Fighting for the Truth

The Gulf War and Our Students

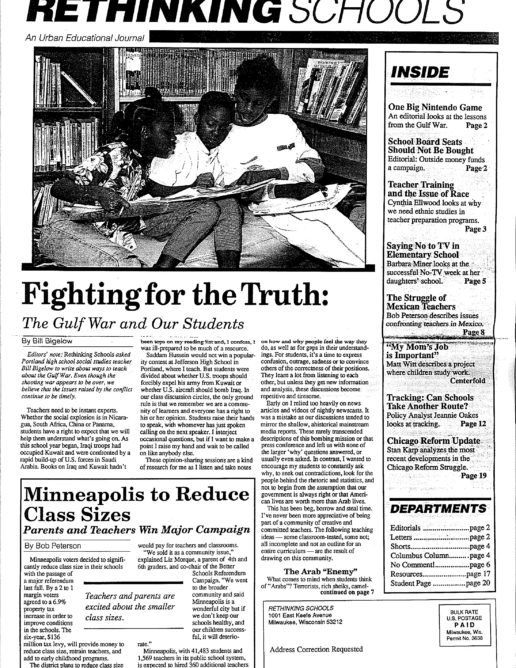

Editors’ note: Rethinking Schools asked Portland high school social studies teacher Bill Bigelow to write about ways to teach about the Gulf War. Even though the shooting war appears to be over, we believe that the issues raised by the conflict continue to be timely.

Teachers need to be instant experts. Whether the social explosion is in Nicaragua, South Africa, China or Panama, students have a right to expect that we will help them understand what’s going on. As this school year began, Iraqi troops had occupied Kuwait and were confronted by a rapid build-up of U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia. Books on Iraq and Kuwait hadn’t

been tops on my reading list and, I confess, I was ill-prepared to be much of a resource.

Saddam Hussein would not win a popularity contest at Jefferson High School in Portland, where I teach. But students were divided about whether U.S. troops should forcibly expel his army from Kuwait or whether U.S. aircraft should bomb Iraq. In our class discussion circles, the only ground rule is that we remember we are a community of learners and everyone has a right to his or her opinion. Students raise their hands to speak, with whomever has just spoken calling on the next speaker. I interject occasional questions, but if I want to make a point I raise my hand and wait to be called on like anybody else.

These opinion-sharing sessions are a kind of research for me as I listen and take notes on how and why people feel the way they do, as well as for gaps in their understandings. For students, it’s a time to express confusion, outrage, sadness or to convince others of the correctness of their positions. They learn a lot from listening to each other, but unless they get new information and analysis, these discussions become repetitive and tiresome.

Early on I relied too heavily on news articles and videos of nightly newscasts. It was a mistake as our discussions tended to mirror the shallow, ahistorical mainstream media reports. These rarely transcended descriptions of this bombing mission or that press conference and left us with none of the larger ‘why’ questions answered, or usually even asked. In contrast, I wanted to encourage my students to constantly ask why, to seek out contradictions, look for the people behind the rhetoric and statistics, and not to begin from the assumption that our government is always right or that American lives are worth more than Arab lives.

This has been beg, borrow and steal time. I’ve never been more appreciative of being part of a community of creative and committed teachers. The following teaching ideas — some classroom-tested, some not; all incomplete and not an outline for an entire curriculum — are the result of drawing on this community.

The Arab “Enemy”

What comes to mind when students think of “Arabs”? Terrorists, rich sheiks, camel-riders? Where do our earliest lessons about Arabs come from? In our neighborhood video store, my co-teacher, Linda Christensen, located an extraordinary example of the stereotyping of Arabs — a cartoon titled “Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.”

In the cartoon, Popeye, a member of the U.S. Coast Guard, is dispatched to the Middle East where the cutthroat bandit, Abu Hassan, terrorizes towns and villages with his gang. Popeye is clean shaven, resourceful, and fearless. Abu Hassan is bearded, dark-skinned, burly; he rides through the desert with his band trailing behind, waving his saber and singing, “Now make no error, I’m called the terror of every village and town — Abu Hassan!” Plainly, he is evil — and stupid. All his men wear turbans and are indistinguishable, one from another. In cartoon-land, Arabs speak a little English, but mostly gibberish.

When Abu Hassan raids the town where Popeye is staying (along with Olive Oyl and Wimpy) the townspeople offer no resistance and hide from the bandits. Popeye fights, loses this first encounter (Abu Hassan fights dirty) and Abu Hassan and crew steal everything not nailed down, including Olive Oyl.

Popeye trails the thieves to their hide-away and, upon seeing the wealth Abu Hassan has plundered, announces, “I have to give all these jewels back to the people.” Meanwhile, Olive Oyl scrubs the clothes for Abu Hassan’s turbanned look-alikes.

Popeye confronts Abu Hassan, they fight, he eats his spinach, and to the martial melodies of John Philip Sousa, Popeye defeats the thieves. As promised, the Americans deliver the stolen loot back to the cheering townspeople. The end.

The cartoon portrays the Arab masses as helpless, uninteresting victims, terrorized by heartless thugs. The prognosis is grim, save for the presence of justice-loving, militarily potent Americans, in this case represented by Popeye. As they watched, my students listed how men’s and women’s roles were depicted and how Arabs were portrayed.

Following the video, I asked them to write on what this cartoon might teach children. As always, students make connections that I miss. I’d noticed the lack of Arab women, but Kristina drew implications I hadn’t considered:

The Arabs are portrayed as dirty, mean, thieves and murderers, stupid. Plus they all look alike, no originality. Those are the thieves, and then there’s the peasants who are also portrayed as stupid, but they are also showed as cowardly and weak. The main thing I noticed is there’s no Arab women in this cartoon, like the Arabs have no gentleness, or beauty, and that’s very stereotypic.

Aashish:

Teaches children that sheiks from the Middle East are terrorists and USA is the best.

Michael:

Arabs are all the same people who wear headdresses and diapers; dark, shady, bald headed little bearded twerps who only use camels for cars, hide in vases, speak in an undesirable language and are spindly and have no musical talent. Most importantly, the U.S. has always been able to beat them down and we’re in the right.

Portland teacher, Eddy Shuldman, showed the Popeye video twice to her students. The second time she asked them to imagine they were Arab children and to write about how the cartoon would make them feel.

Whether or not one is able to locate this cartoon, it would be valuable to find some media through which students might explore attitudes about Arabs and the Middle East and how these attitudes can lead us to certain understandings, or misunderstandings, about today’s crisis.

I followed up with slides from a trip I’d taken to Jordan, the West Bank, and Gaza. It was a way of introducing students to the Palestinian/Israeli struggle, but also erased the cartoon Arabs from students’ minds and replaced them with real people: doctors, teachers, pharmacists, students, community organizers. We also read a short story by a young Palestinian-American student, Johara Baker, “A Day Among the People,” which exposed students to the history and anguish of Palestinians in West Bank refugee camps. The goal was to give voice and persona to a people too often depicted as the inferior, inscrutable “Other.” Kuwait University professor Shafeeq Ghabra’s “The Iraqi Occupation of Kuwait: An Eyewittness Account,” (Journal of Palestine Studies, Winter 1991) could also be excerpted for use with students. Ghabra’s is the best account I’ve seen to paint a human portrait of the degradation and brutality visited on Kuwaitis by the occupying Iraqi army. His account also chronicles the determination and creativity of the Kuwaiti resistance.

Exploring policy contradictions

Why is the United States involved in this war? An answer is beyond this article’s scope, but one way to approach the question is to test official explanations against past U.S. conduct. Such a route might also lead students to a broader understanding of U.S. foreign policy.

At the date of this writing, February 25th, there have been numerous statements by President Bush, Secretary of State James Baker, and others about the objectives of U.S. involvement in the Middle East. Students remember most of these and we list them on the board. At first the mission was to protect Saudi Arabia from the alleged possibility of an Iraqi invasion. Soon, talk turned to the “liberation of Kuwait” and the “restoration of its legitimate government.” Later objectives were to protect “our way of life,” and American “jobs.” Another oft-stated goal was to destroy Iraq’s nuclear, chemical, and biological warfare capacities, in fact, obliterating its war-making abilities. More recently, President Bush spoke of creating a New World Order.

A constant refrain is that Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait is intolerable because it violates the U.S. principle of support for national sovereignty — a principle underscored by numerous UN resolutions. To test U.S. commitment to this principle we should explore with students how the United States responded to other invasions and occupations.

Nicaragua:For fifty years the United States supported the Somoza family dictatorship in Nicaragua — “He’s a sonofabitch, but he’s our sonofabitch,” FDR was reported to have said about Somoza.

Decades later, during the U.S.-financed contra war against the Sandinista government, the United States had no use for the United Nations. In April 1984, Washington rejected World Court adjudication of U.S. disputes with Nicaragua, although the United States’ refusal was a direct violation of the UN Charter. When the World Court ordered the United States to halt its aggression against Nicaragua in 1986, the Reagan administration ignored the ruling. What accounts for the different response to Iraq’s aggression?

Israel:During the last 15 years, the UN Security Council adopted 11 resolutions condemning Israeli aggression against Lebanon and other Arab countries. In August 1980, the Security Council declared Israel’s annexation of Jerusalem “null and void.” In December 1981, the Security Council declared Israel’s annexation of the Syrian Golan Heights “null and void.” In December of 1982, a General Assembly resolution deploring Israel’s invasion of Lebanon passed 143 to 2 (the U.S. and Israel). Earlier the General Assembly had condemned Israeli settlements in the Occupied Territories as “a serious obstruction to achieving… peace in the Middle East.” Three Security Council resolutions demanded Israel’s immediate withdrawal from Lebanon. The General Assembly has repeatedly criticized Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. A 1989 resolution was affirmed 151 to 3 (U.S., Israel, and Dominica).

One might ask which principle is upheld when Israel is rewarded with between $3 and $4 billion annually in U.S. aid while Iraq is hit with “smart” bombs and B-52s?

[For high school students and our own background, I recommend Norman Finkelstein’s “Double Standards in the Gulf” in the November 1990 issue of Z Magazine(150 West Canton St., Boston, MA 02118). Middle and elementary teachers could also work with the information in the article.]

Namibia: UN Security Council Resolution 435, passed in 1978, demanded UN-supervised elections in Namibia to choose a constituent assembly leading to an end to the illegal South African occupation. For years, the U.S. government sat on its hands as Newmont Mining, Amax, Texaco, Standard Oil of California, and other U.S. companies exploited the colony’s mineral wealth. Moreover, when South Africa invaded and occupied southern Angola in 1981, the United States vetoed a UN Security Council resolution condemning the invasion. Does U.S. intervention depend on the race of those whose rights have been violated? Perhaps the $2.5 billion U.S. corporations had invested in South Africa by the early 1980s factored into our non-response.

Rhodesia: In 1968, the UN Security Council approved mandatory economic sanctions against the racist white minority regime in then-Rhodesia, the first comprehensive sanctions ever imposed by the UN. Did the United States wait a few months for the sanctions to work and then propose military action? No. In 1971, the U.S. Congress called for the importation of Rhodesian chrome — joining Portugal and South Africa as the only countries officially violating the sanctions.

Iraq: Before his invasion of Kuwait, Saddam Hussein was, like Nicaragua’s Somoza, our sonofabitch. As Hussein prosecuted a bloody war against Iran, the United States government provided him with military intelligence, aid, and favorable trade terms. Despite evidence his army used poison gas against the Kurds in the north of Iraq, the United States continued its aid. But after his invasion of Kuwait, with its close ties to the West, Saddam Hussein stopped being our pal. As the New York Times’ Thomas Friedman recently remarked, in the eyes of U.S. policymakers, before the invasion Saddam was “our thug and our bully…a bulwark against these wild, crazy, and uncontrolled Iranians.”

Principles? What are they, when are they invoked and when are they ignored? These are vital questions to raise with students. Without doubt, Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait was illegal and brutal. But because the United States has not responded with equal force and decisiveness to other illegal and brutal occupations, students need to probe more deeply to discover the source of our current intervention in the Gulf.

Who benefits?

A key question I raise with students as we walk — sometimes stumble — down the road to understanding U.S. intervention in the Middle East is: who stands to gain?

Together, students and I brainstorm a list of beneficiaries from U.S. involvement in the Gulf.

Students know that maintaining control of “our” oil is a factor, but intuition tells them it must be more complicated. I think it is. In fact, the major export of Kuwait is not oil but money; money that’s invested mostly in Great Britain and the United States. The major source of Kuwaiti income is interest on the money invested in the West — which, of course, ultimately does come from oil. The Kuwaiti elite has a direct stake in the Western economies. By contrast, Iraq made no such massive investments in the West and there was no assurance that it would use its new-found oil treasure to strengthen Western economies. Who stands to gain from the installation of Kuwait’s former rulers? Certainly the Kuwaiti elite. But in a larger sense, Western capitalists, seeking to re-establish the investment status quo from which they benefited.

The peace movement likes to ask rhetorically, “What if Kuwait’s major product were broccoli?” The implication is that, were this the case, U.S. troops surely would not have intervened. No? The U.S. government intervened by proxy in Nicaragua (major product: poverty, with a little coffee and cotton thrown in); conspired to overthrow the Guatemalan government in 1954 (major product: poverty and bananas); has poured $4.5 billion to prop up a repressive regime in El Salvador (major product: poverty, cotton and some coffee). The list goes on. These interventions appeared not to aim at control of a valuable resource, but at maintaining each country’s compliance with the wishes of U.S. policy makers.

Winner: those who benefit from existing power relationships.

In the Middle East, the elites of Saudi Arabia and the other emirates benefit from U.S. intervention as, at least for the moment, U.S. force insures the stability of the Gulf oil monarchies. Ironically, despite the damage and terror caused by Iraqi Scud attacks, Israel also stands to gain from the war: the Iraqi military threat is destroyed; international sympathy for the Palestinians wanes; war promotes increased divisions in the Arab world; the country rebuilds the underdog reputation tarnished by its suppression of the intifada and can lay claim to even more U.S. aid. In late February, for example, the U.S. approved $400 million in housing aid to Israel that had been stalled for several months.

The U.S. arms industry wins big. Peace is bad for business and the fall of the Berlin Wall sent shudders through the board rooms of military contractors. With half a million troops in the Persian Gulf, we no longer hear about a “peace dividend.” As military industrialist Jim Roberts said recently to the cheers of his audience at the 5th annual Defense Contracting Workshop in Milwaukee, “Thank you, Saddam Hussein.” The list can go on and students sometimes get carried away listing yellow ribbon manufacturers, flag sellers, political button dealers and other small-time war profiteers. The point is that from seeking beneficiaries of U.S. intervention our students can begin to make hypotheses about the source of that intervention. Students need to develop their capacities to make explanations in order for them not to settle for or be swayed by slogans. Arriving at the “right” answers — whatever those may be — is less important than engaging students in the process of probing beyond mere description.

Listening to media silences

I ask students where they get their news. We list the sources on the board: NBC, CBS, The Oregonian, Newsweek, etc. I point out that these entities are owned by huge corporations. NBC, for example, is owned by General Electric, the tenth largest U.S. corporation and a major war contractor. [See Ben H. Bagdikian, The Media Monopoly, Beacon Press.] This raises important questions: What stories might these media be reluctant to pursue? What might they be unlikely to criticize? How does the quest for profit influence the character of a news show — say, Peter Jennings’ “World News Tonight” on ABC (owned by Capital Cities, yearly after-tax profits in the $450 million neighborhood)?

Students can brainstorm on the topics they’re not hearing about. For example, as late as two weeks after the U.S. began bombing Iraq and Kuwait, one of my students asked, “What’s happening to the Palestinians in all this?” I too hadn’t seen any network news story on the Palestinians, though I had heard a Pacifica Radio report that Gaza and the West Bank were under “curfew” — a sanitary description of round-the-clock house arrest with two-hour breaks every few days to buy food. A colleague is teaching at a university in Egypt this year, so I was also aware of the lack of coverage of the grassroots response in Egypt and other Arab countries to the allied bombing of Iraq and Kuwait.

In small groups, students might imagine themselves producers of a non-corporate sponsored news show: What do people need to know to make decisions about supporting or opposing the war? How should the anti-war movement be covered? (A recent survey by Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting, a media watchdog group, found that in the first five months of the crisis, the networks had devoted only 29 minutes of 2,855 total minutes of Gulf coverage to opposition to the U.S. military buildup.) What “silences” need to be filled in network coverage of Middle East events? Which questions are the media pursuing (“How many bombing sorties were there today? What weapons systems have been employed in the ground war?”) and which questions are they ignoring (“What principles really guide U.S. foreign policy? How is Kuwait tied in to the world economy?”) Students would need to ask themselves what is “news;” is it entertainment or education? If education, for what purpose? As alternatives to mainstream coverage, we might bring to class smaller circulation, non-corporate journals like The Nation, In These Times, The Progressive, Z Magazine, The Guardian, or Middle East Report.

The other evening, on Portland’s local cable access channel, I watched a series of anti-war programs produced by the Gulf Crisis TV Project for Deep Dish TV [339 Lafayette St., New York, NY 10012, (212) 473-8933]. The shows gave me a new appreciation of the pro-war bias of the networks — how inherently limited is the media’s obsession with describing the war rather than explaining it. Project reporters interviewed articulate critics like Palestinian scholar Edward Said, MIT Professor of Linguistics Noam Chomsky, journalist Molly Ivins and anti-war activist Daniel Ellsberg, who were allowed to offer more than a one sentence quip. Each episode also featured anti-war demonstrations, with a broad range of tactics. Excerpts from these videos might prompt students to question the silences of the corporate media on key issues.

Students as journalists

When I teach the history of the Vietnam War, I play Lyndon Johnson and deliver a 1965 defense of U.S. involvement. Unlike President Johnson, in this role play I allow students-as-reporters to grill me in a press conference following the speech. For homework, students write an account of the speech and press conference as if they were reporters for different newspapers ranging from conservative (a small town Oregon paper, the Bend Bulletin) to establishment (The New York Times) to left-liberal (I.F. Stone’s Weekly) to radical (The Guardian).

The goal is for students to see that news is “political.” Which facts are included, how they are arranged, who is quoted and who is not, what broader questions are raised — consciously or not, a reporter’s political perspective, and that of the journal for which he or she writes, determines the scope and slant of a story. As students listen to each other’s very different news articles describing the same event, they experience this first-hand. Afterwards, we look at how each of these publications actually covered Johnson’s speech.

The structure of this lesson could be adapted to today’s events, with students questioning “George Bush,” after a dramatic reading of, say, parts of his State of the Union address, then afterwards reflecting on and recording the results. Including a “Saddam Hussein” in the press conference would point the lesson in a different direction, but could also be useful.

Doublespeak: The language of war

At a recent press briefing, Gen. Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said in reference to the Iraqi army in Kuwait, “First we’re going to cut it off, then we’re going to kill it.” Another military press spokesperson said that Iraq was bombed so heavily because it was a “target rich” country. In press briefings, civilian casualties are referred to as “collateral damage.” A characteristic of the language of the military and those who report on the military is that humanity is buried in a prose of lifelessness. Gen. Powell, for example, could have been talking about a rat or a cockroach. News anchors report “targets” being “hit” or “pounded” and “the enemy” attacked. The reality behind this antiseptic jargon is that human lives are being ended or altered forever — people aren’t things.

The language itself can become a political force in shaping our and our students’ understandings about the nature and conduct of the war. Edward Herman’s “Double Speak” column in Z Magazine is a wonderful resource to provoke students to critically read propaganda masquerading as news. Why, for example, is Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait labeled “aggression” but the U.S. invasion of Panama dubbed “Operation Just Cause”? According to Herman’s Doublespeak Glossary, the definition of “aggression” is, “moving armed forces into another country without our approval; also, providing aid and comfort to an indigenous uprising of which we disapprove.” Thus, by definition, under no circumstances can “we” ever be the “aggressors.”

Have you noticed how many politicians, military spokesmen, and reporters call Iraq’s invasion “naked” aggression?

Herman comments, “Aggression is a bad business, but calling it naked aggression means we intend to do something about it. Our own aggressions, in Grenada, Panama, the Dominican Republic, and Indochina, were of course properly clothed in a cloud of justifying rhetoric.” Why wasn’t South Africa’s invasion of Angola labeled “naked aggression”? Because we never had any intention of confronting the aggressor. We should ask our students: Why not?

English and social studies classes could pore over speeches, news conferences, and press releases reading for doublespeak.

They could function as truth detectives ferreting out duplicitous or obtuse statements and revising them with clarity and honesty as the criteria. Like Edward Herman, they could invent their own doublespeak glossaries. Or as they read they might talk back to and translate the writers’ doublespeak, paragraph by paragraph.

In my classes at Jefferson, we practiced with George Bush’s comment that he was going to kick Hussein’s ass. “Kick ass,” I said and wrote it on the board in big letters, “What exactly does that mean? When do you hear that expression?” Students suggested that kick ass might describe what a football or basketball team is going to do to its opponent or how badly a little boy is going to beat up another little boy. It implies a clear, unambiguous victory, winning — which took us into a discussion about what it would mean to “win” a war against Iraq: What then? We ended up with the possibility of a permanent U.S. force in Iraq, U.S. leaders in control of reconstructing Iraq’s political system, increased internal conflict in countries like Egypt and Jordan, no resolution of the Palestinian question, etc. Kids saw that to “kick their ass” was a bit more complicated than Trailblazers 125, Lakers 99.

People behind the numbers

War is more than numbers; it’s about people. Linda Christensen helped her students, through poetry, share their feelings and insights about the war’s human consequences. She began with a letter she’d received from an ex-student:

…There is this enormous hole that I can’t explain — somewhere between my heart and my brain — I can’t fill it with air-raids and tear gas…

I don’t know what to do with myself! I want to cry, to scream, to punch something!

I want to throw-up and get rid of everything. I can practically taste the bile on my lips — my stomach churns… and there is this enormous hole that even my children and the children after them will not be able to plug — it’s been chiseled away for years…

I’m scared, Linda. Really scared.

Linda then shared students’ poems about the Vietnam War and others from Vietnam veteran Yusef Komunyakaa’s book, Dien Cai Dau [“You and I are Disappearing,” “Prisoners,” and “Thanks”]. Students wrote down and shared war images they’d found disturbing. These became the seeds of poems or letters the students wrote.

Dyan Watson’s poem, “Gulf Games,” is reminiscent of the football metaphor that is a motif running through Hearts and Minds, the outstanding film on the Vietnam War:

I don’t remember when I received my first football

I can only see me and Dad in the backyard “throwing it around”

…[Dad] would run around in his old college uniform

ducking here

dashing there

tackling invisible peopleI always won of course —

no matter what the score was

When I made the school team

Dad was always there

cheering me on, praying for me“Go son, go!”

Cheer for me now, Dad

Pray for me.

For me, Dyan’s poem is a human side of the little x’s and o’s that the parade of retired generals are so fond of manipulating as they chart the missiles, bombers, and tanks on the network news every evening.

Action as antidote to cynicism

In Portland, there have been numerous high school and middle school student walkouts to protest the war. Students also joined the thousands of marchers in nightly protests after the bombing of Iraq began.

Some of my students have also attended “pro-troop” rallies — many of which explicitly supported U.S. intervention. Whichever side students take, I encourage them not to be spectators, but to be history makers.

The more we use our classrooms to analyze war, oppression, and exploitation, the more important it is to allow — even encourage — our students to act. To keep students’ passions and beliefs bottled up is to turn our classrooms into factories of cynicism and despair. Teachers may not be political organizers — it’s not our place to recruit for our favorite activist groups — but students must come to view themselves as agents of change, not objects of change. Hope should be the subtext of every lesson we teach — especially now.