Israel’s Hold on Palestinian Education

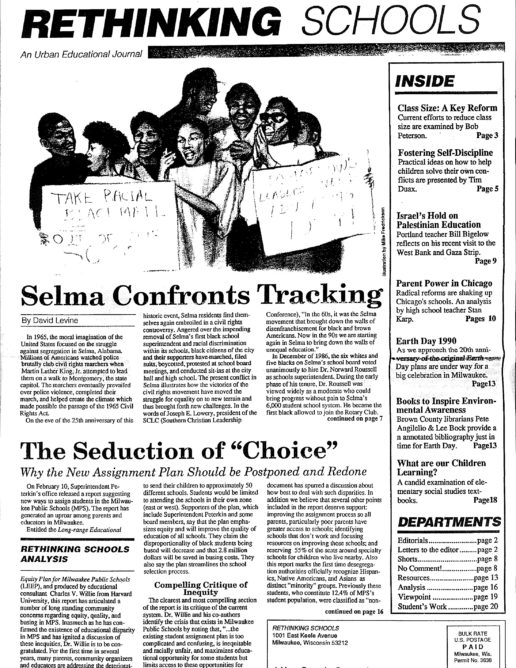

As I drove from Jericho to Jerusalem in the West Bank I saw my first Palestinian school. It was an unremarkable building – two stories, faded yellow paint, surrounded by dirt playing fields. But perched on top of the structure was an Israeli machine gun nest. Welcome to the West Bank, I thought.

For two weeks this past November and December, I toured the West Bank and Gaza Strip as part of an educators’ delegation sponsored by the Middle East Justice Network. Our charge was to investigate conditions for students and teachers in the Occupied Territories. The difficulty of this assignment soon became apparent: in response to the intifada — the Palestinian uprising — Israel had ordered all public and private schools on the West Bank shut. As well, for the past two years, all universities, colleges and even technical schools in the West Bank and Gaza have been forcibly closed. The only West Bank schools we were able to visit were kindergartens. Generally, the government has allowed these to remain open.

The closure of West Bank schools seems to have been carried out as a cat and mouse game by Israeli occupation authorities. In a tersely worded order, all schools—government, private, as well as United Nations operated—were closed “until further notice” on February 4, 1988. Could administrative functions be carried out? Could librarians continue to order and shelve new books? Could teachers meet with students off-campus? The military order didn’t specify, though the answer to these and other questions would turn out to be no.

In May 1988, schools were allowed to reopen but were shut again in July, then opened in December only to be closed in January 1989. This past school year for West Bank high school students lasted two and a half months and closed for a forced “vacation” in mid-November. As one parent we interviewed joked bitterly, “We have a summer vacation of ten months and an academic year of two months.”

Universities Remain Shut

On January 10th, the Israeli government allowed school to resume for most West Bank students, though “for security reasons” kept a number of schools closed. A few technical schools were allowed to reopen in February but all five major Palestinian universities remain shut.

The government claims it closes schools when they become “centers of unrest” and “centers of violent protest.” However, as a report issued by the human rights organization, al Haq, points out, Israeli justifications fail to account for “why all 1,194 West Bank schools were closed simultaneously without regard for activities at any specific location.” Nor does the government explain why kindergartners are not deemed security threats, but first graders are.

Educators and parents responded to the February 1988 closure by organizing informal tutoring sessions in people’s homes. Israeli authorities replied by outlawing all education outside of school. School administrators then encouraged parents to come to school to pick up homework packets for their children. Israeli authorities promptly outlawed homework.

The choreography of this Israeli-Palestinian struggle might be funny if its consequences were not so tragic. We interviewed Dr. Ahmed Baker, child psychologist and Birzeit University professor. “In my opinion, closing the schools constitutes a national criminal act,” he said. “I am worried that you are killing the cognitive development of 300,000 Palestinian children.”

“We now have thousands of eight year old illiterates,” a United Nations official told one reporter.

To a person, Palestinians we met spoke with pride about their educational accomplishments. “After the Israelis, we are the most educated in the entire Middle East,” one doctor in Gaza told us. “In Kuwait alone, there are 3,000 Palestinian engineers.”

Political Extortion

The Israeli government is exploiting this Palestinian reverence for education in a kind of political extortion. In essence, Israel is telling Palestinians, “If you want your children to be educated, and we know you do, stop the intifada.” Like so many of the actions of the Israeli occupation authorities—dynamiting and sealing houses, uprooting a village’s olive trees, confiscating property—the school closures are a form of collective punishment. Ironically, it’s a policy which implicitly recognizes the popular support for the intifada and the goal of Palestinian statehood, as every Palestinian is held responsible for the continued uprising.

But some Palestinians we interviewed felt that Israeli closed the schools simply to “keep us stupid.” This may be more than paranoia. The Israeli economy has no need for well-educated Palestinians. The Occupied Territories function as Israeli bantustans—reserves of cheap labor. The economy needs Palestinian dishwashers, gardeners and factory hands, not professors or doctors. The government must know that the thousands of well-educated but underemployed young Palestinians are likely to join the uprising with enthusiasm—and why educate future intifada militants?

Many Palestinians have channelled their outrage over the closure of schools into resistance. At a private school we visited in Ramallah, teachers meet regularly on school grounds in defiance of the military. As we spoke, parents arrived to pick up books and study materials for their children. Another day, as we showed up for lunch at the home of a university professor, students filed out of his apartment. He and his students risk arrest to maintain their studies.

Classroom Rebellion

And in those few months when schools were open, Palestinian students displayed a new spirit of assertiveness that some teachers found at once troubling and exciting. One West Bank high school teacher told of a confrontation with one of her classes. “I said we’re going to have a test. They said, ‘no we’re not.’ I said, ‘I’m the teacher and we’re going to have a test.’ A student stood up and said, ‘Miss, we rule the streets, we can surely rule this class.’”

The source of students’ classroom rebellion, she discovered, came from an awakened pride in their Palestinian heritage. “Students told me, ‘Miss, why do you teach us about 18th century Britain? We want to know about 20th century Palestine.’”

The school’s principal seemed enthusiastic about students’ resistance to school-as usual. “I try to negotiate with students,” she said. “The elected students association votes on demonstrations, calls teach-ins and show films. We give advice, but the final decision is theirs. They are more in control now.”

According to a recent Harvard Educational Review article by Khalil Mahshi and Kim Bush of the Friends Boys School in Ramallah, this student revolt is helping kindle a rethinking of the rigid exam-driven Palestinian curriculum. “Will high school students who have used the streets as classrooms be able to return to the old style of authoritarian education?” The writers ask rhetorically.

Already, informal neighborhood schools are experimenting with new teaching methods. In one class, a physics teacher taught lessons on electrical conductivity by discussing with students the dangers of removing Palestinian flags from power lines. Palestinian drama and music classes were added in some neighborhood schools. While new pedagogies and curricula are still in their infancy, it’s likely the young intifada activists will continue to challenge authoritarian teaching methods—when the schools are open—and thus stimulate ongoing educational experimentation.

Gaza Strip Gunfire

The Israeli government’s attack on Palestinian education is broader than the closing of schools and universities. Curiously, schools in vigorously nationalist Gaza, remain open. Nonetheless, restrictions on what can be taught are severe. As the director of Gaza College, a private secondary school, told us, “Let us not speak about freedom here. You cannot speak freely except about very trivial things. We are forbidden to teach about Palestine. No map that has the word Palestine is permitted. No mention of Palestine is allowed.”

At a U.N.-operated school in Shati Refugee Camp, the principal confirmed that it was forbidden to teach about Palestinian history. “Would a student be permitted to write an essay about one’s family history, where they came from?” one of us asked.

“No, it is illegal,” the principal replied. However, according to her, the biggest problem is not curricular restrictions but the Israeli army’s harassment of students. She complained of soldiers appearing at recess and when school was dismissed, provoking confrontations. Recently, the principal was beaten by two soldiers when she told them to leave after they assaulted an eight year old boy on the playground.

As if to underscore her point, after our first night in Gaza our delegation awoke in the morning to what sounded like gunfire. “They are firing tear gas into the school,” our host calmly told us. “This is very common.” When we returned to the school that afternoon, children greeted us at the gate with “rubber” bullets and tear gas canisters they’d collected that morning. When we entered the house our host told us that, an hour before, a child had been shot in the chest at the school as classes ended for the day.

Hospital officials we interviewed in Gaza, Jerusalem, Nablus and Jenin as well as human rights investigators in Jerusalem and Ramallah all confirmed that soldiers regularly surround schools and fire at students as they arrive or leave. One thirteen year old we spoke with in a Gaza hospital told us that he was shot during a twenty minute break as he mingled with friends in the school garden.

Some Israeli peace activists worry that the violence is taking its toll not only on Palestinians, but also on Israel itself. “The occupation is corrupting Israel,” said Rafi Greenberg, an American-born Israeli spokesman for Peace Now. “The very position of being master harms you. There used to be a lot of things attractive about Israeli life that just aren’t anymore.”

“I worry that Israel is in danger of becoming a lunatic state,” Gideon Spiro, founder of the Israeli veterans’ peace group, Yesh Gvul, told us. “We might become the Albania of the Middle East.” Spiro believes the $3.5 billion a year in U.S. aid supports the most militaristic tendencies in Israel and allows the government to maintain the occupation of Gaza and the West Bank without worrying about how to pay for it. In an article in the journal, News From Within, Spiro writes that as the U.S. continues to finance the occupation, “racism, discrimination and other policies resembling apartheid are growing and killing like a cancer the democratic cells of the Israeli society. The totalitarian methods and attitudes of the occupation dominate more and more the value systems of the Israelis.”

For their part, Palestinians appear unshakable in their determination to continue the intifada. School closures and other punitive measures have failed to suppress the uprising thus far because they do not address its root cause: the denial of a Palestinian homeland. Until statehood is achieved there appears little likelihood that Palestinians will abandon the intifada. As the director of Gaza College told us, “In the refugee camps, they say, ‘What have we to lose? Only our tents and our handcuffs.’”