Is it walking in a park and watching the antics of squirrels? The way your cat twitches her tail when you say her name? List every little thing that makes you smile.” I ask for a few volunteers to share to kick off this on-their-own quick writing time.

When the pencils slow down, I say, “When you share with your group, gather their ideas too. Maybe you forgot to mention picnics and river swims with your grandmother or the thrill of dancing with your friends.” Laughter and mostly engagement follow this prompt. When I invite students to share ideas, the lists are long and detailed and diverse: competitive card games, cooking pasta with their mother, bonding with teammates, holding hands with a boyfriend, lazing by the fire, sleeping in, enthusiastic greetings of pets, the last five minutes of practice. For Elijah it was winning at computer games with his friends; for Camila it was making presents for her family; for Tommy it was playing hide-and-seek and skateboarding with friends at Lloyd Center, a mostly empty, once-thriving indoor mall. Although their lists varied, what most students shared was time with family and friends. Their responses made me wonder if the lists would have been the same prior to the pandemic and the isolation that followed. Perhaps we treasure our time together more now that we understand what it was like to lose it.

Examining Poetic Structure

At this point in the lesson, we return to look more closely at how Smith’s poem works. When I instruct students in any genre of writing, I use the mentor text to teach them to observe the underlying structure and the strategies the writer employs. This method of teaching pushes students to learn how to track a writer’s moves, so they can include them in their own work, but also how to use the same methods again and again as they face new writing challenges when there is no longer a teacher at their elbow. Our question as writers is: How did the poet or novelist or essayist do that? Develop character? Write compelling dialogue? Use poetic language in an essay? Or in Smith’s case, move from despair to joy? I ask students, “What ‘hooks’ does Clint Smith use to pull his poem forward? Are there repeating lines? What do you notice that you might use to help you write your poem?”

After they have marked up their poem for a third time, they share with a partner. I remind them to refer to the poem. This is a skill-building exercise. Often the first times I do this, students do not know what to look for. I give them hints: repeating lines, words or phrases that move the poem in a new direction. Because both Blair Hennessy and Dianne Leahy are OWP writing coaches, their students know how to find the “bones” of the poem. They notice the opening: “Today I will/ write a poem/ about . . .” as a possible hook they could use. They also notice the way Smith moves to what the poem will not be about. We briefly note that he uses the terms “metaphor” and “allegory,” and we brainstorm other words they might use. And finally, we examine how he uses the phrase “but rather about” to turn the poem toward joy.

After writing Smith’s phrases on the board, I say, “We are going to write in silence for the next 15 to 20 minutes. Remember, poetry is about noticing how someone else experimented, then working on your own experiment. Maybe try one of Clint Smith’s lines or maybe change the line to suit your writing. Go back to your lists as you start your poems. You might begin as Smith did by writing about what you don’t want to become numb to or what this poem is not going to be about. Then go to your joy list and write about what you want to remember. You can go into details about one memory or add more. There is no way you can be wrong, except not to write.”

Let me pause here to say, sometimes when I conduct writing workshops teachers will raise the problem of getting students to stay with the topic. For me, the point is not to get students to adhere to the exact prompt, it is to get students to write. One student lowered his head to his hands during writing time. When I paused in front of him, I asked him if he wanted to talk about his poem. He picked up his head and said, “I don’t want to write about any of this.” Clearly, he hadn’t listened when I said he didn’t have to; he’d disengaged before I got that far. “You don’t have to. What do you want to write about?” Sleeping in. “Go for it. Tell me about finding the cool side of the pillow. What blankets you love. Just get detailed.” He didn’t write a great poem. Again, not the point. I don’t care if students follow the rules or the prompt exactly. I want them to locate and find topics that wake up their sense of themselves as writers.

Sharing the Writing

Writers need real audiences beyond the teacher. I rarely ask students to write anything that they don’t share. When I was a full-time high school teacher, we conducted regular read-arounds where everyone shared their poetry, essays, and narratives — or at least a part of them. In my graduate classes, we don’t have time for a full read-around, but we always share in small groups followed by a few people reading their pieces to the larger group. This was the routine we followed in both the OWP class and Blair’s Future Educators Pathway class.

To launch the sharing session, I give the following instructions: “As each of your classmates reads, please listen with a pen or pencil in your hand, jot quick notes about what you love or connect with in their writing. After each person reads, stop and take a moment to celebrate their writing by telling them what you love. You don’t need to tell them how to improve. That’s not your job today. Today is all about what is right and good in the writing. Writers, no need to apologize. You only had 20 minutes to write, so just read your writing and revel in the praise.”

At Jefferson, Dianne constructed a stage that she pulls out for read-arounds, and she bought a stand-up microphone. She also has a stash of treats for every reader: candied apple suckers, chips, sparkling water. Almost every student in her class read before the final bell. As I mentioned earlier, most of these students attended the same middle school, and they are enthusiastic cheerleaders for each other, encouraging classmates to get up and read, and clapping and whistling after the poem is finished. Although Dianne has taken the art of the read-around to a new level, I believe that this piece of “publishing” student writing is an important step in teaching writing as well as building community.

Learning from Student Writing

Some students’ poems followed the format, others didn’t. The results were equally insightful. In listening first as they shared their writing in class and then again as I reread their pieces, I learned about their lives — their losses, their fears, but also how they moved into recollections of small moments of delight that they surfaced with exquisite detail:

Today I will write a poem about myself.

It will not be about my tortuous relationship with my father,

or about how every time I see that person in public

my lip trembles,

and my vision goes blurry.

But rather about the time I was kissed in the rain,

or the time I was proposed to with a blue raspberry Ring Pop.

Serena’s piece becomes a cumulative poem, riffing off Smith’s one moment of joy into a series of moments, which many 9th graders emulated:

Maybe I’ll write about when I

watched the northern lights inIceland

on the roof of a car,

my favorite antique store,

or the first time I watched Breaking Bad,

but I will not write about my first real boyfriend;

the coercion,

and the unwanted hands that roamed my 14-year-old body.

Instead,

I will write about when I finally found Midnight Marauders on vinyl,

or about how every night

I dance around to Erykah Badu with my cat wrapped up in my arms.

I learned how young women still find ways to beat themselves for their bodies’ imperfections as Lucy does in her poem:

I won’t think about the way my stomach rolls underneath my shirt

I won’t think about looking into store

windows at my reflection to check how I lookI won’t think about comparing myself to all of my beautiful friends

But I also applaud the way writing the poem pushed Lucy beyond criticism to find scenes of joy:

Instead I will think about how

piercing laughter erupts wheneverI play cards with my friends

Instead I will think about how the

soft carpet touches my skin asI lie on it

Instead I will think about how my

friend looks cute with her templeswrinkled together in focus

Instead I will think about how a new

deck feels slick and cold in myhands, careful not to ruin it

Their pieces also become part of the next generation of prompts and models for students. Even in this iteration of the lesson, I was able to use poems from Blair’s class of juniors and seniors to share with Dianne’s 9th graders; their models were more accessible than mine.

And What Did You Learn About Teaching?

In the last five minutes before the final bell rang in Blair Hennessy’s Future Educators Pathway class, I asked students what they took away from the “No More Elegies Today” lesson about teaching. Their astute observations helped me re-see my own teaching. One student talked about the interactive nature of the lesson, the way my teaching was a conversation between the teacher and the students that allowed a lot of time for students to engage with and learn from each other. Another student, a senior, said how much she enjoyed sharing her joys and hearing her classmates talk about theirs. She noted that schools rarely ask students to share their lives and they need to spend more time in this way. I agree.

This is a lesson that can elicit great poems, and it certainly is a lesson that teaches students how to read poetry; how to look for patterns, language, content and style; and how to use that knowledge as a jumping-off point for their own work. Clint Smith’s poem and this lesson also allow students time to pause and to find new ways to look at the world: to see, acknowledge, and take refuge in the moments of connection and celebration. Smith’s words remind us that life is not just homework assignments, war, and violence, but also about the laughter of friends, the delight of curling up in front of a fire and getting lost in a novel, the thrill of evading security patrol as you play games in the mall, the joy of discovering a varied thrush in your yard. This is building a habit. As much as it is a habit to find and interrogate the inequalities and the injustices that we see in the world, it is also a habit to notice and take delight in what brings us joy.

No More Elegies Today

By Clint Smith

Today I will

write a poem

about a little girl jumping rope.

It will not be a metaphor for dodging bullets.

It will not be an allegory

for skipping past despair.

But rather about the

back & forth bob of her head

as she waits for the right moment to insert herself

into the blinking flashes of bound hemp.

But rather about her friends

on either end of the rope who turn

their wrists into small

flashing windmills cultivating

an energy of their own.

But rather about the way

the beads in her hair bounce

against the back of her neck.

But rather the way her feet

barely touch the ground,

how the rope skipping across

the concrete sounds

like the entire world is giving

her a round of applause.Excerpted from the book Counting Descent by Clint Smith. Copyright © 2016 by Clint Smith.

Reprinted by permission of The Gernert Company.