G.I. Bill Doesn’t Vouch for Vouchers

Proponents of educational vouchers have cleverly packaged their proposals in language that makes them sound like irrefutably good policy. Labeling such proposals “choice,” for instance, suggests an expansion of options and opportunities that obscures the inequities built into them. Even more powerful than “choice,” however, is the common practice of touting vouchers as a new G.I. Bill. Former President Bush’s federal voucher plan was called a “G.I. Bill for Children,” and advocates of state-level voucher plans invariably use similar language. The association of vouchers with the G.I. Bill, in fact, has a history that traces to the writing of Milton Friedman, the conservative economist who made the first modern case for vouchers back in the mid-1950s.

Although Friedman did not press the analogy as far as recent proponents, the comparison always has served to cast vouchers in the radiance of universally popular legislation that did indeed massively broaden educational opportunity following World War II.

Current advocates of vouchers claim that the provision of a stipend to each child for redemption at the public or private school of a family’s choice will resemble the G.I. Bill and have similar consequences. It will improve the overall quality of education by forcing public institutions to compete for students with private ones; it will extend to families who currently can’t afford private schools the same opportunities that the well-to-do possess; and by directly aiding parents it will make government subsidized enrollment in parochial schools constitutionally allowable. These comparisons, however, distort the nature of the G.I. Bill and make inappropriate connections between that bill and school voucher initiatives. Indeed, the G.I. Bill no more resembles current voucher proposals than the G.I. series resembles a test for herpes.

Flawed comparisons begin with a failure of analogy-makers to recognize the intent of the G.I. Bill and to adequately account for its consequences. Most advocates of the original G.I. Bill were not interested in education perse. Fearing the potential for social unrest spawned by many thousands of unemployed veterans, proponents of the G.I. Bill viewed its educational program as a way of keeping former soldiers out of a labor market considered incapable of absorbing them. Essentially irrelevant to primary and secondary education, the bill did have a highly beneficial effect on higher education. But the betterment of colleges and universities was not intended, nor was it fundamentally accomplished through competition over students. Rather, the G.I. Bill stimulated a vast increase in applicants following World War II, which resulted in more than enough new students to go around. As of 1947, according to history professor Keith Olson, veterans composed 49% of college students, and their presence allowed dramatic growth in enrollment at many institutions.

Nonetheless, competition over students did thrive among proprietary schools, a high percentage of which were newly minted with the hope of reaping bonanzas from the tuition-bearing former soldiers. The unethical practices of many of these for-profit enterprises provide little support for voucher advocates’ faith in market forces. In fact, the problem was great enough that the G.I. Bill was modified so that only institutions with state approval could redeem veterans’ stipends, and further oversight was exercised by the Veterans Administration. Even then, complaints about false advertising and high incompletion rates would persist through subsequent versions of the G.I. Bill.

The flourishing of higher education in the post-war era was not due to competition, but it was in part due to the enrollment of so many highly motivated, mature students who previously would not have had the means to attend four-year colleges. Olson has estimated that 20% of those who enrolled in colleges and universities could only have done so with the support of G.I. Bill funds. The enrollment of African Americans, in particular, rose dramatically.

Full-Tuition Grants

This expansion of opportunity was made possible by generous tuition grants and additional stipends that partly offset the cost of living. Initially veterans received $500 annually for tuition and expenses, along with $50 a month for a single person and $75 for a married couple. Although this sounds trivial in today’s dollars, in 1948, $500 paid all but $25 of Harvard’s tuition and was more than enough to pay the tuition of nearly all other colleges in the country.

In contrast, the modest grants proposed by current statewide voucher plans would only pay a fraction of the tuition at most good private schools. California’s Proposition 174, for example, would have provided vouchers of approximately $2,600 at a time when the average tuition of private schools was around $7,000. Had the voters approved it, the voucher program would have been a G.I. Bill in reverse that subsidized the tuition of the well-off, reduced the level of required state aid to public schools, and left the poor with few meaningful options.

Under the G.I. Bill, colleges prospered financially, since the bill vastly expanded the pool of those who could pay the cost of tuition and then some. It is hardly surprising that many colleges were able to increase their tuition and fees without fear of a diminishing student supply. In addition, the Lanham Act funded the construction of educational facilities required by the influx of veterans. Thus, colleges and universities were not expected to do more with less resources, as voucher supporters claim public schools should be able to do. On the other hand, it is the case that voucher schemes, like G.I. grants, would allow private elementary and secondary schools to raise their tuition.

This financial benefit to private schools, however, would be exacted at the price of placing even more of them beyond the reach of people without the money needed to supplement their vouchers.

A final argument of voucher supporters is that the G.I. Bill, which has allowed veterans to attend secular or non-secular colleges, demonstrates that it is constitutional for voucher programs to include parochial schools. Their contention is that no violation of separation between church and state exists as long as individuals rather than institutions are provided with tuition money. What is at issue here, however, is not so much who gets the money, but whether the primary effect of this government aid is to advance religious institutions.

Unless this long-accepted principle is rejected by the Supreme Court, the current proposal of Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson to include religious schools in the Milwaukee Parent Choice Program is unlikely to be found constitutional. This is because sectarian schools would become the chief beneficiary of the program, which is restricted to low-income students whose vouchers can only be used at private schools. On the other hand, it is too close to call whether the current Supreme Court would find constitutional an inclusive program, in which there would be vouchers for all children that could be redeemed at public or private schools.

Since the vast majority of post-secondary institutions are non-secular, the G.I. Bill has not fundamentally advanced the interests of religious institutions. But the issue is not merely a matter of numbers. The Supreme Court also makes distinctions between religious institutions at the collegiate level and those on the primary and secondary ones. In Tilton v. Richardson(1971), for instance, the Court found permissible government grants to religious colleges for construction projects used for secular purposes. Put briefly, it maintained that no excessive entanglement between church and state would follow from such a practice. In contrast to viewing parochial elementary and secondary education as being suffused with religion, it held that religious institutions of higher education typically resemble non-secular ones in their commitment to academic freedom, in the substance of their curricula, and in the employment of many faculty who are not affiliated with the religion of the college. Additionally, the Court pointed out that the greater maturity

of college students makes them far less subject to religious indoctrination than children. Thus, the Court concluded that for secular colleges there was “less danger … than in church-related primary and secondary schools dealing with impressionable children that religion will permeate the area of secular education, since religious indoctrination is not a substantial purpose or activity of these church-related colleges …”

A New G.I. Bill

That the G.I. Bill does not meaningfully resemble voucher proposals should be obvious. Yet there is value in considering what a new G.I. Bill would look like. One obvious approach would be to restore to the current G.I. Bill the high level of benefits veterans received under the original one.

According to Reginald Wilson of the American Council on Education, veterans today, among whom African Americans are significantly overrepresented, are eligible for benefits that have diminished to about 50% of college costs. This partly accounts for why nearly two-thirds of those who qualify do not participate in the program.

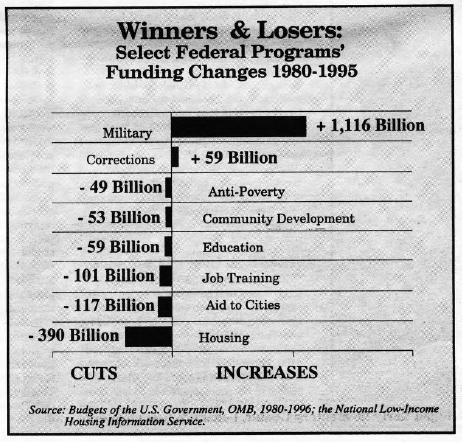

Not only would greater educational benefits attached to the current G.I. Bill expand opportunities to those of modest means, but even more far-reaching would be a major increase in the value of Pell Grants. Initiated by the federal government in 1972 to help low-income families pay the cost of college tuition, the value of these grants, according to TheNewYorkTimes, has declined approximately 15% since 1980, while the cost of tuition has risen some 50%. The increasing need to rely on loans is a major disincentive for low-income people to attend college. Remedying this situation obviously requires a significantly enhanced federal commitment to educational funding, the very opposite of the stance of conservatives who glibly conflate the G.I. Bill with vouchers.

The above proposals, like the original G.I. Bill, are clearly not meant to reform pre-collegiate education, and are no substitute for the need to transform schools that so frequently show contempt for the capacities of the poor in general and African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans in particular. But reinvigorated college scholarships would provide incentive for many low-income students to successfully negotiate high school as a means to greater opportunities beyond.