‘Narrow and Unlovely’

How a market-based educational experiment is failing New Orleans children

Illustrator: Reuters/David J. Phillip/Landov; UPI Photo/A.J. Sisco/Landov

© Reuters/David J. Phillip/Landov

“What the best and wisest parent wants for his own child, that must the community want for all of its children. Any other ideal for our schools is narrow and unlovely; acted upon, it destroys our democracy.”

— John Dewey,

The School and Society, 1907.

“I’m a real-estate developer;

I don’t know the first thing about running a school.”

— James H. Huger,

chairman of New Orleans’ Lafayette Academy Charter School, in a 2007 Atlantic Monthly article.

In late August 2005, Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast and shattered New Orleans’ already troubled public school system. Over half of the city’s school buildings were destroyed, and tens of thousands of students and teachers were scattered across the country.

While the inertia of the federal response to the disaster sparked anger and action across the country, one sector moved through the wreckage with stunning efficiency: conservative education reformers. To them, Katrina was a gift. “In the case of post-hurricane New Orleans, American school planners will be as close as they have ever come to a ‘green field’ opportunity,” said Paul T. Hill of the Center for Reinventing Public Education on Sept. 21, 2005.

Prior to Hurricane Katrina, the New Orleans Public Schools (NOPS) served 63,000 students, mostly low-income and almost entirely African-American. Like many other urban districts, the district was faced with a declining tax base and a dwindling student enrollment. It was widely assailed for corruption and academic failure.

During the year following the storm, conservative activists from outside the city paved the way for a new type of public school system. It positions schools as competitors, and families and students as consumers. And, rather than bringing communities together to work for the reform of all schools for all children, it creates a system where winners and losers are inevitable. In fact, that’s part of the design.

Desperate Communities

Many of those who saw green in New Orleans were members of the Education Industry Association—the trade organization representing corporations that market services to schools and school districts. Others included conservative think tanks like the Center for Education Reform, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, the Heritage Foundation, and the University of Washington’s Center for Reinventing Education. For years, these well-funded and well-connected institutions and interests have argued that public schools and school districts ought to join the free market economy. In the emergence of charter schools in the early 1990s, these reformers saw their opportunity: charter schools present the vehicle for outsourcing. “Choice” and “competition” could become the new clarion call. Conveniently, such a model also created a multi-billion dollar market for the services some of them sell.

The reformers, who have the ear of the Bush administration, have built a public relations machine that blankets the airwaves with the message that public schools are failing, and that bloated bureaucracy, uncaring teachers, and selfish unions are to blame. Dismissing the role of state funding structures that create inherent disparities between property-rich and property-poor school districts, the movement promotes an individualistic, rather than a collective response to the challenges facing public education. Rather than joining together to demand equity and excellence in our public schools, the message implies that conscientious parents can and should jump ship.

In struggling districts with declining participation and support from the middle class, the pitch for independent schools is a powerful tonic. It has created a painful wedge in many of these predominantly African-American communities, dividing families and neighbors who hold strong allegiances to their historic public schools yet are compelled to pursue the enticing promise of change for their children. The elixir of an individual bailout option not only divides communities, but also weakens the political will for collective action in support of public school systems.

The Takedown

Within days of Hurricane Katrina, conservatives were lobbying aggressively in Baton Rouge and Washington. The message was clear and compelling: The storm is an opportunity to experiment at scale with a free-market construct for public education.

Within two weeks of the hurricane, U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings referred to charter schools as “uniquely equipped” to serve students displaced by Katrina. Two weeks later, Spellings announced the first of two $20 million grants to Louisiana, solely for the establishment and opening of charter schools.

In October 2005, Louisiana Gov. Kathleen Babineaux Blanco issued an executive order waiving key portions of the state’s charter school law. The executive order, which remains in effect today, allows public schools to be converted to charters without the input — or even the knowledge — of the school’s parents and teachers. A month later, the state legislature voted to take over 107 New Orleans Public Schools, and place them in the state-controlled “Recovery School District.” Finally, in February 2006, all 7,500 teachers, custodians, cafeteria workers, and other unionized employees of the devastated district were fired.

Within six months, while the city was largely devoid of residents, the infrastructure of the New Orleans Public Schools was largely gutted and a new framework positioned in its place. It was almost entirely what the market reformers dreamed of: “Choice” for individual families and “competition” among schools that would pressure them all to improve.

That, at least, is the promise.

There was little commitment that residents of New Orleans participate in the planning and rebuilding of their school system. The dismantling of the New Orleans Public Schools began in earnest before the floodwaters had fully receded, while most of the city’s residents — particularly those from communities most heavily invested in the public schools — were still dispersed across the country.

The Build-Up

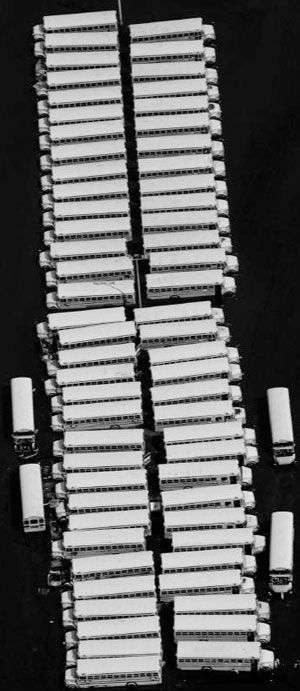

© UPI Photo/A.J. Sisco/Landov

Louisiana’s 1997 Charter School Demonstration Program doesn’t envision charters as a means to privatize or deconstruct public education. The purpose of charters, according to the law is to create “innovative kinds of independent public schools” that experiment for the good of the entire system. Positive results would be “replicated, if appropriate, and the negative results identified and eliminated.” Applicants for a charter must be nonprofit organizations, and they must articulate their pedagogical strategies and operational plans for the new school. The language of the law, in other words, does not envision a free-market agenda.

Suddenly in control of over 100 New Orleans schools and dozens of unusable buildings, uncertain how many residents would return to the city and where they would be, and with federal money flowing for charter schools, the Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education (BESE) had a daunting task. Given their evident disdain for anyone connected to NOPS, they sought guidance away from New Orleans, and even Louisiana.

To manage the screening and evaluation of charter proposals, the BESE turned to the Chicago-based National Association of Charter School Authorizers. Among its members are many for-profit education management organizations, including Edison Schools, Mosaica Education Inc., and SABIS Educational Services. The decision to allow the charter school association to select the charter applications to be approved by Louisiana may have been done for expedience. But by moving the chartering process away from New Orleans, the state put local educators and grassroots community groups interested in reopening their local schools at a grave disadvantage.

The first to respond to the call for proposals in New Orleans were those with pre-existing resources or expertise. The early birds included well-connected parents and friends of the already existing Lusher K-6 charter school in the city’s affluent Garden District. The group had sought permission to expand their school the previous year, but had been turned down. In October 2005, the Lusher board appealed to the Orleans Parish School Board (meeting for the first time since Katrina, in Baton Rouge) for permission to extend their school through 12th grade and to prioritize enrollment for the children of returning faculty members at nearby Tulane University. In the absence of any community hearings or public debate, the school board not only green-lighted Lusher’s expansion plans, but also agreed to hand over the historic Alcee Fortier High School building to accommodate the added grades.

Another early proposal called for the creation of a charter association that would reopen all 13 schools on the city’s West Bank. And so at the same October board meeting in Baton Rouge where the board gave Lusher the go-ahead, the board blessed the creation of the Algiers Charter School Association.

As fall turned to winter, both the Orleans Parish School Board and the BESE authorized more charter schools. The official applicants were local non-profits, many of them created for the sole purpose of applying for a charter, and several of them wasted no time in sub-contracting with national for-profit entities to manage the schools. Contracts were extended to some of the industry’s biggest players including The Leona Group, SABIS, and the nonprofit Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP).

Closed Doors and Safety Nets

By spring 2006, 25 public schools had opened in New Orleans. Eighteen (72 percent) of those were charter schools, and 14 (56 percent) had established “selective” admissions policies. In addition to the charter schools, the Orleans Parish School Board opened five schools in the city. In summer 2006, as families began to flood back into the city, the state conceded that it, too, would need to open and operate some schools. The Recovery School District opened 17 state-run schools that fall.

Parents returning to the city have had to negotiate a complex landscape to get their child into school. Registration is handled at each individual charter school, so parents must crisscross the city (with virtually no transportation infrastructure) to research schools and register their children. There are no neighborhood schools that students are entitled to attend. There has been no oversight to ensure that schools are opening in the places where returning families are living. It is a challenge, even for the savviest parents with ample time on their hands.

Questions of access began almost as soon as the school doors swung open. Or, perhaps more appropriately, as they swung shut. Most charters quickly met their enrollment goals, and then closed their doors.

This contractual right of charter schools to limit access is a key distinction between charter schools and traditional public schools. Without collective responsibility for educating all children in the system, charter schools in New Orleans have been permitted to cap their enrollment to maintain an optimal student-to-teacher ratio of 20:1. Unlike traditional public schools, which must provide access to all children within their defined geographic boundaries, the flood of students returning to New Orleans from spring 2006 through early fall often found themselves shut out of the most promising schools. Particularly hard hit has been the city’s very large population of children with special needs or disabilities. These students have seen closed school doors far too often.

The inevitable flaw in New Orleans’ experiment with free market schools

is in the distinction between “competition” and “collaboration.” Collaboration lifts all boats. Competition determines winners. Some kids — returning late, or without their parents, or with parents who couldn’t navigate the right channels — were sunk.

Choice and the ‘Un-chosen’

While charter advocates insist that their schools are open to all, many charter schools engage in practices that have raised concerns in other states about “creaming.” One example is the “KIPP Commitment to Excellence Form” which prospective parents and students at all KIPP schools must sign. The commitment outlines KIPP’s expectations, including extended days, Saturday school twice a month, and summer sessions. It commits parents to reading to their child nightly, and being available to the school when called upon. The contracts also include a strict student behavior code. Failure to adhere to the commitments by either the parents or students may result in dismissal.

In a 2006 study of charter schools, researchers in Maryland expressed concern that such contracts might deter or preclude many families from enrolling in a KIPP school. They also found that KIPP schools were not hesitant to ask students to leave—not just if they stepped off the path, but also if the parents did not live up to expectations. Public schools rarely have that luxury.

Pushing out students who don’t fit the behavioral or academic norms of the school is also easier for charters. In March 2007, the first anecdotes of this practice began to emerge from New Orleans. At one Recovery District school, the principal complained that a number of students had arrived mid-year with strikingly similar stories. Each had been at a charter school. Each was having learning or behavioral difficulties. In each case, the parent had been called in and told that their child would be expelled from the charter, and consequently would be unable to enroll in any New Orleans school until the fall. However, the parent was told, if you “voluntarily withdraw” your child, a Recovery District school will be obligated to accept them this school year. Not coincidentally, the principal speculated, the students arrived just one week before the state’s standardized assessment was to be given.

As the schools of last resort, the state-run Recovery District schools have been hobbled from day one. When 17 RSD schools opened in mid-September 2006, students were confronted with all-out chaos. Textbooks had not arrived; buildings were not furnished with desks, let alone computers; and meals were frozen. And some schools had the undeniable feel of holding prisons; discipline replaced academics and security guards literally outnumbered teachers. As more and more children returned to the city, these schools struggled to accept them, because the charter schools would not. In January 2007, when newspapers reported that over 300 children had been waitlisted, even for RSD schools, the Recovery District rushed two additional schools into operation. Class size in some buildings ballooned to nearly 40:1. One English teacher reported having 53 students in one class.

Unequal Resources

The charter movement’s competitive mentality, with its deep-pocketed supporters, has created vast disparities in New Orleans. When Lusher Charter School was handed the Alcee Fortier High School for the expansion of their program, the building, like many other New Orleans public school buildings, was in disrepair. But as a charter, Fortier was able to access $14 million in state dollars, as well as over $1 million from Tulane University to complete a top-to-bottom renovation. Across the river, the Algiers Charter School Association initiative is heavily underwritten by Baptist Community Ministries, the state’s largest private foundation. On the strength of private support like this, Algiers reported in July 2006 that it had a $12 million reserve fund.

In contrast, a few months later, RSD’s superintendent was assuring the media that her teachers were learning how to teach “creatively” despite the lack of textbooks.

Despite the obvious inequities, it is too early to know how New Orleans’ many charter schools will perform academically. But the amazing thing about the hype and riches associated with some charter schools is that their academic record nationwide is abysmal. In city after city, charter schools have failed to produce academic gains comparable to their co-existing public schools.

Market Values

In a system based on competition, there’s no premium on sharing successful models. There’s no percentage in transparency. The principle of competition is antithetical to the concept of a public school system. “Choice,” however appealing in concept, is problematic.

Inherent in the concept of “choice” is the need for a parallel set of universal access schools for those who fail to choose, those who are “un-chosen,” and for those who choose to stay with their community-based or fully public school.

There are steps that could be taken now by Louisiana to restore a sense of community to the New Orleans Public Schools. The governor should immediately reinstate the provisions of the state’s charter law that require community and teacher approval before any public school can be converted to a charter. There should be a moratorium placed on the granting of any new charters until the city, through an inclusive and comprehensive public process, develops a vision and mission for its public education system.

Meanwhile, there must be at least a minimal centralized function in New Orleans that guarantees equity in the areas of finances, access, and staffing. If the state believes (most educators would agree) that student to teacher ratios around 20:1 are optimal for student learning, as they apparently do when it comes to charter schools, then the system must aggressively drive to ensure that all students are in such classrooms. If the state believes that students in charter schools deserve the most highly qualified teachers, then the students in the traditional public schools must have those teachers as well.

These promises can be kept only when a community wants the best for all of its children. A market-based system will never provide that.