Exploring Child Labor with Young Students

They can understand a lot more than some people might imagine

Illustrator: David L. Parker

-photo: David L. Parker

“I have something to share,” announced Kaya, as she proudly unfolded a piece of paper titled “The Pants and Shirt List.”

“I took out all my clothes and looked at the labels. I wrote down where they were made.” With some help with pronunciation, she read off her list. Out of 30 items of clothing, only three were made in the United States. The others were made in Asian or Latin-American countries such as Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, the Philippines, Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

“Most of them were made in Asia,” she said. When I asked her why she thought so, she said, “I think a lot of poor people live there.”

Juan Pedro was straining his hand to be called on.

“And the companies can pay them just a little and then the companies get more money!”

After years of thinking about doing a unit on child labor, I had finally taken the plunge. Other years I had hit on the topic when teaching about children’s rights or migrant workers, for instance, but until now I had not put a whole curriculum together on the subject for my multi-age second and third grade classroom. This year, inspired by a friend, Mary Modaff, who created a unit on child labor for her 4/5 classroom and by my student teacher, Kat Findley, I worked with Kat to pull together resources and brainstorm activities.

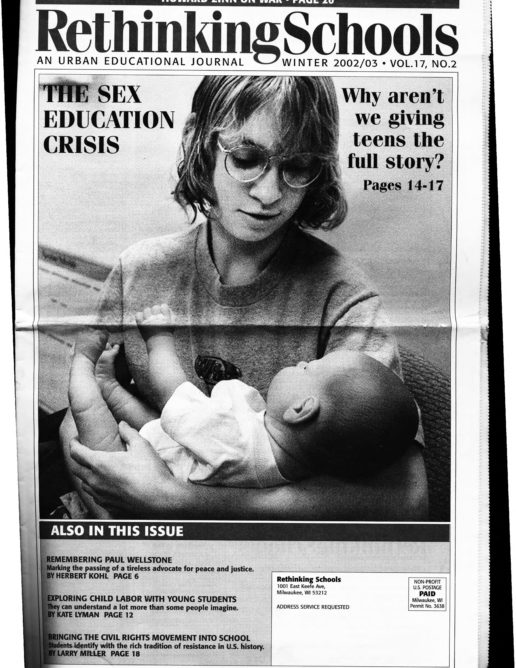

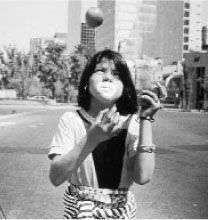

Like most people from the United States, my first images of children working were kids who got up early to help milk cows or feed the chickens on a family farm, young teens who babysat to earn extra money, or high school students who worked at fast food restaurants. My perceptions of children working expanded on my first trip to Mexico, where I saw young children selling chiclets in the town square and others trying to make a few pesos on the beach by offering anything from mango slices to a song-and-dance performance to the tourists. I admit that I thought these children’s efforts at making money were quaint and rather endearing until I ventured past the tourist strip to witness the poverty of their living conditions: cardboard and tin shacks facing dirt streets where children ran through dank sewage water.

-photo: David L. Parker

On subsequent trips to Mexico, El Salvador, and Guatemala I saw more of the darker side of children working: young girls up at 5 a.m., carrying bricks on their heads up a steep hill to a building construction site and teenagers working long hours in the maquilas without basic rights like bathroom privileges or sick leave. Finally, in Nepal, I saw some of the many children who spend their childhood toiling under the hot sun breaking up the rocks in stone quarries to make gravel.

As a teacher, I wanted my students to be able to understand this dark side of child labor, how different these children’s lives are from theirs. I hoped that they would develop empathy with children who don’t have basic rights that even children in our school, where 60 percent of students come from lowincome families, take for granted. I wanted them to think critically about consumer spending in the United States and how our gains might be other peoples’ losses. And I hoped that this unit could ultimately inspire them to take action and instill a lifelong interest in such issues.

But could second and third graders understand the complexities and handle the feelings generated by the topic of child labor? I wouldn’t want them to place the blame for the inhumane treatment of children on the children’s parents or on Third World countries. And I hoped they could understand the difference between labor that is a violation of fundamental rights and labor that contributes to a family’s farm or business. Would they see that the abolition of child labor would not end the fundamental problems of unequal distribution of income, that having adults perform the same jobs in inhumane conditions is not an answer? Many adults lack this depth of understanding, so I wasn’t sure how my students would do. But I was soon surprised at how well they grasped aspects of the issue.

Kat planned the first week with a focus on the history of child labor in the United States. Students made a web on labor in general and brainstormed children’s rights, read and discussed the United Nations Children’s Rights document, and learned to differentiate rights from privileges. We had discussed the basic needs of animals previously, and that helped them when we started to discuss human needs and rights. Then the students learned about the history of child labor in the United States. They studied books such as Fire at the Triangle Factory, Danger in the Breaker, and Trouble at the Mines. We read aloud Mother Jones and the March of the Mill Children and Working Children. With this literature, they also gained a basic understanding of labor concepts such as unions, boycotts and strikes.

I began the following week by reading aloud a poem written in Spanish and English about a girl who sells chocolates on the street, “The Girl with Chocolates” or “La niña de los chocolates.” I revealed the poem one stanza at a time, asking students to guess what the poem was about.

A little girl in sandals is walking on the avenue. Her hair, so long and black, shines, and turns deep sea-blue.

She wears a green dress with seven flowers printed on the front and carries a box of chocolates.

After reading the first two stanzas, students were thinking that the poem was about a girl who had bought some chocolates for her mom’s birthday, or maybe that the girl had spent money on chocolates for herself. But as we read on, the students realized that she was working and lacked the basic rights (education and play) that they had agreed all children should have.

At six years old school is her only dream but she must sell her chocolates and care for her brothers and sisters …

Since we had studied child labor in the context of U.S. history, I was curious to hear when the students thought the poem took place. Interestingly, the children whose families had immigrated from Mexico or South America agreed that it takes place now. But the majority of the children were convinced that the poem took place in the past.

After lunch, Kat read the story of Iqbal Masih from Stolen Dreams. The students listened intently to the description of the work of Iqbal and other children in Pakistan who were bonded to owners of carpet factories, destined to work years for three cents a day to pay off their parents’ debts. They learned how these children work for pennies, tying millions of knots in coarse twine in the process of creating carpets that sell for more that $2000 in the United States. The conditions are brutal, as children work as many as 16 hours a day in severe heat and if they protest, as did Iqbal, they are beaten and tied to their chairs. In 1992, Iqbal spoke out at a meeting supporting the proposal of a law that would ban child labor in the carpet factories. He then broke out of his bondage, went to school, and traveled around to support other bonded child laborers and to gain better conditions for workers in carpet factories. When the class learned that Iqbal got shot and killed at age 12, they were shocked.

“I know what happened!” said Rosalie. “He was speaking out against child labor and they just wanted to get back at him.”

“That’s just like Dr. King,” added Tara. “He worked for it to be fair for all people, too, and then he got killed.” Throughout the unit, students made such connections between child labor and struggles against inequity that they had learned about in other contexts. A challenge that I had confronted in teaching about the Civil Rights Movement – to enable students to understand that it was a movement, not one man, that led to change – resurfaced during this unit. Like that of Martin Luther King, Jr., the story of Iqbal overshadowed discussions we had of grassroots efforts to confront the issue of child labor. I didn’t succeed in scheduling a speaker from a campus antisweatshop organization, but I plan to include grassroots organizers when I teach this in the future.

From an Internet site of the International Labor Organization (ILO) (see the resources section of this article), I copied scenarios of children working, some deemed by the ILO as “child labor,” others not. From their knowledge of child labor in the United States and the story of Iqbal, students helped make lists of what did and did not constitute child labor.

For jobs that weren’t classified as child labor, the students agreed that working was a choice, that they would be able to go to school, that they would be saving their money for extra things, and that they would be paid more. For child labor, students listed the following: not a choice, can’t go to school, working for the basic needs of their family, sometimes being hurt, long hours, and low pay.

I read the scenarios from the ILO website and the students categorized them. I had been concerned that students would confuse doing household chores and homework with child labor, but, in fact, they had a very clear idea of the differences between the two. I did, however, want to introduce the concept that not all kids who work do it under the harsh conditions illustrated by the story of Iqbal or the scenarios of brick layers and clothing manufacturers from the ILO site. I showed a segment from the video, Central American Children Speak: Our Lives and Our Dreams, which depicts the life of a Nicaraguan boy who sells bread on the street for his family business. He talks about the pleasures and the struggles of his job. He goes to school part-time and plays stickball with his friends. The class agreed that his situation was different from their definition of “child labor” because he was able to go to school and play, because he enjoyed aspects of his job, and wasn’t physically harmed from it. We also read aloud daily from The Most Beautiful Place, a book that reveals a similar situation in which a Guatemalan boy shines shoes to help meet his family’s basic needs. He teaches himself to read and when his grandmother realizes that he has missed a year of school, he is able to follow his dream of getting an education.

Later in the week, I passed out copies of photos from Stolen Dreams. I suggested students describe not only what they saw in the photo, but also what they imagined the children in the photos felt and what their lives were like. I reminded them to think about children’s rights and how we had defined child labor the day before. I didn’t do any major editing, except for helping students cut out extraneous pronouns and connecting words. If students seemed to be stuck, I prompted them by asking them to describe what they saw and felt. Their poems were remarkable, both in content and form.

Roberto, only a month in the United States, wrote about a photo of a child construction worker in Kathmandu, Nepal.

no trae zapatos

saca tierra de un hoyo

carga cosas pesadas

trabaja entre el calor

trabaja todos los dias

le pagan poco dinero

no juega porque no tiene tiempo

no va a la escuela

no come hasta la noche

no tiene bicicleta

es muy pobre

con el dinero que le dan

no le alcanza para comer

no tiene cama

tiene una casa de adobe

quiere vivir en un pais bien

que tenga para comer . . .She doesn’t wear shoes

removes dirt from a hole

carries heavy things

works in the heat

works every day

they pay her little money

she doesn’t play because there isn’t

time

doesn’t go to school

doesn’t eat until nighttime

doesn’t have a bike

is very poor

the money that she earns

is not enough for food

doesn’t have a bed

has a house made of mud

wants to live in a better country

where there is food to eat . . .

WHERE CLOTHING IS MADE

The next day we examined where our own clothing is made. Most students guessed their shirts were made in the United States “because that’s the closest.” Cassandra said that they must be made in the United States because people in other countries speak different languages and wouldn’t be able to put English words on the shirts. Tara, however, said that most of the things around her house were made in China, so her shirt was probably made there, too. Then several others followed suit by guessing China. Evan, who has politically astute parents, was agonizing over the “right” answer. He tried to turn his shirt around to see the label. Prevented from doing that, he deduced that his shirt must be made in the United States because he got it in a public museum, rather than in a store. I directed students to find partners and read each other’s labels, writing the countries’ names on index cards. One at a time they read their cards, and we found the countries on the map. Although we had a fair share made in the United States (five out of 18), the students were surprised to discover that their shirts were made so far away, most in Asia and others in Central America. Evan’s museum tshirt was made in Honduras. I asked the class why they thought that their shirts were made in countries so far away, instead of in the United States.

“Maybe they make them better there,” someone guessed. “I guess the United States pays them to make them there,” said another student. I told them that I had a video of a factory in Honduras where some shirts like the ones they had on were made, sewn by children 13 to 15 years old.

“What does your big sister do during the day,” I asked MaiSee.

“She goes to school,” she said.

“Well, these girls work in a factory, called a maquila or sweatshop, sewing shirts. As you watch the video, notice if they are getting their basic needs and rights met.”

We then watched part of Zoned for Slavery, a video in which a reporter sneaks into a maquila in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and interviews the girls about their working conditions. The girls are also filmed and interviewed at their homes and on their way to the factory. Although the video is geared for high school students, I found that the images of the girls’ lives in and out of the factory and their own words spoke for themselves. There were a few parts that I skipped because they were not age appropriate, including the ending segment that shows how the girls were given birth control pills disguised as vitamins to prevent pregnancy and thereby increase productivity.

The students groaned as they heard that the girls need to pay for their bus transportation and their lunch out of their meager salary. They paid close attention to translations of the girls’ responses as they related the working conditions in the factory.

After the video, I asked the students to share reactions. As the students spoke, I encouraged their conjectures but did not add much beyond repeating or rephrasing their ideas and encouraging them to explore further.

“That’s not fair,” said Cassandra. “They can’t even go to the bathroom or get a drink of water! I think we need to get all those girls on a plane and bring them here!”

After talking about the impracticality of her suggestion, other students offered ideas.

“We should give money to the poor people so they wouldn’t have to work,” said Juan Pedro.

Rosalie added, “I have an idea. Don’t buy any shirts from those companies. Then they won’t make so much money!” I asked the students if they remembered that that was called a boycott. Several did, mentioning the Montgomery Bus Boycott as an example.

“But we’d have to get thousands and thousands of people to join in,” argued Evan. “That would be hard.” I shared that students on campus had organized a boycott against the Gap to protest child labor and poor working conditions. Sheyna had another idea. “Write a letter to George Bush, saying that child labor is bad.”

Cassandra interjected, “But he doesn’t answer his letters. It’s just a secretary or something who writes all the answers. Remember how we all got the same letter back from him last year?”

She added, “I think that we should make the clothes cost what the workers make – 27 cents – that way the company wouldn’t make any money and they’d have to give the workers more money so that they could make the shirts cost more.”

Tara said, “George Bush could shut down all the companies that use child labor.”

Evan said, “But child labor is already against the law in the United States. We should make it a law that we can’t sell things here that are made by child labor in another country.”

“I know what we should do,” interjected Cassandra, “We should tell the whole school about child labor. We could make fliers telling people to boycott companies who use child labor.”

“And send letters to companies saying that we won’t buy their shirt because they use child labor” added Rosalie.

The momentum of wanting to take action followed into the next days and the following weeks as the students wrote letters to the newspaper, the president’s wife, and companies protesting child labor. I had started off the letterwriting activity as an exercise in persuasive writing, but students chose to write their letters during draft book (free writing) periods and any other available time.

Opinion differed as to who would be the best audience for their letters of protest. I encouraged dialogue but allowed each student to make his or her own decision. Juan Pedro, another immigrant from Mexico, showed more interest in this topic than any other we’ve studied. He became a leader, sharing his knowledge of the lives of working children and his ideas about how the companies benefit from the low-paid workers. He suggested we write to the local newspapers so that we could tell more people our concerns. At least half the class followed his example, many writing their second or third letter.

TYING KNOTS

As students continued to work on editing and typing their letters, we did other activities related to child labor. We did a simulation activity in which students were assigned a task measuring or tying knots in thick twine, supposedly as part of a rug making factory. Kat and I took on the roles of the managers. The students were very serious about doing their tasks within strict guidelines of no talking, no drinks or bathroom breaks, no mistakes, no getting up from their seats. Any breaking of the rules or imperfect product reduced their pay (five pennies). We broke after 15 minutes, concerned that some students were getting upset, but some said, “That was fun. Let’s do it again.” Other students had more serious responses: “That felt real,” said Rosalie. “I’m never going back to that place. I was so tired. My fingers were sore from tying all those knots.”

Cassandra said, “That burned my fingers really hard. And I didn’t like the owners. They were too bossy. It wasn’t my fault that I couldn’t cut the string right.”

Most students complained that they were thirsty (it was a very hot day), sore, and bored.

MaiSee said, “The owners wanted us to do all their work. You had to work fast or else not get your pay. It would be really, really hard if you had to go to the bathroom and you couldn’t go.”

Tara said, “That felt real. It made my paper cuts hurt and my hands hurt real bad.”

Kaya guessed, “I bet you were doing this so we could feel how the workers felt!”

We also used the International Labor Organization website to submit the students’ daily schedules and then compare these with the daily schedules of three child laborers. From that information, students filled in circle graphs which graphically illustrated the differences in their daily lives from those of a cigarette maker, a brick layer, and a clothing factory worker.

“All they get to do is work, sleep and eat!” commented MaiSee. They wrote each activity in terms of fractions of the day and also completed word problems related to their working hours and small salaries.

In the following days, two more students brought in lists of where their clothes were made, including Sheyna, who lets it be known that she hates doing homework.

TV TURN-OFF WEEK

Our child labor unit spilled over into TV Turn-off Week. We examined tricks that advertisers use to convince children to buy their products through a video, Buy Me That!, and discussions of their experiences. Students broke into groups to design and perform roleplays of advertisements for a Nike sweatshirt, Adidas tennis shoes, a Digimon toy made in China, and a Gap t-shirt. After their roleplays of the ads, students told the truth about their product.

Did they understand all the complexities of child labor and all the connections between Third World poverty and corporate gain? No, but they demonstrated through their conversations, written work, and oral presentations that they not only developed empathy for the working children around the world, but also that they were beginning to see where company profit and consumer choices played a part. And I believe the unit had special meaning to my Latino students. Juan Pedro and Roberto, in particular, showed by their level of oral and written participation that the subject was relevant to their experiences. Finally, I saw some of the best writing of the year in the students’ poems and persuasive essays. Not only were they willing to write, but they were also enthusiastic about spending extra time on the computer to produce finished pieces. The enthusiasm, I felt, came from the conviction that the writing was for an important purpose. The students were engaged in an effort to help stem injustice. It could be argued that their impact will be small, but I believe they won’t forget the lessons learned about taking action.

As we finished up the school year, the topic of labor continued to come up. Kat brought in information on Global Exchange’s campaign against the use of child slavery and fair wages for adult workers in cocoa plantations on the Ivory Coast. We discussed the campaign to speak out on the issue by responding to the question of what new color M&M should create by voting for free-trade chocolate. Later that day Tara found an ad in a teen magazine that ironically said, “Want to make a difference? M&M needs you! To vote for your color!”

At the end of the year, a teacher stopped in to talk to the class about her trip to Guatemala. She showed us a picture of young girls boarding a bus.

“Where do you think these girls are going?” she asked. In fact they were not going to school, as we all had guessed, but to work in a clothing factory. She recounted the inhumane treatment they experienced and the lack of basic rights. The class surprised her with their knowledge about sweatshops.

In the midst of our discussion, I noticed that kids were growing restless. I started to reprimand them, then stopped. My students were twisting their t-shirts around to investigate their labels.

*Students names have been changed.

CHILD LABOR BOOKS AND RESOURCES

Anaya, Rudolfo. Elegy on the Death of Cesar Chavez. El Paso, Texas: Cinco Puntas Press, 2000.

Central American Children Speak: Our Lives and Our Dreams. Minneapolis, MN: Resource Center of the Americas, 1993.

A Children’s Chorus: Celebration the 30th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of the Child. New York: UNICEF, 1989.

Colman, Penny. Mother Jones and the March of the Mill Children. Millbrook, CT: Millbrook Press, 1994.

Hoose, Phillip. We Were There, Too! Young People in U.S. History. New York, NY: Melanie Kroupa Books, 2001.

Littlefield, Holly. Fire at the Triangle Factor. Minneapolis, MN: Carolrhoda Books, 1996.

McCully, Emily Arnold. The Bobbin Girl. New York, NY: Dial Books for Young Readers, 1996.

Newman, Shirlee. Child Slavery in Modern Time. New York, NY: Franklin Watts, 2000.

Nye, Naomi Shihab. The Tree Is Older Than You Are: A Bilingual Gathering of Poems and Stories from Mexico with Paintings by Mexican Artists. New York, NY: Aladdin Paperbacks, 1995.

Parker, David with Lee Engfer and Robert Conrow. Stolen Dreams: Portraits of Working Children. Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publications, 1998.

Rappaport, Doreen. Trouble at the Mines. New York, NY: Skylark, 1987.

Saller, Carol. Working Children: Picture the American Past. Minneapolis, MN: Carolrhoda Books, Inc., 1998.

International Labor Organization

www.us.ilo.org/ilokidsnew/