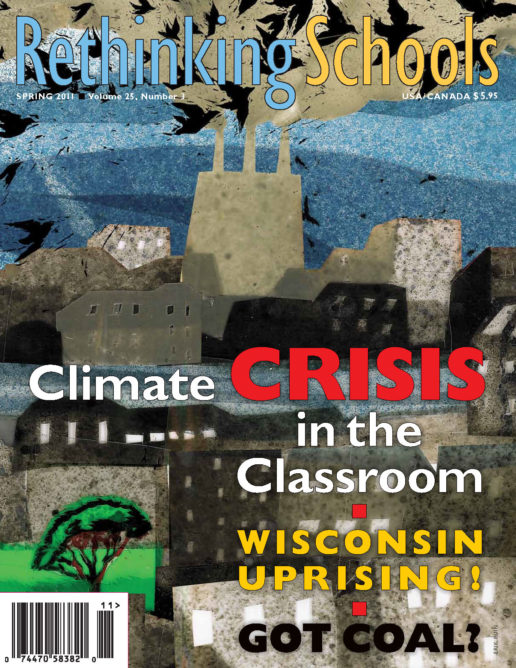

Preview of Article:

Fuzzy Math

A meditation on test scoring

Illustrator: Eric Hanson

As a public school English teacher, I observe standardized testing season each year with a sort of grim fascination. So this is it, I think as I pace around my silent classroom, peering over kids’ shoulders at articles about parasailing. Line graphs tracking the rainfall in Tulsa. Parts of speech. Functions of x. These are the 34 questions that will determine some aspect of my students’ futures, —as well as our school’s yearly progress report, my own teacher report card, and soon, possibly, my salary. I wince at my young charges’ careless mistakes. I see eyes rove. I know who came in yawning, who’s feeling sick, whose brother is back in jail. So many variables (input) producing a single-digit score (output). Functions of x.

Last month, several weeks after those long quiet mornings, I got another glimpse inside the testing industrial complex. Instead of reporting to my own school and teaching my 8th-grade writing classes, I reported to the gymnasium of a middle school uptown, along with 100-odd other New York City teachers, to score 5th-grade New York State math exams. I was there in place of a colleague, a special education teacher—as are the vast majority of the educators pulled out of schools to grade the state tests—who had already spent most of the prior week scoring reading tests and begged me to take her spot in “the warehouse.” (I should note that most standardized test scoring is done not by teachers, but by temp workers—who must possess at least a four-year college degree and are paid a low hourly rate.)

I arrived on the Upper East Side that Tuesday morning in a chilly May downpour, already on my second cup of coffee. Students with overstuffed backpacks jostled into the school’s double doors ahead of me, squealing about the rain. Inside, I headed toward the open gym door, where I could see 20 round tables, bedecked in red and blue plastic tablecloths. Clusters of damp-haired teachers were settling into the folding chairs, chatting quietly, leafing through newspapers. They were mostly young, in their 30s—some older and distinguished looking—with bright eyes, sensible footwear, books. This was no temp crew; these seemed like people who should be off teaching children. I took my seat among them.

After a spirited welcome sermon from the site manager, we scorers had to be trained. This involved several steps, starting with deciphering three pages of guidelines with stipulations like:

In all questions that provide response spaces for two numerical answers and require work to be shown for both parts, if one correct numerical answer is provided but no work is shown in either part, the score is zero. If two correct numerical answers are provided but no work is shown in either part, the score is one.