Fossil Food Consuming Our Future

I spend a fair amount of time thinking about how to reduce my family’s dependence on energy, particularly energy derived from fossil fuels. I commute to work by bicycle or bus, install compact fluorescents when light bulbs burn out, replace major appliances with the most efficient ones I can afford, and cast jealous glances at my friends who drive hybrids or alternative-fueled vehicles. But until recently, I didn’t think of myself as an energy glutton simply because of the food I eat.

Then I read an astonishing statistic: It takes about 10 fossil fuel calories to produce and transport each food calorie in the average American diet. So if your daily food intake is 2,000 calories, then it took 20,000 calories to grow that food and get it to you. That 20,000 calories of energy is embedded in the food. In more familiar units, this means that growing, processing, and delivering the food consumed by a family of four requires the equivalent each year of almost 34,000 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of energy, or more than 930 gallons of gasoline (for comparison, the average U.S. household annually consumes about 10,800 kWh of electricity, and about 1,070 gallons of gasoline).

In other words, we use more than three times as much energy to obtain our food as to fuel our homes (nearly as much as we use to fuel our cars). The power of this equation is especially revealing when applied to school lunch. According to 2005 USDA National School Lunch Program participation figures, 29.6 million American school children were served nearly five billion meals at school last year. Typically these meals are highly processed, filled with conditioners, preservatives, dyes, salts, artificial flavors, and sweeteners. Usually they’re individually portioned and packaged, and travel thousands of miles to the school cafeteria.

School meals are commonly delivered frozen, wrapped and sealed in energy-consumptive packaging, and in need of some interval in a warming oven to thaw before being served to students. Studies of packaging and plate waste in school cafeterias indicate that, every day, as much as half, by weight, of these hasty, unappetizing, low-nutrient, highly processed and packaged meals is tossed by students — unopened, unappreciated, untasted, unrecycled, and uncomposted. The energy needed to collect and transport the waste generated by school lunch must also be added to the net energy embedded in the meal.

Overall, about 15 percent of U.S. energy goes to supplying Americans with food, split roughly equally between crop and livestock production and food processing and packaging. David Pimentel, a professor of ecology and agricultural science at Cornell University, has estimated that if all humanity ate the way Americans eat, we would exhaust all known fossil fuel reserves in just seven years.

The implications of agricultural energy use for the environment are disturbing. According to the Intergovern-mental Panel on Climate Change, agriculture contributes over 20 percent of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, including more than 20 percent of the CO2, 55 percent of the methane, and 65 percent of the nitrous oxide. In addition, our energy-intensive agriculture industry contributes substantially to soil erosion, loss of wildlife habitat, degradation of water quality from chemical runoff, and other adverse environmental impacts.

Much of the energy embedded in our food comes from growing grains that require further processing to be eaten. Producing a two-pound box of breakfast cereal, for example, requires the equivalent of burning half a gallon of gasoline.

When cereal is served for breakfast at school, it tends to come preportioned, presweetened, and shrink-wrapped in individual plastic bowls with a plastic-sealed set of napkin and utensils, a foil-sealed plastic cup of fruit in heavy syrup or another menu item, and a waxed cardboard carton of slightly sweetened fluid milk. This configuration of packaging and consumables is served up millions of times a day, five days a week, to our nation’s school children.

Eating high on the food chain has other severe implications. Eating a carrot or an apple gives the diner all the caloric energy in those foods, but feeding these foods to a pig in the production of meat reduces the energy available by a factor of 10. That’s because the pig uses most of the energy just staying alive, and stores only a fraction of the energy of the apple in the parts we eat. All told, it takes 68 calories of fossil fuel to produce one calorie of pork, and 35 calories of fuel to make one calorie of beef.

Interestingly, the path to reducing the energy intensity of the food system dovetails nicely with the path to a healthy and nutritious diet. It also fits with educating our children for a future worth living on a tolerable planet. It can be summarized in three simple suggestions.

First, eat lower on the food chain. That means eating more fruits and vegetables, and fewer meats and fish. Meats, poultry, and fish contain necessary proteins, but most American diets contain too much protein — about twice the recommended amount. Since about 80 percent of grain production currently goes to feeding livestock, the amount of energy used indirectly to support our diet of double bacon cheeseburgers is staggering. If you eat meat, then try to avoid animals grown in feedlots or factory pens. They take far more energy calories to raise than do free-range, grass-fed critters, which have only about a third of the embedded energy.

Second, eat more fresh foods in their whole state, and fewer processed foods. Fruits and vegetables, but also whole grains, legumes, and other less-processed foods, have much less embedded energy. In general, the more packaging, the more processing — and the more energy associated with its production.

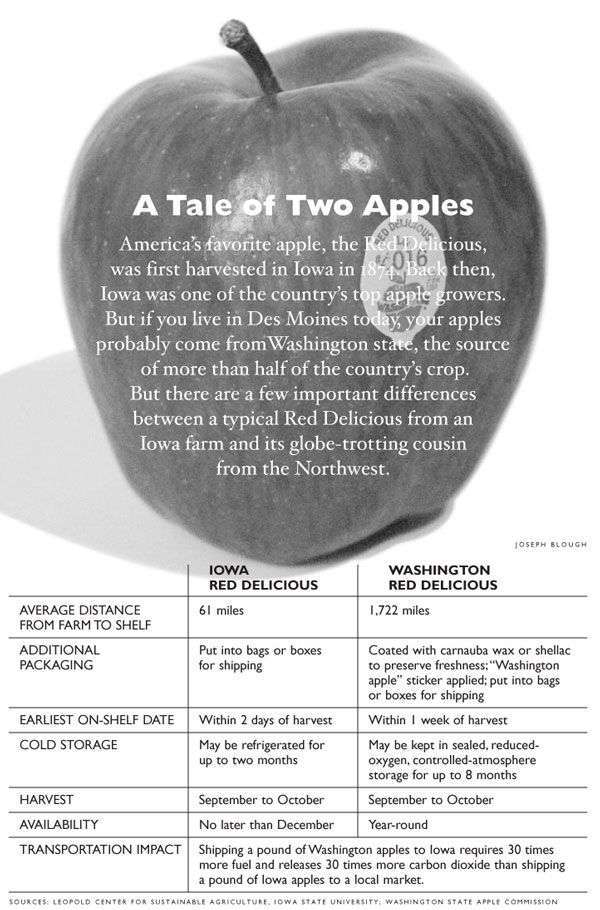

Third, buy local. Incredibly, the typical food item on U.S. grocery store shelves has traveled an average of 1,500 miles. And some foods are much worse. Table grapes grown in Chile, transported by ship to California, and shipped by truck to Iowa have traveled over 4,200 miles. In response, some agricultural scientists have proposed ecolabeling programs based on CO2 rankings or broader life-cycle assessments.

These analyses provide better information than just miles traveled. For instance, because they travel by air rather than by ship, Hawaiian pineapples are among the most carbon-intensive of foods, contributing about 40 pounds of CO2 per pound of pineapple. That is about 10 times the next highest figure among the foods studied.

Farm-to-school programs that underscore local procurement of fresh, sustainably grown foods and school meals that emphasize whole ingredients cooked from scratch are systemic solutions that begin to solve problems in health, education, and the environment. In my hometown of Portland, Ore., individuals, schools, and businesses alike are starting to recognize and respond to the public’s concerns about fossil food. Grocery stores featuring locally grown and organic products are common. Farm stands, farmers’ markets, and community-supported agriculture operations are thriving. Here, even fast-food restaurants are turning to local and organic ingredients.

Supporting fresh, locally grown, minimally processed food through our school meal programs will help our kids lead healthier, happier lives. After all, every kid knows the expression: “You are what you eat.”