How One 2nd-Grader’s Story Inspired Climate Justice Curriculum

“I don’t know what to write.”

We were several days into our writing unit on personal narratives and Natalie was staring at a blank piece of paper. I went through the questions I ask students to try to help them generate ideas. Pets? Family celebrations? Learning to do something new? Memorable trips you have taken?

“I visit my grandparents in Idaho every summer.”

That was the spark.

Natalie wrote about being Nez Percé and Lakota, her dress and shawl that her grandmother sewed for her, and the dances that bring her joy.

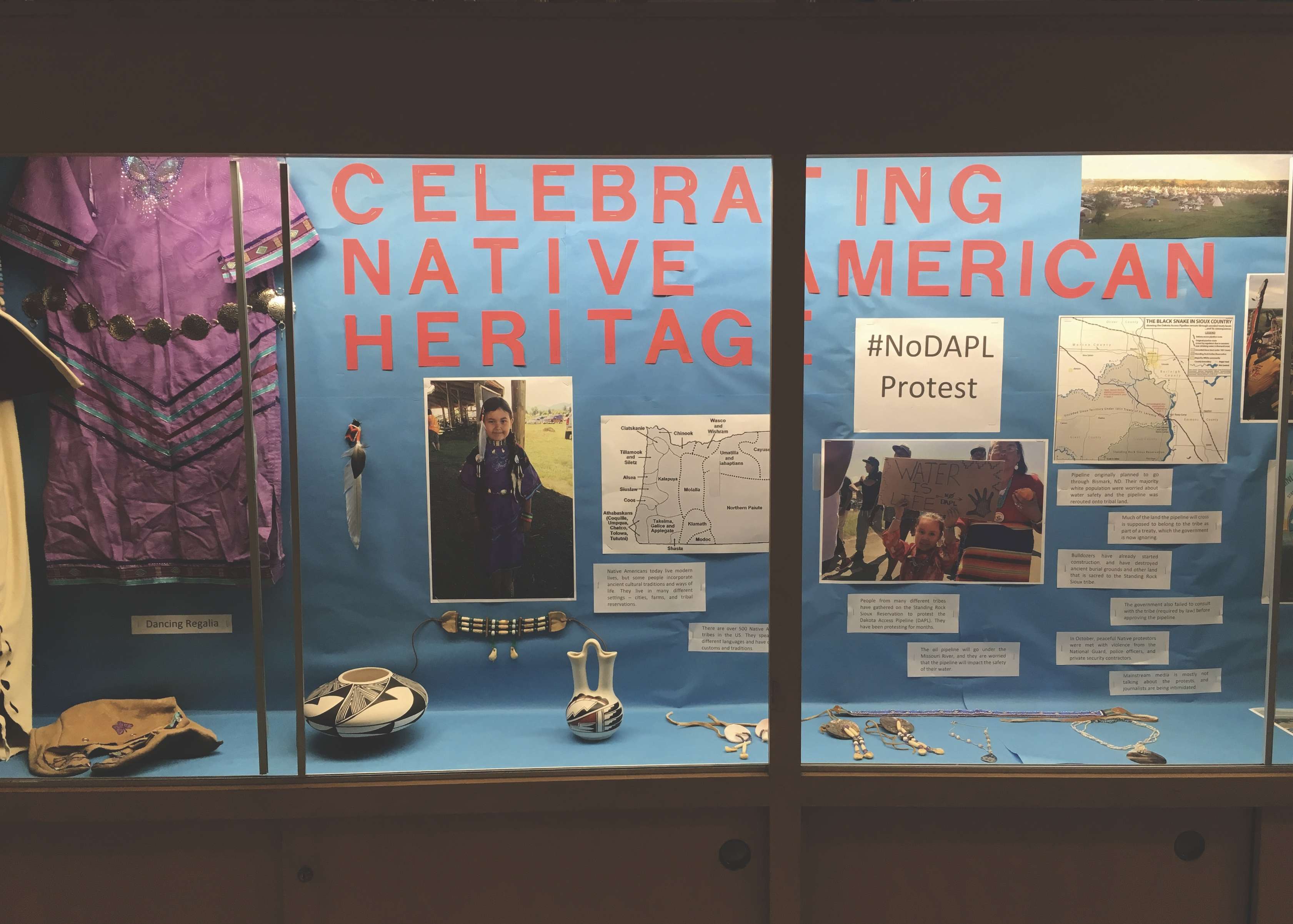

I shared her story with her parents at conferences and they were moved. Our school has a parent equity committee and throughout the year they create displays in the hallway cases. The week after conferences, I was pleasantly surprised that Natalie’s parents had made a display case in the hall of the school to celebrate Native American Heritage. Included in it was a photograph of Natalie in the dress from her story, jewelry and pots, and a map of Indigenous land. The display also included information about the Dakota Access Pipeline protest at Standing Rock.

One day our class stopped at the display and I read everything to them. That’s when the questions began and our climate justice study began in earnest.

“Why are they putting the pipeline there?” “How many pipelines are there?” “How many spills are there?”

I started by looking up a map of existing pipelines in the United States. I printed it out and hung it on the board. The crisscross of lines was so dense in the Southern states we couldn’t make out individual lines. Students gasped.

Then I looked up oil spills in the United States and found Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration data on the Department of Transportation website. I printed out their list of Pipeline Failure Investigation Reports and it was more than six pages in a tiny font of pipeline failures spanning from 2003 to 2013. As I flipped page after page of spills, their shock grew.

“That is so many!” “I thought it was just a couple pages but it just keeps on going!” “Why do we put in more pipelines if there are so many spills?” “What happens to the water and animals that live there?”

I could see that my students were hungry to learn more but I am no expert. There is very little curriculum on climate change and I had to be willing to learn alongside my students. I wanted my students to start to understand the scope of change needed to deal with climate change as well as their own ability to push for that change. Fortunately, I had colleagues who felt just as passionately that our students deserve to explore their questions and concerns about our planet. We met frequently to plan and share resources in order to bring this learning to life in our classrooms.

Fossil Fuels

I started with fossil fuels.

I read Molly Bang’s Buried Sunlight to the students, which explains how fossil fuels are formed and the many ways we use them. I read aloud books introducing the idea of the commons and our shared earth and resources, and I read aloud about greenhouse gases, global warming, and climate change. I created a wall chart by first drawing simple illustrations of the formation of fossil fuels and the greenhouse effect and transcribed student responses to questions I asked that included “How are fossil fuels formed? What are they made of? What are greenhouse gases? What makes carbon dioxide? Methane? Nitrous oxide?”

Next, I wanted students to explore the difference between individual actions versus ending our dependence on fossil fuels. I wanted them to understand our country’s reliance on fossil fuels and that we would need to make big systemic changes in how we get our energy in order to break free from that dependence. Together we made a list of all the ways we use fossil fuels for energy. Students saw that we rely on oil and gas for most of our electricity and vehicle transportation needs.

“If we all shut off the lights when we leave a room or ride our bikes more, is that going to solve our problems with pipeline spills or drilling for more oil? Is that enough to end our dependence on gas and oil?” I asked.

“No!” they responded. “We still have all the cars!” “And we heat our houses with fossil fuels.” “And our refrigerators and TVs.”

I then posed other questions to them: “Could we stop using all fossil fuels tomorrow and still turn on our lights and heat our house? Do we have other ways to create electricity?”

In order to answer those questions, I knew students needed to learn about renewable, green energy sources — water, wind, solar. I checked out as many books about renewable energy from the library as I could find at various reading levels. I read some aloud to the students. I made charts for wind, solar, and water starting with simple drawings of how wind turbines, solar panels, and water turbines work that students could reference and replicate. Students shared what they learned from the read-alouds and helped to define key terms while I transcribed.

I then gave students papers with headings such as “What I Know About Fossil Fuels” and “What I Know About Solar Power” and asked them to show me everything they learned about the topics. Students worked individually, with partners, and in groups to read and write what they were learning about fossil fuels, global warming, climate change, and green energy. I wanted to see what they understood from the read-alouds, discussions, and books. This allowed students of all reading and writing levels to show their learning in words and pictures. They wrote and drew pictures of how solar panels and wind turbines worked. They learned about hydroelectric power. One student took it upon himself to organize the list of oil spills, state by state, to see where the problem was the worst.

Storyline and the Carson Environmental Oil Company

At this point in the year, each 2nd-grade class was deep into our neighborhood Storyline unit. Storyline is a method of teaching that starts with creating a place and characters that inhabit that space. As the story develops, incidents occur that are developed by the teachers, and the students, in character, must figure out how to respond. We were exploring neighborhoods by creating our own neighborhood with characters that live and work there. Some of our guiding questions were: What is community? What makes a family? What makes a home? Who gets to live where? What happens if you cannot afford a home? What would make a welcoming and inclusive neighborhood? What jobs might we have in our neighborhood? How do communities solve problems?

By now, everyone had a character with a home and a job, including me. As a class, students decided that businesses and services like a library, a public school, and a homeless shelter were important to creating a welcoming community. We built a wall map of our neighborhood. The school display case had inspired similar conversations in the other two 2nd-grade classes and my colleagues and I shared resources in all three classes to start to explore the answers to students’ questions. As we started to ask questions about solving community problems and ways to make changes through elected office or civic engagement, my colleague, Christina Self, had a stroke of genius.

She wrote a letter from Mr. James Spencer, CEO of the Carson Environmental Oil Co., asking our three communities if we wanted an oil pipeline running through our towns.

Dear Mayors of Twilight City, Ocean Valley, and Happy Town,

I am the CEO of Carson Environmental Oil Company. We are interested in building an oil rig off the coast of Twilight City and Ocean Valley. We would drill the ocean floor for much-needed oil to send out to surrounding communities. We would have to run an oil pipeline through Twilight City, Ocean Valley, and Happy Town in order to send our oil across the state. The pipelines would first go through land without buildings on it, such as forests and parks, and may have to cross the river in Happy Town.

There are many benefits to us coming to your town to do this work. First, this will bring many new high-paying jobs to your area. Also, the town will receive a portion of the profits that can go to the improvement of the town. Of course, there will be a few negatives, but not many. We will have to cut down some of the trees in the forest or park and then drill below the river to place the pipe. We may need to buy some homes to tear down in order to lay down the pipeline. I know this might be difficult for some families, but we will pay homeowners so they can relocate. We think the benefits will far outweigh the negatives. Carson Environmental Oil is committed to safety and taking care of the environment. We will do our very best to keep all of the towns safe and to make sure the transport of the oil is safe and that there are no accidents that will harm the natural environment.

We would like to begin working immediately, so please find a way to communicate and get feedback from the citizens of your towns. We look forward to a prompt response.

Sincerely,

Mr. James Spencer

Our school secretary came in with the letter saying it was very important and I had to sign for it. With great surprise — “What could this possibly be?” — I opened the letter and read it to the class. I couldn’t get through the letter before students started expressing their outrage. They couldn’t believe that an oil company would even suggest putting a pipeline through our community. Suddenly it was all anyone could talk about in 2nd grade. The neighborhood communities they created were real to students and they felt invested in this place that lived somewhere between their imagination and the real world. The students talked about it on the playground. There were mayoral races in the neighborhoods and the pipeline became a key issue in the race. During the candidate speeches some students spontaneously created protest signs opposing the construction of the pipeline.

After the students elected a mayor, I advised them to call a town hall meeting so members of the community could give testimony about the pipeline.

“There could be an oil spill and it could go into our water!” “We won’t be able to drink the water. We won’t be able to catch fish and eat them.” “They would have to chop down trees and what about the animals that live in the trees? It would harm wildlife.” “Without trees, we can’t breathe.”

For more on teaching climate justice, check out A People’s Curriculum for the Earth edited by Bill Bigelow and Tim Swinehart.

Remember Standing Rock

I then had students write persuasive letters to the mayor stating whether or not they supported the pipeline. We went through Mr. Spencer’s letter and made a list of pros and cons. I used our persuasive letter writing unit to teach them how to write a strong argument with supporting details.

The mayors from all three communities met to read over the letters they received and talk about what to do. They held a vote in each neighborhood and students unanimously rejected the pipeline. But then I asked students to remember Standing Rock. They learned that another community had initially rejected the pipeline so it was rerouted, impacting a new community. I wanted students to explore the idea that to shift a problem away from us doesn’t get rid of the problem, it simply makes a problem for someone else.

“Is it fair that this pipeline will now become someone else’s fight?” I asked.

“No!” they responded. “No more pipelines should be built!”

“If communities still use fossil fuels for most of their energy, pipelines will be built to send oil and gas all over the country. What do we need to do to change that?” I asked.

“Solar panels!” “Green energy!” “Electric cars!”

I wanted them to reflect on their own agency and power to act right now. I wanted them to hear about youth inspiring climate action in communities all over the country so they felt empowered rather than defeated. We watched videos and read about Tokota Iron Eyes, who, with other Sioux youth created an online media campaign and petition to bring attention to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Many credit these youth with sparking the #NODAPL movement. The activists talked of respect and care for the environment, protecting the water and the land to sustain life for all living creatures, and leaving future generations a healthy planet. I read students the words of Tokota Iron Eyes: “This entire movement was started by the youth. It just started so small. And then, this entire camp was built.”

We watched videos about the youth from Our Children’s Trust, suing the United States government over the government’s actions that cause climate change and fail to protect public resources. They learned about proposals in our own state to build a liquefied natural gas terminal through a video created by students at the Sunnyside Environmental School, a public school in Portland. This video helped students understand fracking and the amount of resources that go into extracting liquefied natural gas. It was aptly named “LNG: Just Another Dirty Fossil Fuel.” At the end of the video, the youth filmmakers asked viewers to call or write our governor to ask her to put a halt to the proposed liquefied natural gas terminal.

I invited students to write to Oregon Gov. Kate Brown if they wanted to share their opinions about the proposed liquefied natural gas terminal. Students who chose to write were able to speak knowledgeably about fossil fuels, climate change, and global warming as well as their right to a livable planet. Many demanded not only a rejection of the liquefied natural gas terminal, but also of any further fossil fuel infrastructure. Instead, they called for investments in renewable, green energy. Their responses included:

“If you put the liquefied natural gas pipeline, that means cutting down animal homes. Instead we could make solar farms, wind farms, solar panels, and underwater turbines. California and Washington said no, that means we can say no! I do not want a dirty world. I want a clean future!”

“I don’t want to have those darn fossil fuels because it will go into the air and affect people that have asthma. If it continues it could kill them! We can say no even if we are 7. Also little kids have the right to say no. I want no fossil fuels.”

“I want a future with opportunities. I want a future with exploring the forest trees not a forest without trees.”

“I don’t think we should have liquefied natural gas in Oregon. If we put the LNG terminal in Oregon, we will still be relying on fossil fuels. I think we should start relying on wind and solar power. Wind and solar power is renewable, unlike LNG. Also LNG is bad for the environment in many ways.”

“We would speed up global warming and the greenhouse effect. Why can’t we use renewable energy like solar power? The future I want to live with is no fossil fuels and I want to live with renewable energy.”

“I know I’m a child. I’m saying we can stop global warming. We can say no.”

“We deserve a better future.”

I learned two valuable things throughout our study of climate justice that have continued to shape my teaching. I learned how to take a student’s interest or inspiration and follow the crooked path to make meaning together. I didn’t have all the answers: Often I was learning as I researched and explored how to teach climate justice to students hungry to learn about it. Secondly, I learned just how capable young people are of grappling with what seem like complicated ideas. It was clear to them that our current dependence on fossil fuels is not only unsustainable, it is unjust. Educators have a responsibility to start teaching about climate justice at an early age and to teach our youth that they have an important voice that deserves to be heard. It isn’t just about their future. They live here now. This is their world too, and the impacts of climate change are already being felt. In order to combat despair, students need the tools to think critically and creatively about how to respond to the most important issue of our lifetime.

RESOURCES

Bang, Molly and Penny Chisholm. 2014. Buried Sunlight: How Fossil Fuels Have Changed the Earth. The Blue Sky Press.

Bang, Molly. 1997. Common Ground: The Water, Earth and Air We Share. The Blue Sky Press.

Rockwell, Anne. 2009. What’s So Bad About Gasoline?: Fossil Fuels and What They Do. Collins.

Rockwell, Anne. 2006. Why Are the Ice Caps Melting?: The Dangers of Global Warming. Collins.

“Voices from Standing Rock: Tokata Iron Eyes.” Acronym TV. www.youtube.com/watch?v=S2uubENv6MU

“Stories from Standing Rock.” Vogue. www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFjnudxcfv0

“LNG: Just Another Dirty Fossil Fuel.” Hike the Pipe! www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8CQ9Qrei3c

“Pipeline Spills, 1986Ð2016.” nittyjee. https://youtu.be/ywCqqhkiq0M