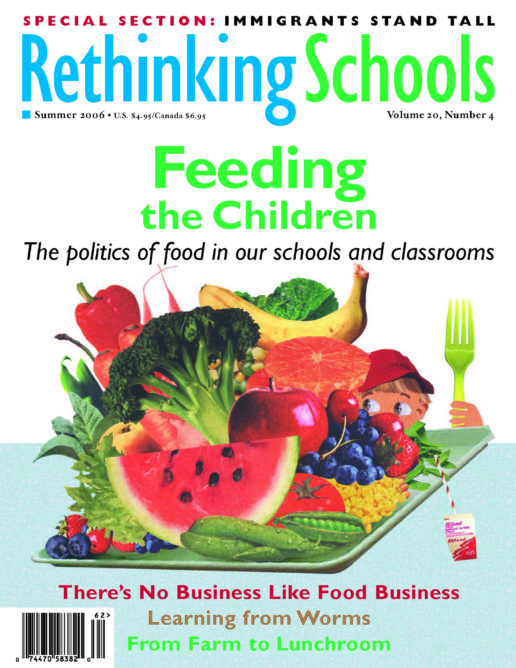

Feeding the Children

Illustrator: Randall Enos

“You are what you eat,” so the saying goes. Well, for years, schools have been feeding children some dubious ideas about food.

School cafeterias and classrooms are where many of children’s ideas about food are solidified. And in a culture dominated by corporate fast-food chains and large-scale corporate agriculture, many of those messages are profoundly unhealthy.

As obesity, diabetes, eating disorders, and other health-related problems spiral out of control for children and adults in the United States, it’s worth taking a closer look, at not only what goes into our students’ mouths, but also what goes into their minds regarding food.

In this special edition of Rethinking Schools, we take a look at the curriculum of food. And we mean curriculum in the broadest sense. We believe everything that goes on in school is curriculum, so we explore the messages our students are getting from the food they are served in the cafeteria, the vending machines, the barrage of advertisements, and the lessons we teach in the classroom.

When so much of the food that students encounter is transported over long distances, chemical-laden, shrink-wrapped, and processed, students make little connection with the foods’ origins. The process of discovering these origins is ripe curricular ground, as several articles in this issue explore. Students can investigate the biological and ecological processes, the labor (this includes immigration, globalization, and economics), the nutritional implications, and the health effects of the diets prevalent in this country. As the farmer and author Wendell Berry puts it:

I begin with the proposition that eating is an agricultural act. Eating ends the annual drama of the food economy that begins with planting and birth. Most eaters . . . ignore certain critical questions about the quality and the cost of what they are sold: How fresh is it? How pure or clean is it, how free of dangerous chemicals? How far was it transported, and what did the transportation add to the cost? How much did manufacturing or packaging or advertising add to the cost? When the food product has been manufactured or “processed” or “precooked,” how has that affected its quality or price or nutritional value?

We believe the questions Berry poses are worth exploring with students. After all, if they’re not taught to ask questions as essential as “What is this thing you’re handing me?” then the message they get is “Shut up and eat what society feeds you.” Food becomes the metaphor for a life where they’re expected to acquiesce in silence to their roles as passive consumers of food, advertisements, tests, education, wars, and work.

For students who are lucky enough to get their hands in the dirt — to plant, dig, compost, harvest, and share in the fruits of their own labor, the rewards are incalculable. But even for kids who don’t have those opportunities, learning to think about and question what they eat is one key to creating an active, informed populace.

Advertising Nation

Beginning at the earliest ages, our students are bombarded with messages to purchase and consume. From TV ads to vending machines to logo-infested products, they are continually asked to eat and drink and buy. Even drinking water, which should be a basic human right, is now bottled in plastic and sold from machines.

According to Sharna Olfman’s book Childhood Lost, the advertising industry in the United States spends more than $15 billion annually in direct marketing to children. Olfman quotes clinical child psychologist Susan Linn who writes, “The village raising our children is dominated by a culture of greed that has a powerful negative impact on all aspects of children’s lives. It’s unrealistic to think that staying cocooned within our classrooms, offices, or health centers is adequate to the task of mitigating the impact of marketing that targets children.”

At the same time young people are asked to consume, they are also receiving confusing messages about beauty and sexuality. While tall models with sunken cheeks and jutting shoulder blades represent an unattainable beauty standard, eating disorders like bulimia and anorexia plague our youth. According to the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, as many as 1 percent of adolescents have anorexia nervosa and 2 to 3 percent have bulimia nervosa. The incidence of these disorders has doubled since the 1960s and is increasing in younger age groups (it is seen in children as young as 7) and in diverse ethnic and economic groups. Though the reasons for these medical disorders are complicated, their prevalence underscores the unhealthy relationship people in the United States have with food.

Rethinking school food includes teaching children to critique food advertising: the vending machines that line the hallways; the ubiquitous cartoon characters that adorn every cereal box, yogurt carton, and tube of toothpaste; and the commercials that are directly piped into classrooms. According to clinical psychologist Katherine Battle Horgen, more than “eight million children, including nearly 40 percent of the nations’ teenagers, are a captive audience for two-minute commercials during each school day as part of the Channel One news broadcast. Nearly 70 percent of the ads are for food.”

Food and Equity

When we look at food through an equity lens, it’s clear that we cannot talk about food without referencing the vast inequalities in our society. Despite the fact that the United States, with 5 percent of the world’s population, consumes 40 percent of its resources, more than 29 million children in the United States live in low-income families and more than 13 million live in poor families, according to the National Center for Children in Poverty. For many of these children, the school lunches and breakfasts (as inadequate as they may seem) are their main source of nutrition. According to the U. S. Department of Agriculture, on average more than 17 million children participated in the free- and reduced-lunch program in 2005. While striving to improve the quality and nutrition of the meals schools serve, it’s important to preserve and improve these essential programs.

There is increasing evidence, too, that sedentary lifestyles in the United States are contributing to out-of-control rates of child obesity and diabetes. Yet high-poverty schools, under the gun to meet NCLB mandates, are slashing physical education programs and even eliminating recess in order to spend more time preparing for tests. Kids growing up in poverty have less access to sports teams and after-school activities that could keep them moving. Instead, according to Eric Schlosser in Chew on This, the average U.S. youth spends 25 hours watching television each week. “[D]uring the course of a year, the typical American child watches more than 40,000 TV commercials. About 20,000 of those ads are for junk food,” writes Schlosser.

Hope and Resistance

All over the country, there are signs of hope and resistance to the unhealthy, processed, packaged, agribusiness-dominated food model that so many of our students experience.

Under mounting pressure and the threat of lawsuits, the beverage industry announced in early May that it will discontinue selling soda containing sugar in all public schools by 2010. This will mean a scramble to rework the “devil’s bargains” that many school districts have made with beverage companies. But why wait until 2010? And why wait for the corporations to meet this “voluntary agreement”? Lawmakers in Connecticut voted to ban schools from selling regular and diet soda as well as sports drinks. That’s the kind of decisive action that should be taken all over the country. By allowing corporations to place vending machines in schools (selling soda, diet soda, water, sports drinks, chips, or candy) the corporations still benefit by developing brand loyalty while our students’ health suffers.

At the federal level, a mandate for all school districts to develop “wellness policies” could be an opportunity for parents and teachers to help guide districts into healthier eating and economic relationships. As Leah Penniman explains in her article about the Seeds of Solidarity program in Massachusetts, elementary schools in Orange, Mass., have set a goal of purchasing 20 percent of the fruits and vegetables from local farmers. This should boost the local farm economy and reduce the “ecological footprint” of the lunch program.

As part of what Alice Waters, founder of the Edible Classroom program in Berkeley, calls a “delicious revolution,” students all over the country are getting a taste of gardening and fresh, wholesome eating. At the Center for Ecoliteracy’s website (www.ecoliteracy.org) they document how classrooms, schools, and districts are moving toward direct connections with farmers, buying alliances, and farms. In this issue, we highlight two such programs, Seeds of Solidarity in Massachusetts and Wisconsin Homegrown Lunch.

In another encouraging move, groups that promote fair trade alternatives to race-to-the bottom globalization are moving their messages into classrooms and delving into the school fundraising arena. As long as parent-teacher associations need to sell products to keep schools afloat, they may as well sell products that are produced and traded fairly and support local economies.

Food provides some of the best examples of how teachers can develop curriculum that addresses the issues that shape our world, as several articles in this issue point out. By examining food in the context of fossil fuel consumption, neoliberal economic policies, and globalization, students can begin to understand both how powerful corporate agribusiness is and how their intimate, personal decisions (choosing what to eat) interact with the world that has been constructed for them. Many more teaching strategies can be found in Chapter 6, “Just Food,” of our book Rethinking Globalization: Teaching for Justice in an Unjust World.

It’s not “pie in the sky” to ensure that all children learn about the politics of food. We believe it’s incumbent upon all of us to begin to teach them about it — and to offer them a healthy choice.