How Should We Sing Happy Birthday?

Reconsidering classroom birthday celebrations

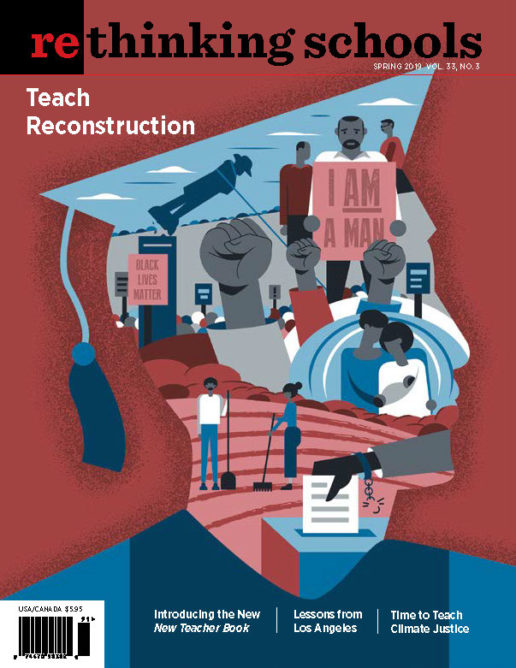

Illustrator: Olivia Wise

One morning last April, I was with my kindergarten students in our school’s cafeteria. I teach kindergarten and 1st grade — looping, with the same class for two years — at Central Park East 2, a public school in East Harlem, New York. I work with a paraprofessional named Vesna, who was also at the table. It was around 8 a.m. and the kids were eating cereal and bagels before we went upstairs to the classroom.

We often talk about birthdays in class, and in one of our discussions I shared that my birthday was coming up — a way to help us bond over a shared experience (“I have a birthday, too!”). A student named William remembered this information and turning away from his bagel with cream cheese, he said, “Kerry, we sing a different birthday song in our after-school.” He began singing it and two of his after-school classmates, Derrick and Fatima, joined in.

“Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you, happy birthdaaaaaay — happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you, happy birthdaaaaaay!” they sang, smiling and clapping to the beat. The song was familiar, but I couldn’t remember who wrote it. Later, I learned it was “Happy Birthday” by Stevie Wonder. Of course, this isn’t a generic birthday song, it’s a happy birthday song for Martin Luther King Jr., arguing that his birthday should be a national holiday. It sounded joyous — more joyous than the staid birthday song I had led children in singing every time we celebrated a student’s birthday: “Happy Birthday to You,” written by sisters Patty and Mildred Hill in the early 1900s. When I was growing up, that was the birthday song my white, English-speaking family sang; it was what I knew.

“Oh, wow!” I said. “Thank you for telling me!” William finished eating breakfast. Later, he told me he wanted to sing this song to me for my birthday.

That interaction at breakfast stayed with me for days. I remembered earlier in the year that William’s mom told me her son didn’t want to celebrate his birthday at school — only in after-school. At first I was puzzled; why not with us, with whom he spends six hours a day? Children seemed to like our birthday celebrations. Family members would often visit and share photos of the birthday child as the child was growing up. But seeing William happily sing the “Stevie Wonder version,” as we came to call this song, made me wonder if he wanted to celebrate his birthday in after-school partly because the birthday song they sang there — the way they celebrated his life and achievements over the last six years — felt the most happy and meaningful for him.

Then I remembered another moment earlier in the year, when I was reading aloud Alma Flor Ada’s I love Saturdays y domingos, a children’s book about a girl who speaks English and Spanish. Toward the end of the book, she has a birthday party with her family and they sing “Las Mañanitas,” a traditional Mexican birthday song. As I read the lyrics, a few students sang along.

My students are culturally and linguistically diverse. About two-thirds of the class is bilingual or have family members who are, and about two-thirds of my class are students of color. Many of my students’ families have roots in countries around the world, many of which of course have special birthday songs and traditions. Families who have lived in the United States for generations also celebrate birthdays in various ways. Each of my students’ families likely had special birthday traditions. In leading children to sing “Happy Birthday to You” at classroom birthday celebrations, I had been privileging my own cultural background over those of my students and their families.

For many children, birthdays matter. I needed to honor these days in ways that were meaningful and relevant for each of my students. So a few days after that moment at breakfast with William, I launched a birthday songs curriculum, inviting families to send in lyrics for birthday songs they knew so we could learn about them. I hoped this project would help children feel excited about celebrating birthdays in school. I also hoped it would be one of many ways to break Eurocentric norms in my classroom and help my students feel welcome and empowered.

22 Songs in Eight Languages

We started our study of birthday songs with a class discussion at morning meeting. At these meetings, which happen daily at around 8:30 a.m., we sing, greet one another, count the days we’ve been in school, and talk. To start our conversation that day, I asked, “What birthday songs do you know about?”

William raised his hand. “I know this one from after-school,” he said, and quietly sang, “Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you, happy birthdaaaaaay! Happy birthday to you, happy birthday to you, happy birthdaaaaaay!“

“Oh yeah, I know that one!” Derrick said.

I thought William might mention this song, so I showed students a photo of Stevie Wonder I printed from the Internet and said, “This song was written by a musician and singer named Stevie Wonder.”

“I know him!” said Parris.

Then I showed children a photo of Patty and Mildred Hill that I also found online.

“Some of us also might know ‘Happy Birthday to You’,” I said. “That’s the birthday song we’ve been singing in school. These two people are sisters named Patty and Mildred Hill. They wrote the ‘Happy Birthday to You’ song a long time ago.”

I hoped showing children a photo of Patty and Mildred Hill would convey that “Happy Birthday to You” wasn’t a universal, authorless birthday song, but rather a song that two people wrote, like any other song. In our constant use of “Happy Birthday to You,” we embed dominant white, Eurocentric culture in our classrooms without acknowledging that we are doing so. In singing only this song, we imply that white culture is relevant for everyone, even though it isn’t. Showing the Hill sisters’ photo and saying their names was one way to call attention to white culture as a culture, rather than everyone’s culture.

After I showed the Hill sisters’ photo, children continued sharing birthday songs they knew from home.

“I know a song in Spanish called ‘Cumpleaños Feliz!'” said Beln, looking at me through her glasses.

“There’s a birthday song in French!” said Gwen, nodding, her eyes wide.

“I know this one!” Marco started giggling. “You look like a monkey and you smell like one too!”

Leo sat up tall in his basketball jersey and asked, “I wonder how you sing ‘Happy birthday’ in Wolof?” Fatima, whose family speaks English, French, and Wolof, a language from Senegal, said she could ask her parents and report back.

Many children wanted to ask their parents about other birthday songs they knew, so I suggested that we request this information by writing one big letter to their families. Students suggested words for this note and helped write some words; I wrote the rest.

While the class was at recess, I took a photo of the letter and put copies of the photo in folders that children take between home and school each day. In addition, I gave each family two pieces of paper on which a family member could write lyrics for a birthday song (or songs) they knew; their child could illustrate. I also sent an email to families clarifying the goals of the study.

Over the next two weeks, families sent in 22 different songs in eight different languages: Arabic, Hebrew, Spanish, French, Italian, Mandarin, Japanese, and English. We received six different birthday songs in Spanish — songs unique to the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Colombia. Vesna shared the lyrics for a birthday song in Serbian, her first language. We received different songs in English as well, including “Babies Are Born in the Circle of the Sun.”

I put each family’s sheets of song lyrics into a book that children could read during our “community reading time,” which happens after they clean up from choice time and snack. I often saw students read the birthday songs book with a partner, singing classmates’ songs to themselves the best they could, even if they didn’t speak that language.

Sharing Songs and Talking About Difference

A week after families began sending songs, I sat with children at morning meeting and held the book with students’ birthday song lyrics. I turned to “Sana Helwa Ya Gameel,” a birthday song in Arabic. Amal, whose mother speaks Arabic, English, and French, had brought in the lyrics.

I asked Amal if we could share her song. She hugged herself, smiled, and quietly said, “It’s in my language.” “Is that OK?” I asked. She nodded, but said she didn’t want to sing it herself. So I played a version of the song I found on YouTube. As the song played, Amal grinned. Her smile grew bigger as classmates clapped along to the beat. When the song was done, students described it as “fast” and “happy.”

The students seemed to have a range of feelings about sharing their songs. Like Amal, sometimes they seemed reticent at first but happy when they saw classmates enjoying the music. Some children were eager to share their song, but didn’t remember the words. Others, like Belén, boldly sang their song for the class. No one said they didn’t want to share, but if they had said no, that would have of course been fine too. I wanted the children to feel comfortable.

For two weeks at every morning meeting, I played two or three songs each day. Students listened with interest and described songs as “jazzy” or “high” or said you could “clap your hands” to them. I wondered if my students might express discomfort with songs that were different from their own and those feelings surfaced one day when Tian shared his birthday song in Mandarin, “Zhù Ni Shēng Rì Kuài Lè.” I played a recording of his mom singing the song (after school one day, she had sung it into the voice recorder on my phone).

When the song was done, Miguel said, “That’s funny.”

Tian frowned.

“Tian, how you are you feeling?” I asked.

“It’s not funny,” he said.

When I talk with children about differences in aspects of their identities — language, race, gender, and more — sometimes I feel nervous. I don’t want to say something wrong or accidentally hurt a child’s feelings. But I know that we need to have conversations about these topics so children can practice talking about difference with empathy and respect. If conversations are empathetic and respectful, I hope children will feel safe sharing their home lives at school and feel like a valued member of the community.

I tried to lead a conversation that would protect Tian’s feelings and create some general guidelines for talking about the songs.

“Sometimes when we hear a song that sounds different from what we sing, we might think it sounds funny,” I said. “But that word can make people feel upset. What are ways we can talk about these songs and help people feel good?”

At first, the students focused on what not to say. “You can think it sounds funny, but you shouldn’t say it,” Leah said.

“What can we say instead?” I asked.

“You can say, ‘That’s different from what I sing,'” Luca responded.

Derrick added, “You can say it sounds funny if it’s OK with the other person, and if it’s not OK then you can’t say that.”

Tian’s expression softened.

I suggested that we listen to Tian’s song again. As the song played, no one giggled; the children leaned forward, quiet, listening even more closely.

“What If We Wrote Our Own Birthday Song?”

After about two weeks, we had listened to everyone’s birthday songs from home and had also looked at a world map and talked about places we recognized. Many of the children noted places like Puerto Rico, Curaao, Mexico, and France, where people in their families were born. We read books about birthdays, such as Before You Were Here, Mi Amor by Samantha Vamos and Happy Birth Day! by Robie Harris, and the students started playing “birthday” in the pretend area. I felt like it was time to use what we had learned about languages and birthday traditions.

A few days later, I presented an idea to the class that I got from a friend: “What if we wrote our own birthday song?” I thought creating a song could allow the students to reflect on and use what we had learned and when I suggested it, some of the children sat up, looked at me with excitement, and agreed.

“Maybe we can put it in different languages,'” said Luca.

The following day, I showed a poster featuring the nine different ways we had learned to say “happy birthday” so far. I suggested that we sing these phrases to the tune of the Stevie Wonder birthday song or the tune of Amal’s birthday song in Arabic. These were the songs they seemed to enjoy the most and we took a vote. In the end more children voted for the Arabic song tune, but to take care of some children’s disappointment, we agreed to sing “happy birthday” in the Stevie Wonder way at the end of the song.

In late May, we made our class birthday song into a songbook. I put each phrase of the song on paper and each child illustrated a page during writing time. I put this book on our bookshelf and each child took a copy home.

Singing Raucously

The whole point of studying birthday songs was to help children feel welcome to use home languages at school and learn about languages that classmates speak. A few weeks after we made the songbook, the curriculum appeared to be working.

During a morning meeting in June, I asked the children to shake hands around the circle. I was assuming they would greet one another in English; it had been the default language for our greetings. But then Fatima said “Ni hao” to Belén. Belén said “Hola,” to Tian. Tian said “Bonjour,” to Marco. They kept going around the circle, saying hello not only in languages they knew from home, but also in languages they learned from their classmates over the last several weeks.

I noticed other subtle changes too. Luca, who is bilingual in English and Italian, used to write stories only in English. But one day in June, he showed me his story and said, “It’s in Italian.” Miguel, who speaks English and Spanish, labeled some of his drawings in Spanish. I heard Belén and Gloria talking in Spanish as they played a math game, whereas before, I only heard them play in English. I can’t say for sure that our study of home languages and birthday songs prompted these shifts, but they may have played a small role.

Moving forward I may need to adapt the curriculum depending on students’ cultural or religious backgrounds. For example, students who are Jehovah’s Witnesses may not celebrate birthdays, in keeping with their family’s faith. In this case, to learn more about each other and our families, perhaps we would focus on family songs or artifacts instead so everyone would feel included. I also would note that some families don’t celebrate birthdays and spend time together in other ways that we can learn about.

I also will need to make sure that we explore the meaning and history of birthday songs more deeply. For instance, while I informed students that Stevie Wonder had written “Happy Birthday,” I didn’t share that he wrote the song in honor of Martin Luther King Jr., and that the song is part of a long struggle to make King’s birthday a holiday. Singing the song bonds us to that struggle and reminds us of Dr. King’s legacy. The next time we study birthday songs, I plan to share the song’s full history, along with the history of other birthday songs. Perhaps I could invite all families to write as much or as little as they like about why their song is meaningful for them and share that information with students.

Toward the end of the year we still had a few birthdays left and each one was a chance to put what we learned into practice. As with each birthday, when it was time to sing, I asked the birthday child which song they wanted. One student chose “Cumpleaños Feliz” and we sang it joyfully. Another day, for a different birthday celebration, the birthday child asked for our class birthday song and we sang it raucously. For the first time, I felt like we were actually celebrating children’s birthdays.

Resources

Flor Ada, Alma. 2002. I love Saturdays y domingos. Simon & Schuster.

Harris, Aisha. 2016. “Stevie Wonder Wrote the Black ‘Happy Birthday’ Song.” Slate. http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/wonder_week/2016/12/stevie_wonder_wrote_the_black_happy_birthday_song.html

Harris, Robie. 1996. Happy Birth Day! Candlewick Press.

Haugen, Brenda. 2004. Birthdays. Picture Window Books.

Vamos, Samantha. 2009. Before You Were Here, Mi Amor. Viking.

***

The Birthday Song

by Children in Kerry and Vesna’s Class

(This first part is sung to the tune of “Sana Helwa Ya Gameel,” an Arabic birthday song.)

Happy birthday to you!

¡Cumpleaños feliz!

Joyeux anniversaire!

Tanti auguri a te!

Hayom yom huledet!

Danas nam je divan dan!

Otanjubi omedetou!

Sana helwa ya gameel!

Zhù ni shēng rì kuài lè!

Happy birthday!

Happy birthday!

Happy birthday to you!

(The next part is the chorus for “Happy Birthday” by Stevie Wonder)

Happy birthday to you!

Happy birthday to you!

Happy birthdaaaaaay!

Happy birthday to you!

Happy birthday to you!

Happy birthdaaaaaay!

Happy birthday to you!

Happy birthday to you!

Happy birthdaaaaaay!