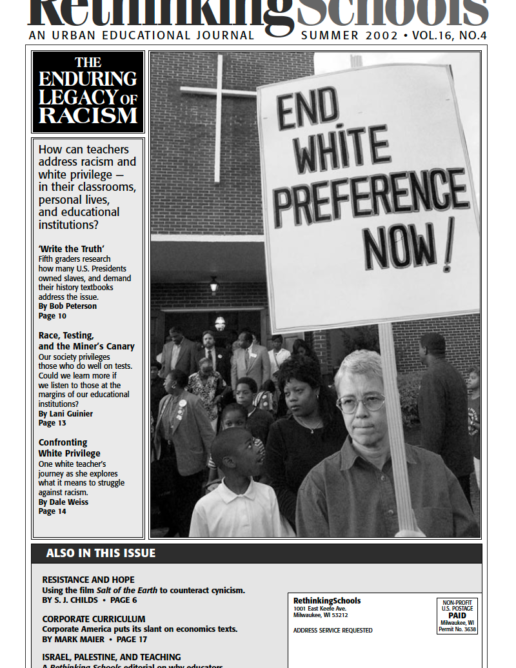

Let Them Eat Tests

Bush's new education bill ushers in a new era in the federal role in education — a conservative one that could hurt poor schools most.

Stock up on number 2 pencils. That may be the only sure advice to follow in the wake of new federal education legislation signed by President Bush earlier this year. More standardized tests are on the way, and they carry “high stakes”-and high hurdles -with them.

Perhaps even more significant is how the legislation could reshape the federal government’s historic role as a promoter of access and equity in public education in the service of a conservative agenda that comes wrapped in rhetorical concern for the poor and people of color, but which may ultimately hurt poor schools most.

Essentially, the legislation codifies at the national level policies that have already wreaked havoc at the state level: punitive high stakes testing, the use of bureaucratic monitoring as the engine of school reform, and “accountability” schemes that set up schools to fail and then use that failure to justify disinvestment and privatization. It’s George W. Bush’s dubious “Texas miracle” gone national. (For a detailed discussion of Bush’s Texas education record, see Rethinking Schools Fall, 2001, and Summer, 2000.)

MANDATED TESTS

Federally mandated annual testing is the cornerstone of the comprehensive, bipartisan bill that reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), a consolidation of the major K-12 federal education programs including the Title I program that reaches 47,000 high-poverty schools. The tests are central to a greatly expanded and revised role for the federal government in local schools and districts.

The bill’s far-reaching implications are just now coming into focus, despite the high-profile attention Bush gave to education issues during his campaign. The euphemistically named “No Child Left Behind Act” passed with overwhelming Republican and Democratic support, 381-41 in the House, 87-10 in the Senate. Two Senators, Kennedy (D-MA) and Gregg (R-NH) and two Representatives, Boehner (R-OH) and Miller (D-CA) were largely responsible for crafting the legislation, bypassing in significant ways some of the usual advocacy input, deal-making and compromise that normally raise alarms about dramatic shifts in federal policy.

Among the major features in the law, which runs over 1,000 pages:

- Mandated annual tests in reading and math from grades 3-8 and at least once in grades 10-12.

- Additional annual tests in science beginning in 2007, given once between grades 3-5, 6-9 and 10-12.

- Use of these tests to determine whether schools are making “adequate yearly progress” towards 100 percent proficiency for all students within 12 years (2013- 2014).

- Sanctions for schools receiving federal Title I funds that don’t reach their “adequate yearly progress” goals, which most likely will be impossible to meet (see below). The sanctions include now-familiar “corrective measures” like outside intervention by consultants, replacement of staff, or state takeover. Additional sanctions reflect the administration’s privatization agenda that lurks just below the surface of the legislation. This includes use of federal funds to provide “supplemental services” to students from outside agencies, imposing school choice or charter plans, or transferring management of schools to private contractors. Tenure reform, merit pay, and teacher testing are also potentially in the mix, though they are not mandated by the new law.

What’s significant about these policies is not so much their content – they are neither new nor promising as school improvement strategies – but their federal endorsement and political packaging. This rightward turn in federal education policy comes linked to Bush’s trademark “compassionate conservatism.” As in Texas, it includes a rhetorical attack on the “soft bigotry of low expectations” and purports to focus attention on the real crisis of school failure in many poor communities. The law targets more federal money to the poorest schools, and mandates dramatic changes in testing and reporting requirements that will focus attention on the racial dimensions of the achievement gap, the learning needs of new English language students and students with special needs, and the widespread use of underqualified and uncertified teachers.

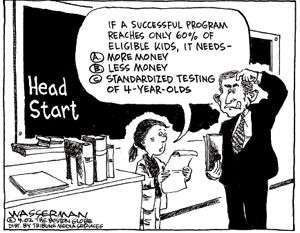

But while the legislation turns up the spotlight, and the heat, on low-performing schools, the remedies it offers have proven ineffective, even harmful. Furthermore, the extra dollars, an additional 18 percent or about $3.5 billion more for ESEA programs, are already threatened by the administration’s “war budget” – which calls for eliminating 26 of the federal programs just reauthorized in the new ESEA. The legislation still doesn’t provide full funding for Title I, which currently reaches less than half of all eligible low-income students. In fact the gap between the bill’s lofty goals and its low-rent resources suggest its proper title would have been, “The Unfunded Federal Mandates Bill.”

SIMPLE-MINDED APPROACHES

Educationally, the bipartisan approach behind the new federal legislation is both simple and simpleminded. Thanks to two decades of Governor’s education summits and the persistent urging of the Clinton Administration, virtually all states have adopted new curriculum standards. They are now being directed to enforce these standards through annual tests or face losing federal funds. Public reporting of scores is designed to identify schools and students that are not “proficient,” while highlighting gaps between genders, races, and other subcategories (special education, new language learners, poor students, etc.)

All districts and states are required to plot a path from current levels of achievement to 100 percent proficiency within 12 years (theoretically, in steady, equal steps forward). “Annual yearly progress” goals will be set for districts, schools and individual subgroups. Any school or district that doesn’t meet all its goals for two consecutive years will be put in the “needs improvement” category, and if they are receiving Title I money, will face an escalating scale of “corrective action.” (The “corrective” steps are mandated only for highpoverty schools receiving federal Title I funds, though states are directed to develop their own sanctions for other schools).

PREDICTABLE EFFECTS

It’s fairly safe to predict the effects of this scheme as it mirrors the standardized testing plague that swept states in the 1980s and 1990s. Test preparation will dominate classrooms, especially in struggling schools, and curriculum focus will narrow. Already, for example, some states are de-emphasizing social studies because history is not one of the federally mandated measures. Statistical “accountability” to bureaucratic monitors from above will take precedence over real accountability to students and their communities, and the huge resources poured into testing programs will do nothing to increase the capacity of schools or districts to improve their educational services.

The culture of testing in schools will be strengthened in many ways. The legislation requires that 95 percent of all students participate in the mandated assessments. While this will challenge the common practice of boosting scores by excluding large numbers of students from the testing pool, it will also increase the pressure that has led to cheating scandals and to grade retention policies that push students out of school.

The “adequate yearly progress” formulas mandated by the new legislation are so convoluted and unrealistic they seemed designed to create chaos and new categories of failure. An April 3 survey in Education Week suggested that as many as 75 percent of all schools – not just high-poverty Title I schools – could be placed in the “needs improvement” category.

“It’s going to really be a nightmare for states,” Cecil J. Picard, the superintendent of education in Louisiana, told Education Week. He estimated that as many as 80 percent of Louisiana schools would fail to meet the targets. Wyoming officials predicted over half would fail. In North Carolina, a state that is frequently cited as an example of the progress that standards and testing can bring, one researcher calculated that only about 25 percent of all elementary schools would have met the new standard if it had been in place over the past three years. The Rhode Island Dept. of Education concluded that there was “virtually no school in the state over the past four years that would actually meet that kind of criteria.” Had these standards been in effect while Bush was running for President as an education leader, Texas would have been high on the list of failing states.

Making the new system operational at all will be a bureaucratic horror show. State curriculum standards are barely in place and vary widely from state to state. While the new federal law directs states to use the current school year to set baseline levels and begin imposing sanctions next fall, many states have not yet even created tests for their new standards.

The new law appropriates about $400 million each year for the next six years to develop new tests. But, according to estimates reported in Time magazine, “Full implementation of the Bush plan, with highquality tests in all 50 states, could cost up to $7 billion.” No wonder an executive of one of the major testing firms responded to Bush’s proposals last year by declaring, “This almost reads like our business plan.”

The law explicitly mandates tests that attempt to measure progress in meeting state curriculum standards, as opposed to the more commonly used general knowledge exams. Only nine states currently give annual tests tied to their standards. One testing expert, Matthew Gandal, writing in a discussion paper for the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, estimated that the new law would require the creation of “well over 200 new state level tests” and force most states “to more than double the number of tests they are now giving.”

Such an explosion of testing will severely tax the capacity of the $700-million-a-year testing industry currently dominated by four major testing firms – including McGraw-Hill, with close Bush family ties (see the Jan. 28 Nation article by Stephen Metcalf, “Reading Between the Lines.”) As Gandal noted, “The normal cycle for creating a new assessment in just one state is 2-3 years. This now needs to happen in two subject areas in at least 34 states.” Inevitably this will lead to poor quality tests, even by the industry’s dubious “scientific” standards. Some states are already seeking to add a few “standards-based” questions to the off-the-shelf products they now use as a relatively cheap and easy, if unreliable, way to meet the new mandate.

The legislation provides for a “negotiated rule-making process” to encourage states to get the new system up and running despite the host of quality and implementation issues that have been raised. But as far as the basic framework of the plan is concerned, “There’s not much to negotiate,” said Susan B. Neuman, the assistant secretary for elementary and secondary education. The Boston-based advocacy group FairTest has pointed out that the language of the law does allow room for better, classroom-based assessment processes, but the Department of Education’s implementation regulations specifically emphasize standards-based testing. FairTest concludes, “States which seek to use high-quality, largely local assessments, particularly if they will use classroom-based assessments and portfolios, will have to struggle to use these assessments.”

“The bottom line,” says Scott Marion, the director of assessment and accountability for the Wyoming education department, “is that we’re going to end up identifying, by any stretch of the imagination, incredibly more schools than we believe the resources are there to serve.”

NEW CATEGORIES OF FAILURE

An obvious question is why would the federal government adopt narrowly prescriptive strategies that will label huge numbers of schools as failures on the basis of test scores? This is a far cry from the historic tradition of federal intervention on behalf of racial equity, inclusion for students with disabilities, or equitable distribution of resources. It is also a major reversal of traditional rhetoric about “local control” of schools and reflects the larger political agendas that are in play.

Conservatives are not blind to the likelihood that this test and label strategy will lead to a large number of Fs on the new school report cards. For example, conservative critic Abigail Thernstrom, who sits on the Massachusetts State Board of Education, declared “Getting all of our students to anything close to [proficient] is just not possible. It’s not possible in Massachusetts or in any other state. … Neither the state nor the districts really know how to turn schools – no less whole districts – around. . I don’t know how we’re going to have effective intervention within the public school system as it’s currently structured.”

“As it’s currently structured” may be the key phrase. The new federal law is a compromise between rightwing and centrist political forces in Washington that links an increase in federal funding to a narrow vision of school improvement based almost exclusively on state standards and tests. The funding increases are not enough to make dramatic improvements in conditions of teaching and learning in poor schools, especially with economic recession feeding a new round of state and local cutbacks and federal dollars still providing only about 7 percent of all school spending.

When this new federal testing scheme begins to document, as it inevitably will, an inability to reach its unrealistic and underfunded goals, it will provide new ammunition for a push to fundamentally “overhaul” and reshape public schooling. Conservatives will press their critique of public education as a “failed monopoly” that must be “reformed” through market measures and steps towards privatization. If, as many expect, the pending Supreme Court decision on vouchers endorses the transfer of state and federal dollars to private and religious schools, it will further feed this trend and give greater momentum to the rightward turn in federal education policy.

The ideological bent of the new law is evident even in its relatively benign programs, like those promoting teacher quality and increased reading instruction. While attention to these two areas has generally drawn broad support, the specific provisions of the legislation echo problems in other areas.

THE NEW LAW’S MANDATES

The new law mandates that all teachers be fully certified and licensed in their teaching areas by June 2006. It also requires all paraprofessionals to have at least two years of college beyond high school or pass a “rigorous” local/state exam. New hires must meet these provisions immediately, while existing staff have several years to comply. As with the “adequate yearly progress” goals, however, there is near universal acknowledgement that these goals cannot be met, particularly given current levels of underfunding.

Most states already have similar teacher licensing requirements on the books, but can’t find enough qualified candidates due to low pay scales, rising enrollments, and other aspects of the well-documented teacher shortage. Finding fully qualified teachers is especially difficult in rural and poor schools, and in some subject areas, like math and science. But while Bush has been barnstorming the country in front of signs proclaiming “A high quality teacher in every classroom,” his latest budget proposes a freeze on new spending for teacher-quality programs, despite the new federal mandate. He’s also proposing the elimination of related programs such as the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards and technology training funds. Similarly, the Eisenhower Professional Development funds, which helped prepare math and science classroom teachers, have disappeared into a block grant program where they will compete with class size reduction and other priorities. The changes “virtually eliminate dedicated federal funding for K-12 math and science education,” Education Week reported.

Currently employed paraprofessionals, who in many Title I schools represent a significant presence of community members working for the lowest pay, face the prospect of having to complete two years of college without new support. The law requires that a portion of Title I funds be set aside to help teachers meet the new certification requirements, but a similar set-aside for paraprofessionals was made optional.

Even reading instruction is ideologically framed. The new law puts over $1 billion into expanded reading, literacy, and library programs designed to help every student read proficiently by 3rd grade. These programs will support needed professional development for teachers and provide materials to promote essential literacy skills. But the effort is linked to dubious language restricting funding to “scientifically based reading programs,” which may be narrowly interpreted to endorse only certain phonics-based approaches or commercial reading packages. More damaging is the legislation’s wholesale attack on federal bilingual education programs, which the new law recasts in the spirit, if not the name, of “English Only” intolerance (see James Crawford’s article, page 5). The new bill transforms the Bilingual Education Act into the “English Language Acquisition Act.” It will assess schools on the basis of the number of students reclassified as fluent in English each year and severely discourages native language instruction.

RIGHT WING NUGGETS

The bill is also littered with assorted right-wing nuggets, such as a provision preventing districts from banning the Boy Scouts from using school facilities because of their anti-gay policies, and a requirement that districts accepting federal dollars open their doors to military recruiters.

Education advocates looking for hopeful signs will, for the most part, have to look elsewhere. There may be some solace in the fact that state compliance with the new federal regulations is likely to be uneven and enforcement efforts by the Department of Education difficult. The 1994 ESEA legislation had similar, if less stringent, requirements regarding standards and testing that went largely unheeded. Historically, the Department of Education has been reluctant to impose significant penalties or withhold funds from states and districts.

On the brighter side, the burgeoning grassroots movement against standardized testing will almost certainly grow in response to this onslaught. Some schools may benefit from the increased professional development and reading programs, and in some places increased attention may translate into more support for effective school-based reform.

But most of the political and educational fallout from the Bush Administration’s first major initiative in federal school policy will be heavy and harmful. Nor will it be the last round. Next up for renewal is the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, itself a longstanding source of unfunded mandates and another battleground between federal promises and performance on issues of equity. If the ESEA renewal is any guide, education advocates will need to keep their noses firmly to the grindstone. In the Bush era, there is sure to be another test coming your way.