Justice and Equity

Powerful Ideas for Powerful Kids

Illustrator: Kathy Sloane

Photo: Kathy Sloane

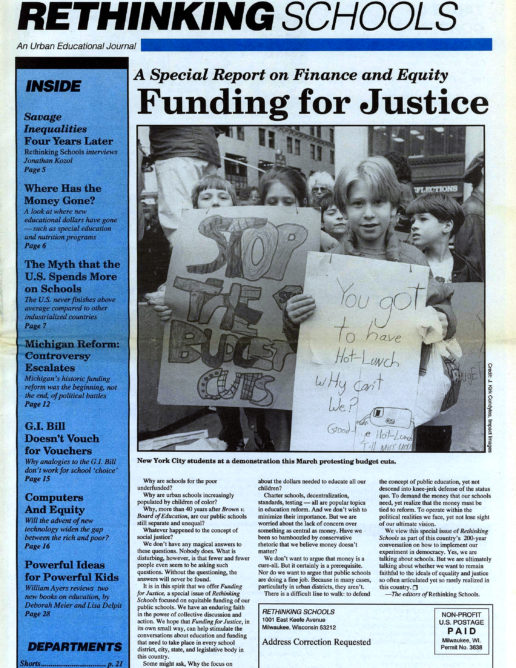

In the front row of a celebrity press conference called to announce a major financial gift to Chicago school reform sat five young men: Cornell Faust, Antwoine Conaway, Kelly Floyd, Derrhun Whitten, and Darnell Faust. Wearing starter jackets, gold chains, and earrings, and with elaborate designs carved into their short-cropped hair, they draped their long bodies over the folding chairs. “I’ll bet that’s Farragut’s fabulous five,” whispered a reporter, referring to the fabled dream team many believed were destined to become basketball champs this year.

When the young men were introduced fifteen minutes later, and stood with awkward adolescent smiles and waves, there was a gasp throughout the auditorium, followed by sustained and raucous applause. These were indeed state champions — 1994 Illinois State chess champions from Orr High School, a city public school that is 85% low-income and 95% African American. They had defeated New Trier High School from the wealthy gold coast suburbs to advance to the nationals, where they came in second by half a point to New York’s famous Peter Stuyvesant High School. Something in the contrast between the glib assumption about African American men and the actual accomplishment of these students made the ovation warmer and more moving.

The chess program at Orr is relatively new, initiated in 1986 by math teacher Tom Larson as a way to get his students to “sit still and begin using their thinking skills.”

Larson has a passion for chess linked to a deep belief in the capacities of his kids.

“My job is to guide them to independence,” he says. “To guide them through the process of maturing … I’m trying to build the dream. Faith, hope, and love.”

Faith, hope, and love — it’s a good starting point for teachers, and yet more is needed if we are to transform our schools into places of power and purpose. If we continue the current course, thousands of schools will go on malfunctioning as they uphold the tradition of cheating millions of kids out of an adequate educational experience. This failing tradition rests on the profoundly inequitable distribution of educational resources leaving most city schools starved and desperate (Orr High School, for example, spends six-thousand dollars per year per child; New Trier spends twelve-thousand); the existence of a range of tangled and self-interested bureaucracies sitting atop city schools, each capable of working its narrow agenda against any notion of the common good, and thereby rendering many schools lifeless places, hopeless and gutless; the presence of a culture of contempt for kids, distant from communities and families, deadening for students and enervating for teachers. If, on the other hand, we create the collective capacity to imagine a dramatically different world and summon the collective courage to sustain that vision as we work toward making that imagined world real, then we can begin to challenge these complex and interconnected causes of failure. It’s a tall order, to be sure, a complex matter of political will and social commitment to begin, but it is possible.

The late Ronald Edmonds, a researcher at Harvard University, long ago asked this penetrating question: “How many effective schools would you have to see to be persuaded of the educability of poor children?”

He went on: “If your answer is more than one, then I submit that you have reasons of your own for preferring to believe that basic pupil performance derives from family background instead of school response to family background … Whether or not we will ever effectively teach the children of the poor is probably far more a matter of politics than of social science, and that is as it should be.”

The crisis in the schools today is selective. There simply is no teacher shortage in Winnetka, while in Chicago we are desperate for qualified, outstanding teachers.

There is no huge command-style bureaucracy in Glencoe, while in Chicago its presence is unmistakable. And on and on: the crisis of school resources is particular; the crisis of school culture is specific; the crisis of school management is distinct.

Not surprisingly, this unnatural, selective school crisis is a crisis of the poor, of the cities, of Latino and African American communities. All the structures of privilege and oppression apparent in the larger society are mirrored in our schools: Chicago public school students, for example, are overwhelmingly children of color — 75% are African American, 25% are Latino — and children of the poor — half of the poorest children in Illinois (and over two-thirds of the bilingual children) attend Chicago schools. And yet Chicago schools must struggle to educate children with considerably less human and material resources than neighboring districts.

Illinois, like other states, has created two parallel systems — one privileged, stable, well-financed, successful, and largely white, the other disadvantaged in countless ways, disabled, starving, failing, and African American. When former Governor James Thompson called Chicago schools a “black hole” as he rejected appeals for more equitable support, he excited all the racial justifications and tensions inherent in that situation. And when a host of politicians issue of power, of whose voice gets to be heard in determining what is best for poor children and children of color.” She reminds us that if we want to enter that cross-cultural dialogue with a mind to learn as well as to teach, then we might struggle to embrace “the perspective that people are experts on their own lives,” to remember that people are rational beings and to be cautious, therefore, about accusing people of “false consciousness,” and “to be vulnerable enough to allow our world to turn upside down in order to allow the realities of others to edge themselves into our consciousness.” These are important lessons for teachers who would be successful with “other people’s children.”

Writing from Harlem

Deborah Meier writes from 30 years of experience as a city teacher and successful creator of innovative, small public schools in Harlem. She is a dreamer and a doer, a warrior for justice whose battleground is the hard surfaces of city schools. Her passion is democracy:

“There’s a radical new idea here — the idea that every citizen is capable of the kind of intellectual competence previously attained by only a small minority. It was only after I began to teach that public rhetoric even gave lip service to the notion that all children could and should be inventors of their own theories, critique other people’s, analyze evidence, and make a personal mark on this most complex world. It’s an idea with revolutionary implications.”

For Meier democracy is not the symbols of flag and anthem and statue, nor merely the formal granting of rights. Democracy pushes toward full participation in the life of a community — it is muscular, demanding, animated. It is also messy, sometimes inconvenient, always requiring thoughtfulness and vigor as well as the arts of tolerance and compromise. Democratic community is, for her, “the non-negotiable purpose of good schooling.” She argues that “schools embody the dreams we have for our children. All of them. These dreams must remain public property.”

Hers is an impassioned plea for the preservation of the ideal of public education as well as a practical plan to transform public schools into democratic communities of courage and learning. “Schools can squelch intelligence,” she says. “They can foster intolerance and disrespect. They affect the way we see ourselves. … [T]hat’s precisely why we cannot abandon our public responsibility to all children, why we need a greater, not lesser commitment to public education.”

Schools, she continues, are “examples of the possibilities of democratic community,” and that is partly why we struggle over content, vision, direction, and practical work. “Schools are the conscious embodiment of the way we want our next generation to understand their world and their place in it.” Schools must, then, be places where democracy is practiced and not merely talked about — places where people seek knowledge from evidence, find their own voice and attend to the voices of others, debate matters of importance to themselves and their communities, link consciousness to conduct in their everyday encounters.

For Deborah Meier the strategy for creating the possibility of democracy in education involves a struggle to restructure large, impersonal schools into smaller units — schools within schools, for example, satellite schools, houses, or some forms of charters. The keys to this restructuring strategy are that teachers transform their roles from passive clerks in a large bureaucracy delivering the goods to inert students, to thoughtful, caring people with responsibility for every kid and authorship of their own teaching; that families and communities have voice and choice in the education of their children; and that students become active in an environment they can shape, build, and call their own. Meier argues that there are no big schools that educate all children well. To people who say, “Well, I went to a huge high school and got a terrific education,” her response is, “Certainly some kids do get a good education in a big school. But they tend to be the top 20%, in effect, attending a small school-within-a-school.” Small schools are not panaceas, she argues, but they do create the condition where success for all is possible. Small schools are necessary — but not sufficient.

“Good schools, like good societies and good families,” writes Meier, “celebrate and cherish diversity. Since we don’t know the ending ahead of time, life’s unpredictability is a given. After accepting some guiding principles and a firm direction, we must say ‘hurrah,’ not ‘alas,’ to the fact that there is no single way toward a better future. It’s the kind of work that must be done by people who don’t all like the same movies, vote for the same politicians, or raise their own kids identically … It’s worth arguing about, leaving room for lots of answers, and not being afraid to tell each other the truth.”

Like her colleague and mentor, the late Lillian Weber who would willingly explore problem after problem with teachers but never end the conversation without her signature challenge, “What are you going to do about it?”, Meier consistently injects a call to action: “The question is not ‘is it possible’ to educate all children well; it is rather, do we want to do it badly enough.”

An Unsettling Challenge

When Lisa Delpit published “Skills and Other Dilemmas of a Black Progressive Educator,” she asserted her voice powerfully on the issue of educating “other people’s children.” It was as if she had announced that the emperor had no clothes by pointing out that almost all the progressives and reformers in education were white. Here was a life and death struggle for the survival of the Black community and the agenda was being set almost exclusively by whites who often misunderstood or misled that community. Delpit’s was a call that could not be ignored, but which made white progressive educators uncomfortable.

Deborah Meier, a white progressive reformer, almost certainly found it challenging. In a letter to The Nation in 1990, Delpit refers to a meeting of the two:

“About a year ago, I was to make a presentation to the annual meeting of a group of progressive educators. Of the 70 or so people present, there was one other African-American woman. This group — composed of some wonderful and usually thoughtful individuals — was busily engaged in discussions about educating all students for a democratic society. One presenter gave an impassioned speech about the need to build alliances across classes, ethnicities, and cultural groups. Only the other African-American woman, a few others and myself seemed to be able to recognize how bizarre the scene was. These people, who thought of themselves as progressives and who diligently sought integrated education for their children, had apparently not noticed that they were operating in an elite little bubble as they attempted to develop means to educate “other people’s children.” They were discussing the issues among themselves, and the poor and “minority” communities they were concerned about had almost no representatives among their members.

“This scene, and the literally dozens of other similar ones I’ve experienced, led me to write those articles. I’m much less concerned about the specifics of instruction than I am about the nature of the relationships developed in education. Although there are significant exceptions, I know that many of the white educators I work with and sometimes truly like don’t have the slightest inkling about what people of color say about them and how they view their actions in the classroom. They have no idea in part because they have not asked, and in part because they have not truly listened when an unsolicited opinion has been offered. Consequently, they have been shocked and sometimes hurt when I write about the deeply rooted anger that many people of color feel toward them. My hope in writing was to show the need for dialogue, and to give people a base from which to begin.

“Thus, I am saddened when I feel that what I’ve written is interpreted as continuing the useless dichotomy about competing methodologies. If asked, I will continue to say that we need both process-and skills-oriented instruction. But what we need even more is to open up the dialogue about what we need to those from all the groups we need to educate. My hope for all educators is that they rid their eyes of their own cultural blinders to see, really see, the students in front of them. And that they learn to utilize the resources that parents and educators of color can provide to help destroy those blinders.”

These two books are a further development of that debate, and perhaps they can help us to understand some of the theoretical and practical bases of the contradiction between the approaches of these two important leaders. Meier’s life-work has been to educate “other people’s children” and she brings a wealth of practical experience and deep reflection to the conversation. Delpit is a teacher and parent who has observed and recorded the dangers, difficulties, and misdeeds that can infect cross-cultural teaching. Each is candid and courageous, dedicated and intense. Each welcomes a good argument, takes ideas seriously as guides to action, and takes practice seriously as a source of ideas.

When Delpit argues that parents are a key and under-used source of knowledge about students, Meier would, I imagine, vigorously agree. And when Meier describes in her journal excerpts the “thorny underbrush” of dealing openly with racial conflicts within the school community, Delpit could, I think, match her anecdote for anecdote.

Deborah Meier’s consistent use of the word “racism” to mean prejudiced ideas might provoke from Lisa Delpit a reminder that racist ideas rest upon a racist reality and a culture of power. Meier’s examples of parents’ misunderstandings of teachers’ motives would almost certainly incite counter-examples from Delpit.

Deborah Meier is too smart, too experienced, and too connected to make the crudest mistakes that might follow from a position that racism is a problem of ideology alone. But in less skilled hands this position can be disastrous. It can lead to a shirking of responsibility for changing the structures of oppression and privilege, or to a fascination with the process of change while ignoring the content. It can allow us to believe that the task of schools is to rescue students from their communities.

The angry and insistent Black parents become, then, an annoyance that has to be dealt with; the Black teachers are deemed backward and stubborn; the white teachers become self-righteous, patronizing, and ultimately backward.

Surely there is a better way.

We need to remember again and again that racism is indeed a bad idea, but it is an idea brought forth and sustained by an unjust reality. The bad idea is not its own source or self-reference. Fighting racism in the realm of ideas alone, without undermining the structures that give birth to those ideas, is a hopeless mission. Remember, for example, the relationship between two characters in the film version of Alex Haley’s Roots. The captain of the slave ship considers himself a Christian and a liberal, and he finds the transporting of slaves odious work. He is particularly appalled by the behavior of his first mate, a crude, unpolished fellow who regularly abuses the human cargo and taunts the captain for his squeamishness. In one particularly revealing encounter the captain, all worry and hand-wringing, implores the brute to treat the slaves a bit better, insisting that they are also human beings and God’s children. The first mate looks him squarely in the eye and responds with astounding lucidity: Of course they’re human beings, he says, and if we’re to profit from this we’d best convince them and everyone else that they’re dogs or mules, anything but human. With that the captain retreats into his ineffectual anguish.

The point here, of course, is that prejudice and the idea of inferiority based on race grows from and is fed by the need to justify and perpetuate inequality, domination, control, and exploitation. While discrimination and slavery go back to antiquity, chattel slavery based on race — that is the enslavement of an entire people and their transformation into commodities without any family, property, or rights whatsoever, bound for life and for generations to come — was the “peculiar institution” born in America of the African slave trade. Racism as a primary social and cultural dividing line is the legacy of that institution. It developed from a greed for profit and was achieved by deception and a monopoly of firearms, not by biological superiority, real or imagined.

In 1903, W. E. B. DuBois predicted that the problem of the 20th century would be “the problem of the color line.” As we approach the 21st century the problem of racism is more acute and entangled than ever. Leon Litwick, in his 1987 presidential address to the Organization of American Historians, notes:

“The significance of race in the American past can scarcely be exaggerated. Those who seek to diminish its critical role invariably miss too much history — the depth, the persistence, the pervasiveness, the centrality of race in American society, the countless ways in which racism has embedded itself in the culture, how it adapts to changes in laws and public attitudes, assuming different guises as the occasion demands.”

Racism is more than bias or prejudice, more than a few bad ideas floating around aimlessly — it includes the structures of privilege and oppression linked to race and backed by force, powerful structures that are the roots of prejudice. The endurance and strength of prejudiced ideas and values lies in their renewable life-source: the edifice of inequality based on color.

***

There is more, of course. Both Deborah Meier and Lisa Delpit are brilliant, vivid storytellers and practical reformers. Each offers insights and action plans on virtually every page. These books complement, reinforce, and build off of one another in a thousand ways: the importance of teaching as intellectual and ethical work, the sensitivity to community and family in the project of education, the finding and building upon the critical importance of human capacity in schools. These are crucial books, best read together — to help us all move to a better, more hopeful space. Faith, hope, and love.

Faith, hope, and love — we return to this essential and yet largely undervalued and under-examined stance for successful teachers. Of course faith, hope, and love can’t be easily researched or taught didactically or defended rationally. Still, with it all kinds of errors and missteps will be overcome; without it no amount of technical proficiency will ever be enough. Teaching is relational, and the teaching-learning relationship begins with irrational commitments. The message of the teacher is: you can change your life. We need to find new ways to keep that message alive, for ourselves and for our students, and to fight for an expanded space where it can be enacted.