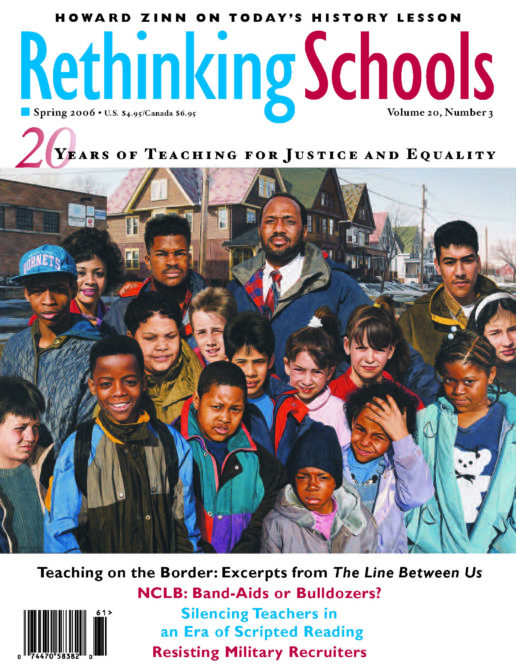

Editorial: It Was 20 Years Ago Today

1986: Ronald Reagan president, Rethinking Schools born.

Three years earlier, the U.S. Department of Education’s National Commission on Excellence in Education had announced that we were “a nation at risk,” suffering from “a rising tide of mediocrity,” committing an act of “unilateral educational disarmament.”

For 20 years, in our quarterly publication and in our books, Rethinking Schools has described children at risk, classrooms at risk, schools at risk, communities at risk, our society at risk. But Rethinking Schools has sought to articulate fundamentally different causes of — and responses to — those risks.

1986 was early in the standards and testing mania that led eventually to the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation. Rethinking Schools has grown up in an age when U.S. corporate and government elites imply that the problem with schools lies in large part with teachers who aren’t doing their jobs. Equity and quality can be achieved, we’ve been told, with “high standards” when teachers are adequately “trained” to teach to those standards. And standards demand constant measurement — whose results, accordingly, should lead to “accountability” and consequences.

Although these policies and practices have been implemented differently from state to state and community to community, over the last 20 years, U.S. policymakers have settled on this consensus: Offer rhetoric in place of resources, blame economic and social crises on the schools, increasingly treat education as simply another business, and look to marketplace metaphors and practices to shape school reform. Rethinking Schools has grown up amid campaigns for school vouchers, education management organizations (EMOs), and creeping privatization of more and more educational services, from tutoring and custodial work to teaching and administering schools.

This educational commodification has not occurred in a vacuum, but rather in the context of what has come to be known as globalization. Over these last 20 years, throughout the world, U.S. leaders have touted “free market” solutions at every opportunity. Poor countries have been urged, sometimes forced, to sell off public institutions, cut subsidies to the poor, remove restrictions on foreign investment, and open their markets to cheap imports from the so-called developed world. These policy prescriptions — referred to as neoliberalism throughout the Third World — have been good for banks and corporations, and just about no one else. Neoliberalism encourages profit-directed private choice supported by government action, and its logic has seeped into school reform initiatives of the past 20 years — here and around the world.

Origins and Mission

We launched Rethinking Schools in this chilly social climate. Initially, we had no aspirations to be a national journal. In fact, “modest beginnings” barely captures our shoestring origins: Our first issue was laid out on a kitchen table with rubber cement. We hoped to be a forum for Milwaukee-area teachers and education activists to offer alternative perspectives on what we saw as the often wrongheaded and top-down policies of Milwaukee public schools. But as we analyzed racial and class inequities in Milwaukee schools and proposed solutions, we began to reach a national audience.

Since these early days, Rethinking Schools has consistently pressed for a defense of public education, but also for its radical revision. We’ve tried to demonstrate through story and concrete example how schools can be more just, more lively, more visionary — alert to complementary missions of educating students to be successful in today’s world as we equip them with the critical skills to analyze and transform it.

Twenty years ago we also couldn’t have imagined we’d become a book publisher. By 1991 we had published a number of articles on the racial biases embedded in the Columbus-discovered-America myth and how students could learn critical literacy skills as they considered the contact between Europeans and indigenous peoples. For the Columbus quincentenary, we published Rethinking Columbus; it subsequently sold more than a quarter of a million copies. We realized that teachers and teacher educators were eager for materials that offered examples of critical teaching for social justice.

In 1994 we followed with a collection of our best classroom-based articles, Rethinking Our Classrooms. By this time, the academic literature was beginning to fill up with books that argued for a “critical pedagogy” and a “language of possibility,” but few of these offered real-world examples of this kind of teaching. In Rethinking Our Classrooms we advocated a classroom practice that is critical, multicultural, anti-racist, pro-justice, participatory, playful, hopeful, culturally sensitive, and academically rigorous — a tall order, but we sought to give readers examples of this kind of teaching at different grade levels and in multiple disciplines.

These two classroom-based books were followed by a number of books, including: Rethinking Our Classrooms; Reading, Writing, and Rising Up: Teaching About Social Justice and the Power of the Written Word; Rethinking Globalization: Teaching for Justice in an Unjust World; The New Teacher Book; Rethinking Mathematics; Whose Wars? Teaching About the Iraq War and the War on Terrorism; and most recently, The Line Between Us: Teaching About the Border and Mexican Immigration. In our magazine and books, we’ve aimed to nurture a grassroots literature of teaching practice that highlights ways teachers can blend meaningful academic standards with teaching for equality and justice. And in our books Rethinking Schools: An Agenda for Change (1995) and Rethinking School Reform (2003), we offered examples of the intersection of classroom, school, district, and social reform.

It’s discouraging that at such a dangerous moment in world history, U.S. teachers are being bullied into teaching increasingly narrow curricula and drilling students for insipid standardized tests. Now, more than ever, Rethinking Schools sees our mission as offering both encouragement and resources for teachers who want to equip their students to think deeply about society — especially issues of race, class, and our connections to others around the world. We show how teachers can weave social and ecological concerns into all aspects of the curriculum.

We seek to tell stories that highlight exemplary teaching practices and feature teachers who resist top-down mandates and who fight for their right to teach about things that matter and to be more than test-taking coaches.

Educators as Activists

From our beginning, Rethinking Schools has insisted that classroom life needs to be at the core of any conversation about improving education. But we’ve also argued that in order to protect and nurture academically rigorous social justice teaching, educators need to see themselves as activists beyond the classroom — and in alliance with parents and other groups. Our first publication after Rethinking Columbus was False Choices: Why School Vouchers Threaten Our Children’s Future. Five years later we updated and expanded it to become Selling Out Our Schools: Vouchers, Markets and the Future of Public Education. Although most voucher schemes have been defeated at the polls, the market-as-salvation ideology has never been stronger, and Rethinking Schools continues to urge readers to defend public schools — indeed, the very idea of the public good — as we urge their transformation. Our 1997 booklet, Funding for Justice, demystified school finance issues and offered tools for educators and activists to organize for adequate and equitable public school funding.

Too often teachers of conscience have regarded teacher unions as unpleasant necessities, vehicles for protecting wages and working conditions and curbing the worst administrator abuses, yet having little to do with the quality of education itself. But teacher unions are institutions that are the public face of teachers in communities as well as at the national level through the National Education Association and the American Federation of Teachers. In 1999, we published Transforming Teacher Unions: Fighting for Better Schools and Social Justice to promote a more affirmative vision of teacher unions as organizations that can best defend teachers when they adopt a larger social justice mission and also address curricular issues.

Rethinking Schools is a publishing project, but our aspirations link us to activism. Rethinking Schools editors were instrumental in launching the National Coalition of Education Activists in 1988, have served in the leadership of local teacher unions, and have initiated local teacher social justice groups. Recently, we’ve been encouraged by the growth of activist groups around the country that connect teachers, student teachers, teacher educators, parents, and community members concerned with making schools more vital and socially responsive. As we begin our next 20 years, we will continue to write about and support these initiatives.

Challenges Ahead

We remain hopeful, but aware of the challenges ahead. It’s hard to remember a time that felt this grim. The United States continues its illegal and immoral war against Iraq. The Bush administration responds to any global obstacle with military might and repression; this regime seems locked into an endless loop of spying and lying. The United States remains committed to unsustainable economic practices, and corporations continue to tell us that happiness is just one purchase away. Our leaders push “free trade” on poor countries and then demonize those immigrants who flee the resulting economic devastation. The ecological threats posed by a system of production-for-profit and hyper-consumption are often glossed over, but there are indications that the long-term effects of climate change alone will be permanent and disastrous.

Hurricane Katrina exposed stunning manifestations of racism and economic inequality in our society. Vast educational disparities throughout the United States represent ongoing, silent Katrinas, crippling opportunity in poor communities day in and day out. These are “cheap children,” as Jonathan Kozol scolds. And the Bush mantra is still: “Let them eat tests.” Our leaders — Democrat and Republican alike — spend huge sums on tanks, Humvees, and other tools of war, but schools are crumbling and class sizes are swelling for lack of support. NCLB packages some of the worst trends of top-down, test-driven reform under a veneer of concern for children and schools.

For those inside schools, NCLB’s culture of testing has produced more insecurity, more teaching to the test, more “teacher proof” curricula, more panicky administration regulations. With its emphasis on narrow, testable skills, NCLB is choking out multicultural, anti-racist curriculum as well as art, physical education, foreign language instruction, and even recess.

So where’s the hope? We have to go back to the end of Nixon’s reign, well before the birth of Rethinking Schools, to remember an administration with so little credibility and held in such widespread contempt; yet this regime’s illegitimacy is pregnant with activist potential, and popular defiance is beginning to emerge in diverse spheres. While the Bush crowd is consumed with Iraq, Afghanistan, and Iran, popular movements have blossomed throughout Latin America, rejecting the “Washing-ton consensus” of free-market reforms. People are denouncing a soulless model of development and are discussing alternatives with an intensity not seen in decades. In the United States, Cindy Sheehan’s courageous denunciation of war, California teachers’ refusal to teach a mindless cat-hat-sat reading program, and a U.S. district judge’s acid rejection of creationism masquerading as science in Dover, Penn., all illustrate a growing resistance.

We especially draw hope from our students. From the little explosions of “aha” during a writing activity, a discussion, an experiment, or a role play to moments when our students exhibit fairness and human decency, we can’t help but feel hopeful and joyful in their company. Working with young people underscores the urgency of the work we do, the necessity of having confidence in a much better future. Teaching demands hope.

In his latest book, The Impossible Will Take a Little While, Paul Rogat Loeb writes that history “shows that even seemingly miraculous advances are in fact the result of many people taking small steps together over a long period of time.” For the past 20 years, in these pages, teachers, teacher educators, community organizers, students, and journalists have been rethinking schools and society. We’ve been taking small steps together. Each issue of the magazine and every book we publish is a gesture of hope, of our conviction that together we can change the world.

Twenty years and still walking.