Michigan Reform: Controversy Escalates

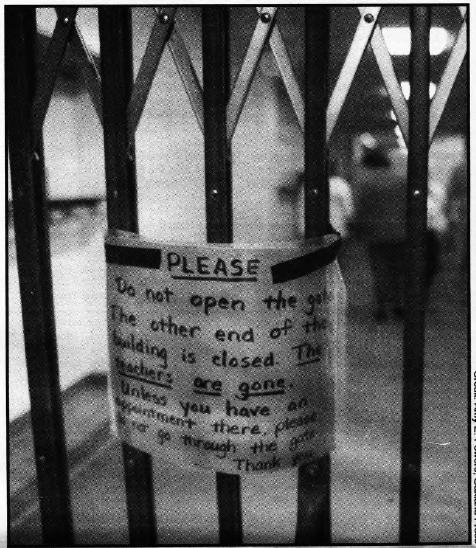

KALKASKA, Mich.— Sandwiched among the pine forests and trout streams of northern Michigan, the well-maintained schools of Kalkaska seems to belie the stereotypes that surround a financially strapped school district. But the district garnered international attention two years ago when its schools closed on March 24. Faced with voter rejection of property tax increases needed to keep the 2,300-student district going, the school board decided it would rather shorten the school year than cut the heart out of the district’s programs.

“We had enough money to go the full year, but only if we wanted to decimate everything from athletics to calculus,” explains Kalkaska Superintendent Doyle Disbrow. “We chose not to do that. We decided that all of our programs were important, in fact more important than going for 180 days.”

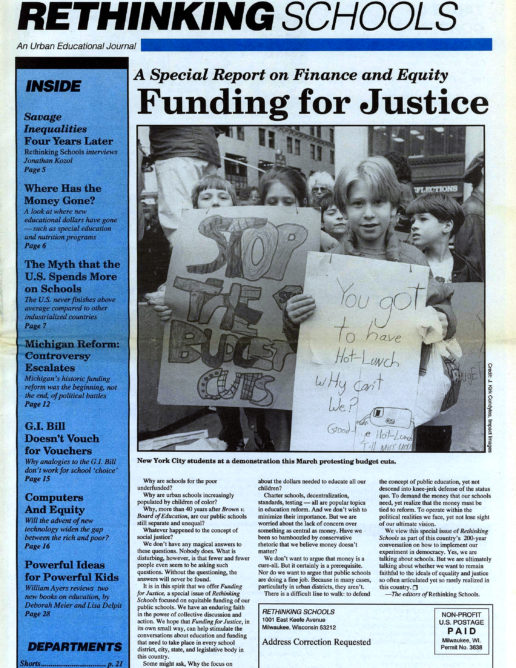

Some 53 television stations and hundreds of radio and print journalists descended on the town on that last day of school in 1993. “It was a circus we didn’t expect,” said school board member Diana Needham.

The Kalkaska situation highlighted the national crisis in school financing and helped propel an overhaul in Michigan that drastically reduced schools’ reliance on local property taxes and increased state funding. Today, the schools are open again in Kalkaska. The novelty has worn off, the journalists have moved on, and the circus is over. But the problem of adequately funding the schools continues, albeit less severely. Disbrow notes that as part of its landmark legislation increasing state funding of schools, Michigan also restricted increases in school budgets. Further, the state monies are based primarily on an increased sales tax, a less stable form of funding than property taxes.

“Within three years, all districts are not financially going to be able to fund the programs that they currently offer,” Disbrow predicted to Rethinking Schools. “That’s the bottom line.”

Others are less pessimistic about Michigan’s finance reform, which was passed by the legislature in 1993 and approved by voters in March 1994. They underscore that the reform reduced the worst of the inequities in funding, made schools less reliant on the whims of local property tax owners, and included additional funds for schools based on the number of students receiving free federal lunch. But even they note that the day of reckoning has been postponed, not eliminated.

“Michigan is riding the wave of an economic boom right now,” notes Professor David Plank of the Department of Educational Administration at Michigan State University in East Lansing. “But two or three years hence, when the economy turns down again, it will be difficult to find the money, and it will set up a big fight between schools, universities and prisons — which are the big items in the budget.” (As with many states, Michigan has greatly expanded its prison system in recent years. From 1984 to 1994, the state’s prison population nearly tripled and Michigan spent $1 billion on new facilities. Nonetheless, there remains an overcrowding crisis and state prisons are expected to run out of space by this summer, according to the Lansing State Journal.)

Furthermore, resolving the funding crisis did not eliminate controversy over education. Today, Michigan is embroiled in a fierce debate over statewide standards, state regulation of schools, and charter schools. The conservative/business Republican coalition that backed the funding reform is showing signs of strain as an increasingly aggressive radical right is questioning what had been a consensus among the corporate community: that increased state funding would be tied to increased state standards and oversight. Republican Gov. John Engler – an astute politician with his sights on the vice presidency in 1996 — has apparently decided to side with the radical right on school issues and shore up his support among Christian conservatives, who are the dominant force in national Republican politics.

“The right has been outflanked by the radical right, to the extent that Engler is back-pedaling away from the business community’s agenda of state standards,” notes David Labaree, a professor of teacher education at Michigan State University. “It seems that the libertarian right, the anti-government right, is winning for now.”

Taxes, standards, charter schools, testing – the Michigan situation highlights the complexities facing states and schools across the country as they address the twin problems of funding and reform. It also underscores the point that while one may want to separate funding from other issues, the real political world rarely operates that way.

Michigan’s Tax Revolt

There is unanimity across the political spectrum that Michigan’s school funding reform was fueled primarily by anti-tax sentiment, not concern with education. Issues such as increased equity, state standards, and charter schools were piggy-backed onto this anti-tax ground swell, but were not dominating factors.

Several months after the Kalkaska schools closed early in 1993, the Republicans and Democrats were trying to outdo each other on promising property tax relief. Democrats proposed to abolish local property taxes as a source of funds for local schools. The Republicans upped the ante by agreeing and linking it to their own school reform agenda.

Engler signed a bill in August 1993 throwing out property tax funding of schools — a frighteningly radical move for a state that relied on such taxes for almost two-thirds of school funds. Furthermore, the bill passed even though no alternative funding was in place. More modest descriptions likened the move to jumping out of an airplane without a parachute or jumping off the high dive without checking to see if there is water in the pool.

Engler, who in his 1990 campaign had promised to slash property taxes by 20%, knew that sentiment against the property tax was high. Ever the shrewd politician, he linked his anti-tax rhetoric to attacks on what he called “the wasteful, inefficient, educational monopoly.” Increased state funding, he promised, would allow his administration to “control the money, and use it to smash the school bureaucracy, finally forcing a solution to our failed public education system.”

In the fall of 1993, Engler’s promises of school reform and tax relief were a winning combination. Reform of school financing passed before year’s end, along with legislation on charter schools and increased state standards and testing.

Under the governor’s proposal, the local property tax would be replaced primarily by an increase in the state sales tax, from 4% to 6%. Under the Michigan Constitution any sales tax increase has to be approved by voters, and the showdown was set for March of 1994. Engler pushed hard for the sales tax package. Under the finance reform legislation, if the referendum failed, the increased state funds would come primarily from a hike in income taxes — a fallback supported by the Michigan Education Association and the Michigan Federation of Teachers. On March 15, 1994, Michigan voters, by a roughly two-to-one margin, rejected the income tax hike and approved the 2-cent increase in the sales tax. In politics, where perception matters as much as substance, the vote was seen as a stunning victory for Engler.

“Engler just ran circles around the MEA, politically,” Plank said. “Partly this is because the governor is a very good politician, and partly it is because the leadership of the MEA was accustomed to having a great deal of power. They became complacent — not only about their power, but also about their virtue and being on the right side of the issue.”

The reform’s biggest effect was on local property taxes — which were reduced but not eliminated, as originally promised.

Before the reform, approximately 60% of the school funding came from the local property tax. In the 1994-95 school year, only 19% of school funds came from local sources, according to an analysis of the reform by C. Philip Kearney of the School of Education at the University of Michigan. Approximately 75% came from the state, and 6% from the federal government.

Although the state monies are provided primarily by the increased sales tax, property taxes have not been eliminated. The final package implemented a state tax on all property — the first ever — and a local tax on “non-homestead” property such as rental property, second homes, and commercial and industrial property.

Together, the state and local property tax account for roughly 30% of school funding. In addition, the cigarette tax was increased from 25 to 75 cents, and other taxes were imposed such as a tax on property transfers.

Observers underscore that Michigan did not base its reform on a tax cut, but merely a tax shift. But the public, whose anger had been focused on property taxes, viewed the change as tax relief. “Engler got credit for a tax cut without really cutting taxes,” notes Labaree. “That’s a perfect political position to be in.”

Even more astonishing to some was Engler’s willingness to embrace increased school finance equity in exchange for the legislative votes needed for his “tax cut” package.

In essence, the Michigan finance reform quickly raised spending for the lowest- spending districts, kept the middle-spending districts about the same, and reduced increases for the highest-spending districts. But while inequalities were reduced, there is no proposal to eliminate them. “The difference between the top and the bottom will not be as severe, but it will be maintained,” notes Disbrow. “The poor will stay poor and the rich will stay rich, relatively speaking.”

Under the finance reform, the legislature guarantees a basic per-pupil allowance for each district, known as the foundation grant. In addition, a district may receive additional funds known as categorical aids for “at- risk” students, special education, transportation, bilingual education, and so forth. The foundation grant for low-spending districts was immediately raised to $4,200. The foundation grant for schools in the middle range of $5-6,000 did not change significantly. Further, the state decided not to “level down” high-spending districts as long as voters were willing to levy additional local property taxes.

A look at some individual districts helps clarify the complicated situation. In the 1993-94 year, the Onaway district in rural Michigan had a per-pupil revenue of $3,277. In the 1994-95 school year, its foundation grant was brought up to the minimum of $4,200, for a 28% increase. In the affluent suburban community of Bloomfield Hills, the 1993-94 per-pupil revenue was $10,358. In 1994-95 it rose 1.5% to $10,518. By the 1999-2000 school year, Kearney estimates that Onaway’s per pupil spending will be $6,083. The per pupil spending for Bloomfield Hills will be $11,601.

The foundation grant is not the entire picture, however. As part of the political deal-making that accompanied the reform, representatives of urban districts successfully pushed a measure that provided an additional 11.5% in funding to medium- and low-spending districts for children receiving free federal lunch. Thus Onaway, on top of its foundation grant, received an additional $173 per pupil in such “at-risk revenue” in 1994-95. “We fought hard for the additional at-risk monies, and it was a real victory,” says Michael Boulus, executive director of the Middle Cities Education Association representing 26 urban districts other than Detroit.

The main beneficiaries of the overall finance reform, however, were the rural districts at the bottom of per-pupil spending and not the urban districts, which tended to be in the middle of per-pupil spending. “The majority of the Republican leadership are not urban, they are rural legislators,” notes Eleanor Dillon, political and legislative director for the Michigan Federation of Teachers. “And so they were looking after their own.”

New Controversies Erupt

After the funding reform issue was settled, many educators hoped for a period of stability and an end to the education wars. But it was not to be. Just as the November elections caused a political shift nationally, Michigan politics took a turn to the right.

Three interrelated issues are involved in the current education controversies: the School Code, a 40-year-old set of regulations passed by the legislature and strengthened during the funding reform package; the development of mandatory state standards embodied in what is called a core curriculum; and state accreditation of schools based primarily on a series of standardized tests in the 4, 7, 8, and 11 grades, known as the Michigan Education Assessment Plan, or MEAP.

Political developments in November set the stage for the controversies. First, Engler was overwhelmingly re-elected, thus fueling his national ambitions. Second, Republicans gained control of both houses of the Michigan legislature. Third, members of the radical right, which has ties to the Christian fundamentalist right, won elections to the State Board of Education. A 7-person body, the board is selected through statewide at- large elections, not by region. Overall, the trend was clear: the Republicans were dominant and could push their agenda without input from Democrats and their largely urban supporters.

In education, the developments also exposed differences between business interests and more conservative activists, the two key forces in Engler’s base.

The corporate community had been integrally involved in the issues of state standards and accreditation. It followed the dictum that those who pay the piper set the tune. So if the state was going to pay for the bulk of school costs, the corporate community expected higher state standards and oversight. But the radical, more libertarian right has a different agenda.

One indication of the radical right’s aggressiveness was the State Board of Education’s adoption of a new vision statement in January. With several references to God, religion and “the marketplace of a free society,” the document sent notice that the formerly pro-forma State Board of Education intended to play a key policy-making role and use the levers of state government to push its anti-government agenda. Coinciding with the new vision statement was Engler’s State of the State speech, in which he called for a repeal of the state School Code governing everything from length of the school year, to teacher certification, to curriculum standards. He proposed that the state code be replaced by a local Education Code under the rationale that, “It’s time to stop controlling education from Lansing or Washington. It’s time to start transferring full authority to parents and the schools they pay for.”

Engler’s call was seen as an endorsement of the radical right’s education agenda and an attempt to use Michigan’s education reform to propel him into the national limelight and a possible run for the vice presidency. “Right now, Governor Engler is focusing beyond Michigan,” observes Michael Bitar, superintendent of Battle Creek. “And if you want to play on the national scene, you’d better be in with that strong fundamentalist, strong conservative group.”

The School Code is anathema to the radical right for several reasons. One is that it contradicts their anti-government, local control ideology. Second, it potentially undercuts the ability to establish highly deregulated charter schools. While the charter school movement includes diverse elements in Michigan, one of its main forces has been the Christian right. Christian fundamentalists, for instance, have consistently tried to establish a network of Christian homeschoolers as a charter school.

“A lot of this is about choice, charters, and vouchers,” notes Boulus. “A deregulated school code makes it easier to implement some of these charter schools.”

Related to the School Code is the proposed mandatory core curriculum that local districts are to have in place for the 1997-98 school year. The core curriculum is in some ways a misnomer; it is actually a set of learning objectives and academic outcomes set for math, science, reading, history, geography, economics, American government, and writing. Local districts would still determine what textbooks, materials and teaching methods would best reach the objectives.

Clark Durant, an attorney who is the newly elected head of the State Board of Education, wants the core curriculum to be voluntary. He stresses that parental choice and marketplace forces should be the guiding philosophy in education. A Republican from the affluent Detroit suburb of Grosse Pointe, Durant has a long history of involvement in national Republican politics and is known as a sophisticated political operator.

The radical right’s opposition to the core curriculum appears to be based both on the idea of a state standard and the standards’ content. Some Christian fundamentalists, for example, charged at public hearings that the standards inadequately stressed phonics and grammar and did not include creationism. Others were upset that the standards downplayed the literary canon and overemphasized cultural diversity and independent thinking skills.

“Critical thinking is educationese for teaching values and beliefs,” charged Rep. Alan Cropsey (R-DeWitt), who after the fall elections became chair of the House-Senate Administrative Rules Committee that must approve the standards. “If it means teaching kids to logically solve problems, that’s fine. But if that means teaching kids to question their parents’ values, that’s not fine.”

Several observers note that while the business community had pushed standards, it left a fair amount of leeway to educational groups on content as long as there was increased testing to measure achievement. Bitar, superintendent of Battle Creek, expressed the frustration of a number of administrators who worked hard, and not always comfortably, with the business community to develop standards. And now that this once-settled issue is up for grabs, many district officials are not only confused but angry. “The ultra-conservative push is in contradiction to what business tells us they want,” Bitar said.

The big question is whether the business community and the legislature will go along with the radical right’s attempt to jettison mandated state standards and to repeal the School Code.

The legislature, which over the years developed the School Code and strengthened it during the 1993 reforms, does not appear likely to follow Engler’s lead and scrap the code, according to most observers. But more moderate legislators don’t appear to have the votes to mandate the state standards, and the radical right will probably win on that issue. The business community, meanwhile, has been noticeably reluctant to enter the controversy. “The business community made curriculum and testing its priority for 15 years,” notes Plank. “But the governor seems to have given education issues to the right and is trying to placate the business community with tax cuts and economic development issues.”

There are also those who suspect that the business community isn’t really sure what it wants when it comes to education — that it is torn between the appeal of deregulation and its concern that the state hold schools accountable for how well they spend state money. “Quite frankly, the business community doesn’t have its act completely together,” said one observer. “And just as frankly, they are already getting their money’s worth from the schools, given that they are only offering kids $5-an-hour jobs.”

Michael Usdan, president of the Institute for Educational Leadership in Washington, D.C., notes that the Michigan controversy over standards reflects a national dilemma. In 1989, for only the third time in U.S. history, a president convened governors for a single issue — this time on education.

Following that gathering, a bipartisan consensus was forged on the need for standards and goals, a consensus that can be seen in the overwhelmingly similar perspectives of America 2000 under President Bush and Goals 2000 under President Clinton.

But now the very concept of national goals and standards is under attack from the radical right, and for what progressive educators would generally consider the wrong reasons. “What scares me more than anything else is the mindless, anti-government bashing that is going on,” observes Usdan. “There’s a mean-spirited rhetoric out there.”

The third piece to the current controversies is state accreditation of schools. When the state began to accredit schools this year, 145 schools were summarily accredited, 3,000 were given interim accreditation, and 89 received no accreditation. The accreditation was based primarily on the standardized MEAP tests. If schools go for more than a year without any accreditation, they can potentially lose 5% of their state aid.

The accreditation has come under criticism, particularly from local administrators who must administer the MEAP test and who believe it is a poor indicator of how well a school may be doing.

Arthur Wright, principal at the Holmes Middle School in Flint that includes seventh and eighth grade, notes that his school failed accreditation and thus its state funding may be reduced in coming years — even though the test was given to seventh graders who had only been at Holmes for four to five weeks. He believes the tests will inevitably hurt urban schools because like all standardized tests, they tend to be biased against low-income and minority students. Nor does he understand the logic that would reduce funds to schools needing help. “If a school’s behind, the state should be giving them more money, not less, to catch up,” he says.

An analysis by the Detroit News this spring showed that schools earning state accreditation tended to be smaller, paid their teachers better, and spent more per student. Tom Lukshaitis, president of the Sandusky Education Association, noted that 111 of the 145 schools receiving accreditation were from the state’s wealthier districts.

Missing Perspectives

One troubling aspect in the Michigan situation is the lack of input from forces representing the African-American community. “The grass-roots organizations, the Urban League, the NAACP — those kind of agencies have not been heard from in this debate, at least on the statewide level,” notes Plank of Michigan State University. “And that’s where the action is these days. So it’s a striking absence.”

African-American groups and educators seem to be putting their energy into developing schools that meet the needs of African-American children, both in terms of private schools, schools within the public system, or charter schools. African Americans and other minority groups, for example, are taking advantage of Michigan’s charter school legislation to set up new schools. Of 31 charter schools tentatively approved by Central Michigan University this spring, for example, seven are designed to serve African-American students; some specifically note they will have an Afrocentric curriculum. Another charter school hopes to cater to the Armenian population in Detroit, and one in Saginaw is to serve Latino youth. Under Michigan’s Law, universities may issue a statewide total of 75 charters.

The charter school movement has had a controversial history in Michigan. The original charter bill passed during the fall of 1993, along with legislation on the finance reform and increased standards and testing. But the original charter legislation was so highly unregulated that even the governor’s supporters worried about its constitutionality. Critics argued that the charter school law was little more than a thinly disguised attempt to funnel public dollars to private schools. A Michigan Circuit Court judge threw out the charter school law last fall, and the matter is before Michigan’s Court of Appeals.

New legislation that took effect this spring set up stricter guidelines for charter schools. The MEA joined the suit against the original legislation, but has not challenged the new law, according to Cynthia Irwin, a staff attorney for the MEA. Although the new law allows non-union charter schools, it explicitly permits charter school employees to organize. It also requires that charters meet the State Code and establishes increased public accountability.

Irwin argues that Engler has portrayed the MEA as defenders of the status quo in part to mask the radical right’s agenda of trying to bust up the public schools system. The governor and the MEA are long-term enemies, Irwin agrees, but there are strong political reasons for that.

“Having a difference of opinion with the governor does not necessarily mean you are defending the status quo,” she notes.

There is little doubt that Engler and the radical right want to do more than open up the public school system in order to save it.

Durant, who ran for the State Board of Education in November at Engler’s prodding, told Rethinking Schools that one of his biggest complaints about public schools is that “they are essentially controlled by some government body.” Durant consistently sprinkles his conversation with business and marketplace analogies — referring to customers instead of students, for example, and extolling the virtues of “real competition.” Like many conservatives, he uses populist rhetoric of choice, parent empowerment, and freedom from monopoly to argue for his views.

Michael Warren, a 27-year-old conservative lawyer recently hired by the State Board of Education to draft new rules and regulations for the public schools, has added some substance to the logic of Durant’s rhetoric. In a seven-page report to the board this spring, Warren called for schools to become public education “corporations” owned by “shareholders.” He presumes, he wrote, that these corporations would “hire a CEO, CFO, a COO and be governed by a Board of Directors.” Further, the corporations would be free to establish their own curriculum, hours, graduation requirements and, most tellingly, their own admission requirements. “Some schools would be college prep, some vocational. Some would be academies for the gifted, others for the challenged,” he wrote.

It is precisely such an unregulated, elitist, corporate mentality that sends chills up the spine of many public school teachers and administrators — urban, rural, and suburban. Up in Kalkaska, for instance, high school principal Stafford Wood is hundreds of miles from the politicking that goes on in the capitol of Lansing. But he doesn’t think one needs a Ph.D. in political science to read between the lines of the radical right’s agenda. “Where are we headed today? If we continue, I think you could probably see the demise of public education,” he argues.

What Does It All Mean?

For progressive educators, it’s particularly hard to evaluate the emerging split between the radical right and the business community — and whether and how to take sides. Many who question the value of state-imposed standards and worry about increased use of standardized testing are reluctant to appear to be siding with the radical right.

“The complexities of the issues are astonishing,” notes Labaree. “It’s very hard to find a good, principled position to fight for. You have the business community, which says cut taxes yet we want standards and we want efficiency. And then you have the Christian right, which is increasingly anti-public schools in general.” The education controversy in Michigan also highlights a broader problem facing progressives, Labaree notes. “It’s the politics of the 1990s. Who do I align with: David Kearns or Ralph Reed?” Kearns is a former IBM executive and assistant Secretary of Education under President Bush. Ralph Reed is head of the Christian Coalition.

Labaree’s hope is that that split between the business community and the radical right becomes so intense that they will be unable to come together around issues and candidates — thus providing an opening for a more progressive perspective.

Plank also finds uncomfortably few options for progressive educators, at least in the statewide policy debates. He is most worried about the radical right’s agenda. “The business community’s conceptions of what schools are for is very narrow, but at least they are concerned with maintaining minimum standards and getting young people to the point of employability,” he says. “Those are not the concerns of the Christian right. It’s an uncomfortable position for progressives, but tactically it may be where we are at. The business community’s agenda is much closer to a progressive agenda than the fundamentalist agenda.”

Plank argues that on policy issues, progressives have to work harder to develop an independent stance. Because of the potentially reduced role of local school boards due to the increase in state funding and planned increase in state standards, questions of how to nurture genuine democratic control of schools are especially pertinent. One possibility for progressives, Plank says, is to focus on local and district governance and to organize for schools that better meet the needs of children and community. This might be particularly useful in Michigan, he said, which does not have a strong tradition of innovations involving site-based management and decision-making. “I don’t think we are going to go back to large, top-down bureaucratic systems,” Plank says. “We can either regret and lament that, or take advantage of the spaces being opened up.”