Ebonics and Culturally Responsive Instruction

What Should Teachers Do?

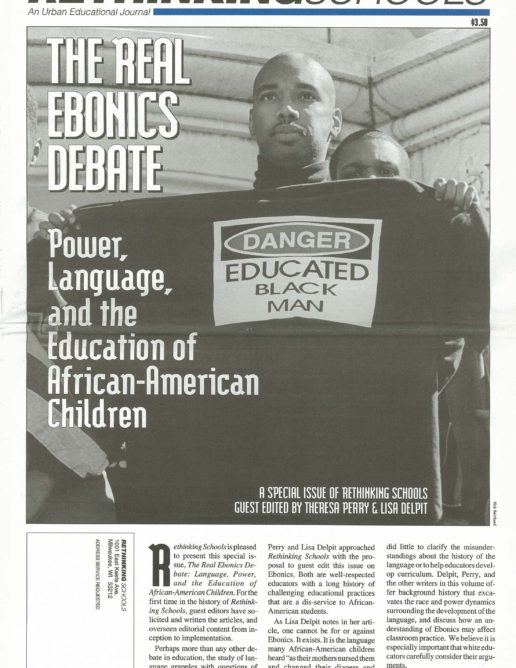

The “Ebonics Debate” has created much more heat than light for most of the country. For teachers trying to determine what implications there might be for classroom practice, enlightenment has been a completely non-existent commodity. I have been asked often enough recently, “What do you think about Ebonics? Are you for it or against it?” My answer must be neither. I can be neither for Ebonics or against Ebonics any more than I can be for or against air. It exists. It is the language spoken by many of our African-American children. It is the language they heard as their mothers nursed them and changed their diapers and played peek-a-boo with them. It is the language through which they first encountered love, nurturance and joy.

On the other hand, most teachers of those African-American children who have been least well-served by educational systems believe that their students’ life chances will be further hampered if they do not learn Standard English. In the stratified society in which we live, they are absolutely correct. While having access to the politically mandated language form will not, by any means, guarantee economic success (witness the growing numbers of unemployed African Americans holding doctorates), not having access will almost certainly guarantee failure.

So what must teachers do? Should they spend their time relentlessly “correcting” their Ebonics-speaking children’s language so that it might conform to what we have learned to refer to as Standard English? Despite good intentions, constant correction seldom has the desired effect. Such correction increases cognitive monitoring of speech, thereby making talking difficult. To illustrate, I have frequently taught a relatively simple new “dialect” to classes of preservice teachers. In this dialect, the phonetic element “iz” is added after the first consonant or consonant cluster in each syllable of a word. (Maybe becomes miz-ay-biz-ee and apple, iz-ap-piz-le.) After a bit of drill and practice, the students are asked to tell a partner in “iz” language why they decided to become teachers. Most only haltingly attempt a few words before lapsing into either silence or into Standard English. During a follow-up discussion, all students invariably speak of the impossibility of attempting to apply rules while trying to formulate and express a thought. Forcing speakers to monitor their language typically produces silence.

Correction may also affect students’ attitudes toward their teachers. In a recent research project, middle-school, inner-city students were interviewed about their attitudes toward their teachers and school. One young woman complained bitterly, “Mrs. ___ always be interrupting to make you ‘talk correct’ and stuff. She be butting into your conversations when you not even talking to her! She need to mind her own business.” Clearly this student will be unlikely to either follow the teacher’s directives or to want to imitate her speech style.

Group Identity

Issues of group identity may also affect students’ oral production of a different dialect. Researcher Sharon Nelson-Barber, in a study of phonologic aspects of Pima Indian language, found that, in grades 1-3, the children’s English most approximated the standard dialect of their teachers. But surprisingly, by fourth grade, when one might assume growing competence in standard forms, their language moved significantly toward the local dialect. These fourth graders had the competence to express themselves in a more standard form, but chose, consciously or unconsciously, to use the language of those in their local environments. The researcher believes that, by ages 8-9, these children became aware of their group membership and its importance to their well-being, and this realization was reflected in their language.1 They may also have become increasingly aware of the schools’s negative attitude toward their community and found it necessary — through choice of linguistic form — to decide with which camp to identify.

What should teachers do about helping students acquire an additional oral form? First, they should recognize that the linguistic form a student brings to school is intimately connected with loved ones, community, and personal identity. To suggest that this form is “wrong” or, even worse, ignorant, is to suggest that something is wrong with the student and his or her family. To denigrate your language is, then, in African-American terms, to “talk about your mama.” Anyone who knows anything about African-American culture knows the consequences of that speech act!

On the other hand, it is equally important to understand that students who do not have access to the politically popular dialect form in this country, are less likely to succeed economically than their peers who do. How can both realities be embraced in classroom instruction?

It is possible and desirable to make the actual study of language diversity a part of the curriculum for all students. For younger children, discussions about the differences in the ways television characters from different cultural groups speak can provide a starting point. A collection of the many children’s books written in the dialects of various cultural groups can also provide a wonderful basis for learning about linguistic diversity,2 as can audio taped stories narrated by individuals from different cultures, including taping books read by members of the children’s home communities. Mrs. Pat, a teacher chronicled by Stanford University researcher Shirley Brice Heath, had her students become language “detectives,” interviewing a variety of individuals and listening to the radio and television to discover the differences and similarities in the ways people talked.3 Children can learn that there are many ways of saying the same thing, and that certain contexts suggest particular kinds of linguistic performances.

Some teachers have groups of students create bilingual dictionaries of their own language form and Standard English. Both the students and the teacher become engaged in identifying terms and deciding upon the best translations. This can be done as generational dictionaries, too, given the proliferation of “youth culture” terms growing out of the Ebonics-influenced tendency for the continual regeneration of vocabulary. Contrastive grammatical structures can be studied similarly, but, of course, as the Oakland policy suggests, teachers must be aware of the grammatical structure of Ebonics before they can launch into this complex study.

Other teachers have had students become involved with standard forms through various kinds of role-play. For example, memorizing parts for drama productions will allow students to practice and “get the feel” of speaking standard English while not under the threat of correction. A master teacher of African-American children in Oakland, Carrie Secret, uses this technique and extends it so that students video their practice performances and self-critique them as to the appropriate use of standard English (see the article “Embracing Ebonics and Teaching Standard English”). (But I must add that Carrie’s use of drama and oration goes much beyond acquiring Standard English. She inspires pride and community connections which are truly wondrous to behold.) The use of self-critique of recorded forms may prove even more useful than I initially realized. California State University-Hayward professor Etta Hollins has reported that just by leaving a tape recorder on during an informal class period and playing it back with no comment, students began to code-switch — moving between Standard English and Ebonics — more effectively. It appears that they may have not realized which language form they were using until they heard themselves speak on tape.

Young students can create puppet shows or role-play cartoon characters — many “superheroes” speak almost hypercorrect standard English! Playing a role eliminates the possibility of implying that the child’s language is inadequate and suggests, instead, that different language forms are appropriate in different contexts. Some other teachers in New York City have had their students produce a news show every day for the rest of the school. The students take on the personae of famous newscasters, keeping in character as they develop and read their news reports. Discussions ensue about whether Tom Brokaw would have said it that way, again taking the focus off the child’s speech.

Although most educators think of Black Language as primarily differing in grammar and syntax, there are other differences in oral language of which teachers should be aware in a multicultural context, particularly in discourse style and language use. Harvard University researcher Sarah Michaels and other researchers identified differences in children’s narratives at “sharing time.”4 They found that there was a tendency among young white children to tell “topic-centered” narratives–stories focused on one event–and a tendency among Black youngsters, especially girls, to tell “episodic” narratives–stories that include shifting scenes and are typically longer. While these differences are interesting in themselves, what is of greater significance is adults’ responses to the differences. C.B. Cazden reports on a subsequent project in which a white adult was taped reading the oral narratives of black and white first graders, with all syntax dialectal markers removed.5 Adults were asked to listen to the stories and comment about the children’s likelihood of success in school. The researchers were surprised by the differential responses given by Black and white adults.

Varying reactions

In responding to the retelling of a Black child’s story, the white adults were uniformly negative, making such comments as “terrible story, incoherent” and “[n]ot a story at all in the sense of describing something that happened.” Asked to judge this child’s academic competence, all of the white adults rated her below the children who told “topic-centered” stories. Most of these adults also predicted difficulties for this child’s future school career, such as, “This child might have trouble reading,” that she exhibited “language problems that affect school achievement,” and that “family problems” or “emotional problems” might hamper her academic progress.

The black adults had very different reactions. They found this child’s story “well formed, easy to understand, and interesting, with lots of detail and description.” Even though all five of these adults mentioned the “shifts” and “associations” or “nonlinear” quality of the story, they did not find these features distracting. Three of the black adults selected the story as the best of the five they had heard, and all but one judged the child as exceptionally bright, highly verbal, and successful in school.6

This is not a story about racism, but one about cultural familiarity. However, when differences in narrative style produce differences in interpretation of competence, the pedagogical implications are evident. If children who produce stories based in differing discourse styles are expected to have trouble reading, and viewed as having language, family, or emotional problems, as was the case with the informants quoted by Cazden, they are unlikely to be viewed as ready for the same challenging instruction awarded students whose language patterns more closely parallel the teacher’s.

Most teachers are particularly concerned about how speaking Ebonics might affect learning to read. There is little evidence that speaking another mutually intelligible language form, per se, negatively affects one’s ability to learn to read.7 For commonsensical proof, one need only reflect on nonstandard English-speaking Africans who, though enslaved, not only taught themselves to read English, but did so under threat of severe punishment or death. But children who speak Ebonics do have a more difficult time becoming proficient readers. Why? In part, appropriate instructional methodologies are frequently not adopted. There is ample evidence that children who do not come to school with knowledge about letters, sounds, and symbols need to experience some explicit instruction in these areas in order to become independent readers (See Mary Rhodes Hoover’s article in this issue of Rethinking Schools, page 17). Another explanation is that, where teachers’ assessments of competence are influenced by the language children speak, teachers may develop low expectations for certain students and subsequently teach them less.8 A third explanation rests in teachers’ confusing the teaching of reading with the teaching of a new language form.

Reading researcher Patricia Cunningham found that teachers across the United States were more likely to correct reading miscues that were “dialect” related (“Here go a table” for “Here is a table”) than those that were “nondialect” related (“Here is a dog” for “There is a dog”).9 Seventy-eight percent of the former types of miscues were corrected, compared with only 27% of the latter. He concludes that the teachers were acting out of ignorance, not realizing that “here go” and “here is” represent the same meaning in some Black children’s language.

In my observations of many classrooms, however, I have come to conclude that even when teachers recognize the similarity of meaning, they are likely to correct Ebonics-related miscues. Consider a typical example:

Text: Yesterday I washed my brother’s clothes.

Student’s Rendition: Yesterday I wash my bruvver close.

The subsequent exchange between student and teacher sounds something like this:

T: Wait, let’s go back. What’s that word again? {Points at “washed.”}

S: Wash.

T: No. Look at it again. What letters do you see at the end? You see “e-d.” Do you remember what we say when we see those letters on the end of the word?

S: “ed”

T: OK, but in this case we say washed. Can you say that?

S: Washed.

T: Good. Now read it again.

S: Yesterday I washed my bruvver…

T: Wait a minute, what’s that word again? {Points to “brother.”}

S: Bruvver.

T: No. Look at these letters in the middle. {Points to “brother.”} Remember to read what you see. Do you remember how we say that sound? Put your tongue between your teeth and say “th”…

The lesson continues in such a fashion, the teacher proceeding to correct the student’s Ebonics-influenced pronunciations and grammar while ignoring that fact that the student had to have comprehended the sentence in order to translate it into her own language. Such instruction occurs daily and blocks reading development in a number of ways. First, because children become better readers by having the opportunity to read, the overcorrection exhibited in this lesson means that this child will be less likely to become a fluent reader than other children that are not interrupted so consistently. Second, a complete focus on code and pronunciation blocks children’s understanding that reading is essentially a meaning-making process. This child, who understands the text, is led to believe that she is doing something wrong. She is encouraged to think of reading not as something you do to get a message, but something you pronounce. Third, constant corrections by the teacher are likely to cause this student and others like her to resist reading and to resent the teacher.

Language researcher Robert Berdan reports that, after observing the kind of teaching routine described above in a number of settings, he incorporated the teacher behaviors into a reading instruction exercise that he used with students in a college class.10 He put together sundry rules from a number of American social and regional dialects to create what he called the “language of Atlantis.” Students were then called upon to read aloud in this dialect they did not know. When they made errors he interrupted them, using some of the same statements/comments he had heard elementary school teachers routinely make to their students. He concludes:

The results were rather shocking. By the time these Ph.D Candidates in English or linguistics had read 10-20 words, I could make them sound totally illiterate . … The first thing that goes is sentence intonation: they sound like they are reading a list from the telephone book. Comment on their pronunciation a bit more, and they begin to subvocalize, rehearsing pronunciations for themselves before they dare to say them out loud. They begin to guess at pronunciations . … They switch letters around for no reason. They stumble; they repeat. In short, when I attack them for their failure to conform to my demands for Atlantis English pronunciations, they sound very much like the worst of the second graders in any of the classrooms I have observed.

They also begin to fidget. They wad up their papers, bite their fingernails, whisper, and some finally refuse to continue. They do all the things that children do while they are busily failing to learn to read.

The moral of this story is not to confuse learning a new language form with reading comprehension. To do so will only confuse the child, leading her away from those intuitive understandings about language that will promote reading development, and toward a school career of resistance and a lifetime of avoiding reading.

Unlike unplanned oral language or public reading, writing lends itself to editing. While conversational talk is spontaneous and must be responsive to an immediate context, writing is a mediated process which may be written and rewritten any number of times before being introduced to public scrutiny. Consequently, writing is more amenable to rule application — one may first write freely to get one’s thoughts down, and then edit to hone the message and apply specific spelling, syntactical, or punctuation rules. My college students who had such difficulty talking in the “iz” dialect, found writing it, with the rules displayed before them, a relatively easy task.

To conclude, the teacher’s job is to provide access to the national “standard” as well as to understand the language the children speak sufficiently to celebrate its beauty. The verbal adroitness, the cogent and quick wit, the brilliant use of metaphor, the facility in rhythm and rhyme, evident in the language of Jesse Jackson, Whoopi Goldberg, Toni Morrison, Henry Louis Gates, Tupac Shakur, and Maya Angelou, as well as in that of many inner-city Black students, may all be drawn upon to facilitate school learning. The teacher must know how to effectively teach reading and writing to students whose culture and language differ from that of the school, and must understand how and why students decide to add another language form to their repertoire. All we can do is provide students with access to additional language forms. Inevitably, each speaker will make his or her own decision about what to say in any context.

But I must end with a caveat that we keep in mind a simple truth: Despite our necessary efforts to provide access to standard English, such access will not make any of our students more intelligent. It will not teach them math or science or geography — or, for that matter, compassion, courage, or responsibility. Let us not become so overly concerned with the language form that we ignore academic and moral content. Access to the standard language may be necessary, but it is definitely not sufficient to produce intelligent, competent caretakers of the future.

©1997 Lisa Delpit

Footnotes

1. S. Nelson-Barber, “Phonologic Variations of Pima English,” in R. St. Clair and W. Leap, (Eds.), Language Renewal Among American Indian Tribes: Issues, Problems and Prospects (Rosslyn, VA: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education, 1982).

2. Some of these books include Lucille Clifton, All Us Come ‘Cross the Water (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1973); Paul Green (aided by Abbe Abbott), I Am Eskimo — Aknik My Name (Juneau, AK: Alaska Northwest Publishing, 1959); Howard Jacobs and Jim Rice, Once upon a Bayou (New Orleans, LA.: Phideaux Publications, 1983); Tim Elder, Santa’s Cajun Christmas Adventure (Baton Rouge, LA: Little Cajun Books, 1981); and a series of biographies produced by Yukon-Koyukkuk School District of Alaska and published by Hancock House Publishers in North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

3. Shirley Brice Heath, Ways with Words (Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge University Press, 1983).

4. S. Michaels and C.B. Cazden, “Teacher-Child Collaboration on Oral Preparation for Literacy,” in B. Schieffer (Ed.), Acquisition of Literacy: Ethnographic Perspectives (Norwood, NJ: Ablex, 1986).

5. C.B. Cazden, Classroom Discourse (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1988).

6. Ibid.

7. R. Sims, “Dialect and Reading: Toward Redefining the Issues,” in J. Langer and M.T. Smith-Burke (Eds.), Reader Meets Author/Bridging the Gap (Newark, DE: International Reading Asssociation, 1982).

8. Ibid.

9. Patricia M. Cunningham, “Teachers’ Correction Responses to Black-Dialect Miscues Which Are Nonmeaning-Changing,” Reading Research Quarterly 12 (1976-77).

10. Robert Berdan, “Knowledge into Practice: Delivering Research to Teachers,” in M.F. Whiteman (Ed.), Reactions to Ann Arbor: Vernacular Black English and Education (Arlington, VA: Center for Applied Linguistics, 1980).