Preview of Article:

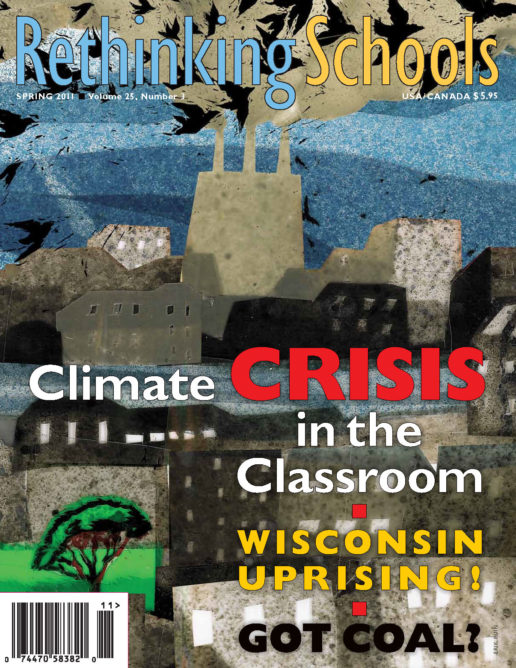

Got Coal?

Teaching about the most dangerous rock in America

In 30 years of teaching, I’d never taught explicitly about coal. Coal appeared in my social studies curriculum solely as a labor issue. We read passages about the 1914 Ludlow Massacre of striking coal miners and their families in Colorado, and watched John Sayles’ excellent film Matewan when we looked at early-20th-century labor struggles. But coal was mostly invisible in my history classes.

At the risk of sounding melodramatic, the world cannot afford this kind of curricular invisibility today. Forty percent of the main greenhouse gas produced in the United States, carbon dioxide, comes from burning coal for electricity; so does two-thirds of all the sulfur dioxide pollution. According to the American Lung Association, coal is responsible for 24,000 premature deaths every year. More than 50 percent of this country’s electricity comes from burning coal: more than a billion tons of coal every year—almost 20 pounds of coal burned each day for every person in the United States. And most coal mining in the United States these days is strip mining—the earth is essentially skinned alive to get at the coal seams within. Coal companies have sliced the tops off 500 mountains in Appalachia and dumped the waste in the valleys, burying 1,200 miles of streams and poisoning residents’ water. The term for this is mountaintop removal, and it’s not a metaphor.

So I decided that it was time to break my curricular silence on coal. Now that I no longer have my own high school classes, my friends and colleagues Tim Swinehart and Julie Treick O’Neill invited me to help them co-teach a piece of a unit on climate change and energy to their 9th-grade global studies classes at Portland’s Lincoln High School. (Tim and Julie teach separate classes but plan together.)

Coal is hidden—in the curriculum, but also literally: We encounter coal every time we turn on a light, but—at least in urban areas—our students almost never see it. I wanted to begin our brief introduction to coal by showing some of the stuff to students, but it was almost impossible to find. I sent an email to the 60 teachers on our Earth in Crisis curriculum list asking if anyone had any coal. No luck. So I called Portland General Electric, which runs Oregon’s only coal-fired power plant, in eastern Oregon. PGE promised to send me some coal but never did. Finally, I called several coal companies around the country and left messages. A few days later a package postmarked St. Louis arrived from Peabody Energy, the world’s largest coal company. Eureka. It contained a little baggie of chunks of coal.