Exploring Our Houses of Memories Through Poetry

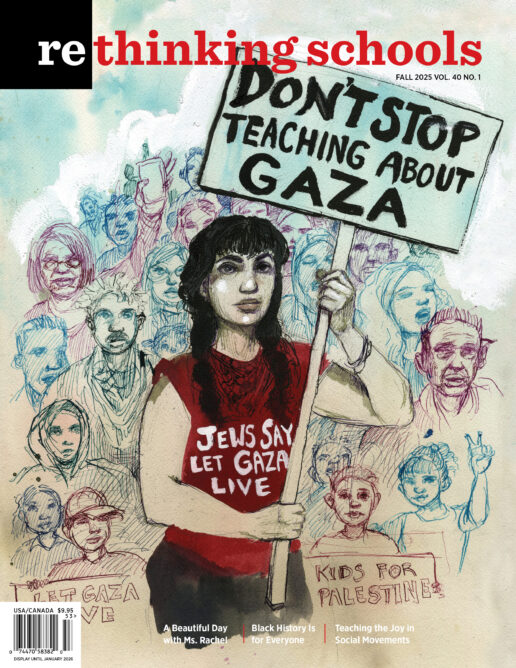

Illustrator: Sawsan Chalabi

Sometimes lessons provide a breath between units, a pause in the forward rush of the world. I attempt to write each morning. Although I miss this goal frequently, my daily routine reminds me that writing evokes memories, unfolding places, people, and times I have tucked away. For a few moments most days, I pull them out and savor them. Mom lives again in the early light of my kitchen. Pop smokes his pipe on the back deck. And my brother, Billy, grins, his black hair full and slicked back, ready to ride his Harley. Even writing about the pain and hardships I’ve experienced helps me look back and reflect on how these moments shaped me.

Students need this breath as well. At Grant High School in Portland, Oregon, where I nudged my way into Dylan Leeman’s sophomore class to co-teach, students take eight classes, four each day. The schedule is brutal. Students — and their teachers — need a break from the hurry-up, finish, move-on mentality. Poetry gives space for students to step outside of the rush and ponder their lives, the way I do most mornings.

I have used Natalie Diaz’s brilliant poem, “Abecedarian Requiring Further Examination of Anglikan Seraphym Subjugation of a Wild Indian Rezervation,” to encourage students to reflect about their lives and the world. Although I have attempted to harness the abecedarian poem, in which the first letter of each line or stanza follows the order of the alphabet, into a content-driven lesson, the poem always slides sideways from my plan. After giving up my original intentions to tie the poem to the “urban renewal”/Raisin in the Sun unit, I have embraced the way it opens writers to their own lives, their classmates’ lives, and their teachers.

To be honest, I fell in love with Diaz’s poem, which uses poetry and Biblical allusions to illuminate the way whites colonized and committed genocide on Native American people in the name of Christianity. After reading her book When My Brother Was an Aztec, I wanted to introduce her poetry to every group I worked with, so I developed this lesson to make that happen. Ultimately, I taught the poem to teachers in the Oregon Writing Project, to a class of high school students in a future educators’ class, to a Rethinking Schools writing cohort, and most recently to the sophomore class I co-teach with Dylan. Along the way, I discovered that the poem, unharnessed from content, moves some students into a space where they can still their mental chatter and uncover knowledge about themselves: their love of their language and culture, their anger at transphobia, their passion for travel, their connection to their grandmother’s trailer.

I discovered that the poem, unharnessed from content, moves some students into a space where they can still their mental chatter and uncover knowledge about themselves.

Examining Models

In my latest iteration of teaching the abecedarian poem, Dylan and I introduced students to Diaz: a brief bio on all her awards — Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, American Book Award, finalist for the National Book Award; her background as an enrolled member of her Gila River Indian tribe; growing up in Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California; her early career as a professional basketball player. We talked briefly about her work preserving her native tongue through the Fort Mojave Language Recovery Program, working with the remaining speakers of the language.

When Dylan and I distributed the poem, we asked students to listen and watch as Diaz recited her piece on a PBS weekly poem program. Students struggled with Diaz’s poem. The vocabulary, even in the title, presents difficulty. Many students are not familiar enough with Christianity to understand the idea of angels and the role of Gabriel, the messenger, or frankly with how colonization played out in history.

After students heard Diaz read her poem, we asked them to read it on their own and to make notes in the margin: “What words do you know? What words can you guess? What do you wonder? What is the poem about? What lines signal that? What confused you?”

Dylan’s classroom is arranged in eight table groups with four students at each table, and we have learned that these students worked best when they had time to talk through their ideas in small groups before we discussed them in the large group. The poem confused most students, but in the classroom discussion a few students ferreted out that it was about an Indian reservation — the opening introduction helped with that — and that the “angels” were like the whites who came “floating across the ocean” and stole Native American land.

Quit bothering with angels, I say. They’re no good for Indians.

Remember what happened last time

some white god came floating across the ocean?

Truth is, there may be angels, but if there are angels

up there, living on clouds or sitting on thrones across the sea wearing

velvet robes and golden rings, drinking whiskey from silver cups,

we’re better off if they stay rich and fat and ugly and

’xactly where they are — in their own distant heavens.

You better hope you never see angels on the rez. If you do, they’ll be marching you off to

Zion or Oklahoma, or some other hell they’ve mapped out for us.

Despite the hard work of teaching the poem, I will continue to use it. First, working through challenging text helps students persist when they come up against a piece they don’t understand. Not all the time, but often. Second, I wanted to introduce them to the abecedarian poetic format and understand that this is not the acrostic poem they learned in elementary school when they wrote about their name or their favorite animal. No insult to those lessons; they are age-appropriate, but by middle and high school, students need to develop their capacity to write in diverse forms with more complex ideas and language.

To make the poem more accessible, Dylan and I both shared abecedarian poems we had written. We wanted students to witness how we used the format with diverse topics. I wrote about my brother’s memorial service and teaching; Dylan wrote a beautiful poem, “A is for abecedarian and avocados,” which moves between acrostic and abecedarian formats about ICE detention centers and immigration:

Pilgrims

Questing for

Rest and

Sanctuary,

Tired and poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free

United States, you promised us a better life, a dream

V is for vámonos, Abuela; for vagar, to roam; for vallar, to fence in

W is where are you from?

X is for expel, exile, explode, like a dream deferred

Y is for Why?

Z is for xenophobic and for

zephyr, a breeze, may there always be one for those in a cage, for those sailing toward hope

Dylan and I also discovered Karenne Wood’s powerful poem “Abracadabra, an Abecedarian” that begins with a description of the not-there.org campaign that erased women’s images from magazine covers for International Women’s Day to call attention to the inequality women still face. Then Wood moves into a new section of the poem that addresses the disappearances and domestic abuse of women.

Now you see her. Not. Not-there. Not here, either,

or anywhere. Maybe only part of the problem is the predatory perpetrator-

prestidigitator who more often than not knows her, knows how to keep her

quiet, who may claim to love her, even, maybe getting even — or the serial

rapist-killer in the bushes who bushwhacks her in the dark. You’re always safe,

says the forensic psychiatrist, unless a monster happens to show up, and

then you’re not. Not-there. Maybe a lonely mandible, maxilla, fibula, or

ulna shows up, or a bagged body gets dragged from the river. Or not. Is this the

value we permit a woman’s life to have (or not-have) throughout a wrong

world, a global idea of her as disposable parts? In the end, this is not a

xenophobic poem, not specific — it’s everywhere. Not-there. Right here.

Yes, the sun rises anyway, but now the parents are staring past each other, that

zero between them like a chalked outline in their family photograph. Or not.

We used multiple diverse models to unlock the floodgates of possibilities for students: What was on their minds? What did they want to write about? Who did they want to write about? What issues in their lives did they want to address? What issues in the world?

“I tend to create lists, and my line breaks fall within similar cadences, even my vocabulary, unless I ransack other poets for their language my words eddy in the same currents.”

Teaching the Poem

After examining the models for content and style, we asked students to open their notebooks and brainstorm topics they might write about. “Natalie Diaz wrote about the reservation and colonization, Mr. Leeman wrote about Guantánamo and deportations, I wrote about teaching and my brother’s memorial. In your journal make a list of categories or topics, like politics — race, class, xenophobia, gender identity — but also think about family, sports, art. Leave room under the categories and then stack up some ideas under each one.”

Because we know students in our class play all kinds of sports, we started there: “Once you settle on some ideas, think about what words you might use. For example, what vocabulary would you use for football? Softball? Rugby?” We encouraged the same listing with art and cooking, modeling the category and then listing nouns and verbs as well as people’s names and locations. Because they had lots of content knowledge about gentrification and urban renewal from our previous unit, we lobbed out the idea of writing about that. No one took the bait. This building of word lists is important because the poem depends on the language of the topic. Students need a firm base of words to stand on when they begin writing their poems.

After students noted categories and vocabulary in their notebooks, we asked them to share in their table groups and help their classmates build out their lists: “What other nouns and verbs could you use? Are their names of people who could be brought into some lines? Julia Child? Jimi Hendrix?” We looked back at the way Diaz brings in people’s names and places. Some students shared their ideas in the large group, others sidled up to us wondering if they’d have to share their poem with the class because they wanted to write something private. We encouraged them to write with an open heart about whatever felt urgent and important to them in this moment without fear of sharing. Our collective years of experience have taught us that students will share their poems, even the private ones, with a partner, a small group, or, if the class feels safe enough, with the whole group. Those “private” poems, written with courage and honesty, have provided some of the best teaching moments of my career.

Once students committed to a topic, we encouraged them to experiment. As I talked about the poem with our class, I shared how this poetic form forced me out of my traditional patterns, making me reach for new language as well as new line breaks, but also tricked me into going places with my ideas and content that hadn’t even occurred to me when I started the poem, which is one of the benefits of the abecedarian — uncovering territory that may need to be explored, but which we rarely have time to ponder. “Often, as poets and writers, we have habits that we lean on and probably overuse,” I said. “I tend to create lists, and my line breaks fall within similar cadences, even my vocabulary, unless I ransack other poets for their language my words eddy in the same currents.”

Some students struggled initially, and as they wrote their first lines, the hushed sounds of the alphabet song could be heard around the room, warbling up from time to time as students reached a new letter of the alphabet for a new line. Although they wrote the poems in their notebooks, they also used their Chromebooks to look up vocabulary. Many leaned on their tablemates for ideas: This was not the quiet poetry workshop that I’d taught with adult writers. Sometimes after hearing a classmate’s idea, they abandoned their original topic and found firmer footholds with a new subject. Some students read lines or sections out loud as they asked classmates for a word or an idea. That said, quite a few found a stream of words and ideas and drank deeply and quietly as they wrote their poems. Others toughed their way through the prompt, but never really found their way into a piece that made them search their hearts, which is true of most assignments.

A few immigrant students, like Tommy, wrote about their homeland, especially the food, using the poetic format to bring in their home language: “A is for arroz con pollo . . . G is for grating the goat cheese, or el queso de cabra.” Nora and others wrote about places that felt like home, sometimes their own homes, sometimes grandparents’ homes or summer camps:

Joking and laughing in the

Kitchen with upside down

Light switches and linoleum floors

Maps and books covered the

Nude walls of me and my brother’s bedroom where we drew

Oceans and forests on furniture

Reading and hearing these poems reminded me that just as my morning writing recalls family and friends and places I have loved, students need to practice writing, but they also need to learn how to bring back memories of drawing on the wall, to live momentarily in a kitchen where families eat, relishing both food and language and laughter that erupts during gatherings.

Some students wrote pieces pondering their medical or mental conditions, gender identity, or the war that pushed their family to leave their homeland. Eli’s poem called out the accelerated attack on trans students, forcing them into silence and potentially death.

Abomination

Beast is what they

Call us

Death threats

Everyday

For no reason, using

God as an excuse, saying we’ll go to

Hell

In the end reason is long gone they

Just want to

Kill us

Like we

Mean

Nothing

Only thing we can do to

Please them is be

Quiet, to lie to

Rest, to

Shut up

They want us to become

Uniform, to

Vary no more, become like a

Whistle in the wind, like the chime of a

Xylophone

You say you help but when

Zir dead, when she’s dead, when he’s . . . dead where were you?

—Eli Niehus

Eli’s poem spells out the danger, the degradation, the threats on trans lives with phrases like “death threats,” “go to hell,” “kill us,” but he also urges against compliance, against the administration’s desire for uniformity, for silence, for trans people to “become like a/Whistle in the wind, like the chime of a/ Xylophone.” Eli’s poem reminds me of the reason students need assignments that allow for their rage and anger, as well as their love for Chilean food and light switch memories of home.

One of my goals as a language arts teacher is to unwrap the content of students’ experiences that are rarely allowed to be part of the classroom curriculum so they can embrace the fullness of their lives, while they also learn to use writing to explore the house of their memories. And while this abecedarian poem provides a pause between longer units in sophomore English, make no mistake about the seriousness of the assignment. Poetry teaches craft lessons: the careful sifting of nouns and verbs to find the just-right words, the dance of line breaks, the use of metaphor and allusion, the awakening to the way that writing is not just the province of published writers, but a tool that we can all use to make sense of our lives and the world.

As I wrote in my abecedarian poem:

Poets aren’t born; they’re built,

quilted together with words for seams.

Rhymes and rhythms, hymns and

stories spill like scrabble tiles across our room until our

talk stands within hailing distance of religion and hope and love.

Urgent

verbs jostle, lash out, question, argue, fight on the page

Wordsmiths flood their paper, ink and tears running together. Laughter is there too.

“‘Xactly,” I say. “No one can tell your story, but

you. We’re here. We’re waiting. There are no

zeros in poetry.”