How Rank-and-File Organizing Pushed United Teachers Los Angeles to Take a Stand on Palestine

A couple of weeks after Oct. 7, 2023, I got a call from a union brother and friend. He wanted to know what I thought about bringing a ceasefire motion to one of UTLA’s regional area meetings. Michael had always been more involved in the union than myself, but we were like-minded, and he knew I had been active in the movement to stop the Iraq War. He also knew I was Jewish and was curious how I felt about Israel.

That day I remember sitting in my car long after my 20-minute drive home from my elementary school. Did I think it was a good idea? Michael wanted to know. Would it be divisive? Would it be performative? After all, what impact could our local union have on U.S. foreign policy?

These were important questions, and though I didn’t give them the consideration they deserved that day, before long they would lead me on a journey of both learning and activism. Soon, Palestine would move from the margins to the center — of both my life, and my union’s progressive politics.

Where We Began

At that time, I am sad to admit, I had been avoiding the Israel/Palestine issue for years. My Jewish identity was something that had felt ambiguous for most of my early life. Having grown up the child of a non-Jewish father and a secular Jewish mother in a community where I knew no other Jews, I mostly kept my identity hidden. Much of what I knew about Jewish culture came from my extended family. My grandmother had been to Israel many times, bringing back tchotchkes for my older sister and me, including necklaces with hamsa charms that we treasured. We celebrated Jewish holidays at her house every year, and loved reciting the blessing over the menorah, eating matzo ball soup, and hunting for the afikomen.

When my older sister turned 18, Birthright, the organization that offers free trips to Israel, didn’t yet exist. Still, to my nana, visiting Israel was so important that she paid for her to go. After her three-week tour concluded, she came back with a deep tan and a stronger connection to her Jewishness. When it was my turn, however, the choice did not hold any attraction. I knew there was violence there, I did not look forward to the desert climate, and exploring my roots was not a priority at the time. Israel remained a vaguely exotic place in my mind, thought of during Passover seder, if at all.

By the time my son was born, my feelings about being Jewish had evolved. Now I lived in a community with other Jews, and I wanted to instill in him a positive orientation to his identity. My husband had found that one of the top preschools in the city was at the Jewish Community Center. Enrolling him there was a no-brainer. For the first five years of his life, Noah celebrated and learned about every major Jewish holiday, collected tzedakah for children in Israel and sang “I’m a Little Latke” at the Hanukkah performance. Those early years at the JCC were precious, and, through our son, we developed friendships with several Jewish families.

Even so, I thought very little about Israel and even less about Palestinians living under occupation. The Israeli flags all over the JCC didn’t faze me, and at the same time I found it ridiculous when friends and family members “checked in” with me after Oct. 7. What was happening in the Middle East was something I had “checked out” of my whole life.

So when Michael approached me that afternoon, I discouraged him. I thought our union had more pressing issues to take on, and we couldn’t afford to divide people over something that didn’t directly affect us. He heard me out but was clearly unsettled. He said he would think it over. I had a lot to think over myself.

I was inspired at the time by young employees of major corporations like Amazon, Starbucks, and Trader Joe’s that had started to organize. Our own local, United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) had become increasingly progressive over the past 10 years, and we had gained some significant wins. One important strategy to build our power had been to join with student and community groups and include “common good” demands into our bargaining. We had also started expanding our bargaining team, which included dozens of teachers and Health and Human Services workers. We created systems of organization to ensure that rank-and-file members stayed engaged with our contract demands through escalating actions, culminating in a massive strike in 2019. It appeared to me that labor was enjoying a sort of renaissance in the United States, and I started to believe that maybe we could leverage that power politically.

At the same time, Israel’s merciless bombing campaign was destroying hospitals, schools, and thousands of lives. I kept hearing about hidden Hamas tunnels, and Hamas using innocent civilians as human shields as the reason for the nonsensical brutality, but news outlets like Democracy Now! helped me see that there was another side to the story. As the body count piled up, so did my cognitive dissonance. My conscience wouldn’t allow me to ignore this issue anymore: It was time for me to study all I could. The learning would take time — lots of incremental steps, flip-flopping, conversations with friends and family — but the moral stance underneath it all would never change. I had always been, and always would be, against war and oppression. So, before I knew who Theodor Herzl was, or could find the Gaza Strip on a map, I reached back out to Michael to tell him I had changed my mind.

He’d already begun drafting a motion with the help of a few comrades and welcomed my edits. We had a reason to be careful with language. In 2021, after an outbreak of violence in East Jerusalem as Israeli police and settlers attempted to forcibly displace Palestinians from the neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah, Michael had been part of a group of rank-and-file members who had brought a motion calling on UTLA to “endorse the international campaign for boycotts, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) against apartheid in Israel.” The motion passed easily in several of UTLA’s eight areas, but it needed to go through the Board of Directors before it came to the House of Representatives (HOR), the policymaking body of the union. Before it could get there, an intense backlash from pro-Israel Jews in the union, in partnership with outside groups, pressured the Board of Directors to kill the motion. It had gotten so bad that threats were made on the life of our union president Cecily Myart-Cruz, who had to hire security to stand watch outside her home. Several union leaders involved in the controversy had learned the hard way how pro-Israel groups like the Jewish Federation and Anti-Defamation League would mobilize to divide and silence us.

So when word got out about this new motion, many leaders reached out to us, trying to convince us to drop it. We understood they were concerned for our union president and what this would do to our union based on past events. In addition to risking the ire of Zionists both inside and outside the union, we were amid a consequential school board election and could not afford to be divided, they argued. However, we weighed the risks against what we felt was a measured ask and decided to proceed with a ceasefire motion.

The motion passed resoundingly in three out of four areas, and those of us in the House of Representatives looked forward to voting on it when the time came. A couple of weeks later, we learned that the motion would not be coming to the HOR. The Board of Directors had again quashed it.

By bringing a motion every month, we had an opportunity to keep the genocide at the forefront of people’s minds, sharpen our arguments and organizing, and win over union leaders to stand against Israeli oppression.

Connecting Organizers Across Los Angeles

While we regrouped to figure out how we would handle this setback, there was organizing going on in other places around the city. LA Educators for a Ceasefire (LAE4C) had been born in the North area of UTLA, where a couple of young leaders had brought their own ceasefire motion to their area meeting. The motion did not get a majority, which prompted another spirited activist, Hannah, a Jewish elementary school teacher who had voted for it, to pass around a sign-up sheet for any members interested in organizing around Palestine. “I was impressed by her boldness,” remembers David, a middle school teacher who signed up and later became a member of LAE4C’s steering committee.

Meanwhile, activists in UTLA’s Central area were initiating organizing of their own. Alia, a Muslim high school teacher, remembers being dismayed to see an Israeli flag posted on the LAUSD website after Oct. 7. Her outrage prompted her to wear her keffiyeh to work the next day. She was approached by Mika, a Jewish educator, who remembered, “I was so excited to see someone in a keffiyeh. It made me feel less alone.” Meanwhile, Iris was waiting for her union leadership to respond to what was happening in Palestine. “I thought for sure UTLA would put out a statement or something.” After several days with no response, she started looking to organize with other union members. David and Iris, both Latine educators, along with Alia, Hannah, and Will, a Jewish middle school teacher who had previously organized with Hannah, would eventually form the bulk of the first steering committee of LAE4C.

The North activists met the Central activists, all marching in their red UTLA shirts, at the Children’s March organized by the Palestinian Youth Movement in December of 2023. The google form invitation made its way through the various formal and informal networks of our union, and before long the LAE4C WhatsApp chat surpassed 300 members. Though the majority were not very active, there was a core of young, motivated individuals who spent hours in meetings strategizing, writing motions, organizing and attending protests, and continually reaching out to engage others. Their dedication eventually turned LAE4C into a force to be reckoned with.

At our HOR meetings, which met over Zoom, many of us displayed backgrounds with our watermelon logo and name in an effort to show our strength and unity. There were always a handful of Zionists who spoke against every pro-Palestine motion we brought, citing the same reasons: This conflict didn’t affect us, it was divisive, we were being performative. They also accused us of antisemitism, spread lies that none of us was Jewish, and threatened that thousands of members would leave the union if we passed any motions supporting Palestine. These attacks became repetitive, as every month we attempted to pass a motion, though we rarely succeeded.

Our repeated failures motivated us to become more organized: We regularly met before each meeting to strategize talking points documents that were shared with all HOR members. Many of us were already involved in grassroots work in our communities, or in other union committees, and we leveraged those relationships to keep building our presence and increase our support. We arranged speakers ahead of time and reminded people to attend. During the meeting, we used group chats to strategize, which helped us counter both con arguments and parliamentary roadblocks. When HOR elections were announced, we recruited seven LA Educators for Justice in Palestine (EJP) activists to run for the HOR, increasing our numbers when many of them were elected.

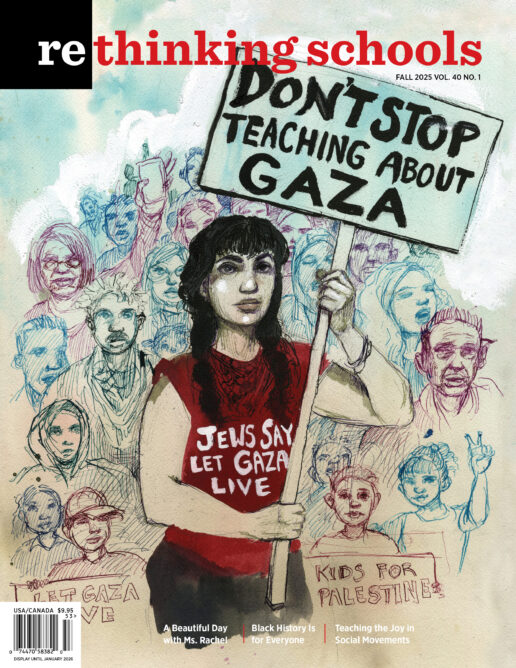

In January 2024, we had our first success by passing an Academic Freedom motion. This motion came from Educator Defense Network, another grassroots group that brought together leaders across the city. Their mission was to protect teachers who were being targeted by Zionists for teaching the truth about Palestine or LGBTQ+ rights. One of these teacher organizers was bullied about their transgender identity, harassed, and ultimately strong-armed out of their school. Others, who accurately identified Israel as a colonial project, were doxxed and attacked online. Having a Palestinian flag hanging alongside other flags in your classroom, wearing a button of support for Palestine, or wearing a keffiyeh made you a target. In addition to their harassment campaigns, pro-Israel organizations also worked with legislators to censor ethnic studies, leaving out Palestinian and Arab voices. Some even partnered with the Freedom Foundation, who funded billboards that encouraged people to leave UTLA due to its supposed antisemitism, an accusation that had gained traction back in 2021 because of the BDS motion.

Nevertheless, in March 2024, we finally passed a true ceasefire motion in the HOR. It appeared that our efforts were paying off: By bringing a motion every month, we had an opportunity to keep the genocide at the forefront of people’s minds, sharpen our arguments and organizing, and win over union leaders to stand against Israeli oppression.

From Ceasefire to Divestment

As we were busy passing our motions, college students across the country were getting ready for a riskier protest. In April of 2024, UCLA’s first encampment started. Inspired by the bravery of these students, Alia, who had been a member of Students for Justice in Palestine while in college, proposed our group change its name to LA Educators for Justice in Palestine. That month in the HOR, EJP brought and helped pass a motion calling on L.A. Mayor Karen Bass to stop the repression at the encampments and support student protestors. Unfortunately, UTLA’s call didn’t have much effect; neither the mayor nor UCLA did anything to protect the students, who were attacked by both counterprotesters and police. However, EJP members organized visits to those encampments where we brought food, helped build barriers to protect students from the violence they were facing, and linked arms with them as they faced their tormentors. The severity of the backlash against these peaceful protests, while frightening and destructive, became a major factor in convincing others of the righteousness of speaking out against the genocide.

In January 2025, Maya, who organized with Ed Defense, reached out to include me in a group of Jewish, Latine, Asian, White, and Palestinian educators who were interested in countering the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, which conflates criticism of Israel with antisemitism. It seemed to us that a key problem we confronted in many of our organizing conversations was that a false definition of antisemitism was widely held, one that gave cover for Israel to do anything it wanted. Although the IHRA working definition may seem uncontroversial at first glance, seven out of the 11 examples of antisemitism it provides are related to criticism of Israel. The IHRA working definition was adopted in 2019 by the Trump administration. Challenging this definition seemed important.

Maya sent me a link to the PARCEO curriculum, which was the first resource I had seen that framed antisemitism as separate from criticism of Israel. She asked if I wanted to help the group bring this curriculum to UTLA members. We quickly planned a workshop titled “Combating Antisemitism Through a Lens of Collective Liberation” in coordination with Jewish Voice for Peace-LA and PARCEO. Excited about our event, the group asked UTLA to sponsor our workshop with a $499 donation at our February HOR.

That month marked the first in-person HOR meeting since 2020. Although Zoom had made it easier to include voices from across the district, meetings were becoming contentious. Our Zoom backgrounds told the story of our alliances: Some of us showed up with EJP backgrounds, some had Israeli flag/American flag backgrounds, some had “We are UTLA” backgrounds. Feelings ran high, and discourse was not always polite. It appeared that the union leadership thought meeting in person might help mitigate some of the division that was brewing. I looked forward to meeting more than 150 fellow HOR delegates, most of whom I knew only by their two-dimensional selves.

At this meeting, members of Ed Defense introduced our motion, which passed easily, due to a sizable EJP constituency that had been established, though not without the usual bluster from pro-Israel members, one of whom falsely claimed that none of us lined up to speak in favor of the motion was Jewish.

Our Ed Defense workshop in March was a lovely, community-building event with allies and interested persons from both within and outside the union. By building a common understanding between Jews and non-Jews that the fight against antisemitism belongs alongside the fight against any type of oppression, we hoped to build capacity to shift the discourse toward liberation for all. What we knew for sure is that we were building our trust and capacity for future organizing with each other.

At next month’s HOR, pro-Israel members brought a new motion asking UTLA to endorse another antisemitism workshop, this one put on by the Association of Jewish Educators, the Jewish Federation of LA, and “their partners.” We questioned these undefined partners, which we assumed to be the ADL among others, and pointed out the ways in which the Jewish Federation had worked to undermine our union democracy. This motion was defeated by almost a two-to-one margin. The EJP contingent had other wins at this meeting, asking our union to denounce the attacks on college students, and to send a letter to University of California regents, California State University Board of Trustees, and the California Community Colleges Board imploring them to support students’ free speech. We also asked the union to call on LAUSD to not adopt or teach ADL-sponsored curriculum. It was clear that the organizing of the last year and a half had meant something. We had developed a sizable constituency in the House and had begun to help shift opinion in that space.

This was the signal that many of us needed. In EJP, a subcommittee had formed earlier in the year to work with CalSTRS Divest, a coalition of grassroots, teacher-led organizations calling on our pension fund to “Immediately divest from all companies and bonds that enable, facilitate, and profit from weapons manufacturing and human rights violations, in particular, violations of international law, military occupation, apartheid, and genocide.” But when I was approached by Alia back in January, requesting I bring a divestment motion to the HOR, I had declined — despite understanding that it was possibly the most effective strategy to help end the genocide. Several of us in EJP were concerned that without properly laying the groundwork, we could set our work back. It was, after all, a BDS motion that began the initial harassment campaign back in 2021. But the educational work we had done to separate criticizing Israel from being antisemitic and the success of our motions at the first in-person HOR meeting convinced us we could now move forward.

A five-area coalition brought the divestment motion to our area meetings. It sailed through the Board of Directors, and passed easily at April’s HOR, at which none of UTLA’s pro-Israel members seemed to be present. It soon became clear that they had given up on this space, but we knew they were busy in other areas working with lawmakers to promote Zionist changes to the ethnic studies curriculum.

Even when we are exhausted, we continue to do the work. Because showing up for Palestine is also showing up for each other.

Now, when our country has aided and abetted a genocide for two years, and Palestinians continue to be decimated not only through bombs, but by starvation, we feel a mixture of despair, fury, and grief. We reflect on the impact of our work and wonder what more we can do. We continue organizing to hold our lawmakers and our pension fund accountable. We participate in protests. We teach every day, helping our students to think critically about Palestine and the world around them.

Even when we are exhausted, we continue to do the work. Because showing up for Palestine is also showing up for each other. As Alia said, “Standing up for the Palestinian people isn’t divisive. Look at how so many of us have been brought together to do this work. The union is stronger now because of our energy.” As for myself, although I still get nervous, I no longer think twice about speaking out against Israel. I have learned that none of us is free until Palestine is free. It was my union siblings who taught me that.