Editorial: Our Billionaire Philanthropist Problem – and Yours

the Editors of Rethinking Schools

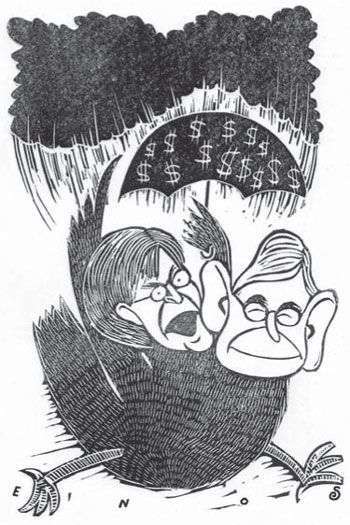

Illustrator: Randall Enos

The one thing that unites billionaire philanthropists Bill Gates and Eli Broad and progressive education activists is the belief that when it comes to public education, none of the presidential candidates from either political party has much to offer. However, that’s as far as it goes.

In April, Gates, the founder and chairman of Microsoft, and Broad, a real estate and insurance mogul and a Democratic party cash cow, announced the formation of Ed in ’08/Strong American Schools, a $60 million multiplatform media campaign to drive education issues higher on the 2008 presidential agenda. Arthur Levine, president emeritus of the Teachers College at Columbia University, hailed it as “the most important philanthropic investment in education in years.”

Apparently, Levine isn’t troubled that while Gates and Broad say they want a “robust” national debate on education, they’ve force-fed us the three solutions to all that ails public education: a standard national curriculum, merit pay for teachers, and more time in the classroom for everyone.

How democratic can a debate be when the answers have already been decided?

The policy people at Ed in ’08 would like us to believe that their phrase “strengthening America’s schools” doesn’t mean standardizing curriculum. Curiously, in one paragraph they say they are against a national curriculum, while in another demand presidential candidates explain how they’re going to work with local and state education leaders to “arrive at rigorous American educational standards.” Is there a difference?

Strong American Schools wants to streamline the national market for textbook publishers who have to cram books “with enough material to cover all 50 state standards – literally too much to learn in one year.” Yet, if you streamline textbooks, standardized tests will have to be similarly aligned. So, no matter how you slice it, we end up with a national curriculum.

Instead of addressing long-standing structural problems in American education – such as segregation, run-down schools, bloated class sizes, and inadequate teacher pay – Ed in ’08 proposes corporate-style teacher merit pay schemes. In particular, the Ed in ’08 policy primer highlights the Milken Family Foundation’s Teacher Advancement Program. Although the primer admits that evaluating teachers’ effectiveness “takes more than just looking at students’ end-of-year test scores,” in the next sentence it poses as an alternative “look[ing] at how much a teacher’s students learn from the beginning of the school year to the end of it,” which in practice means increased amounts of and emphasis on standardized testing.

Their two-page “fact sheet” is equally revealing, suggesting that a key way to get “effective teachers” is to “measure teachers’ performance in the classroom, and pay them more if they produce superior results.” Sounds like a significant reliance on testing to us. And if No Child Left Behind didn’t sufficiently peg curriculum to tests, then merit pay puts this whole process on steroids.

Strong American Schools says that “learning takes time and it takes support.” Instead of rebuilding dilapidated schools and lowering class sizes, Strong American Schools demands that children spend more days in school. For the Gates-Broad collaborative, evidently more is better.

“Support” is a weasel word du jour. If one teases out its meaning from Strong American Schools’ material, we can see that the schools of tomorrow will offer teachers not more support, but more supervision. “Time audits” and “expert advice” will allow administrators to run schools more “efficiently.”

The Ed in ’08 campaign calls for longer school days and years, and stresses doing so would increase time for classes such as art, drama, and music – “activities that build confidence, challenge young minds, and teach skills beyond the academic curriculum.”

This all sounds good, but it would require huge increases in school funding the campaign doesn’t address. It also runs against the grain of current trends toward standardized, test-driven narrowing of school curricula; the imposition of scripted, prepackaged curricula; and the adoption of top-down corporate models of school administration.

Even Strong American Schools’ “sky is falling” rhetoric is dated – we heard the same thing when the Reagan administration dumped the now largely discredited “Nation at Risk” onto an anxious and largely uninformed public.

A revolution in American education isn’t going to come from two billionaires who’ve lived off a profoundly flawed global economic system that creates great class chasms and unnecessary cultural strife. No, a revolution in American education will have to come from all the rest of us – the grassroots.