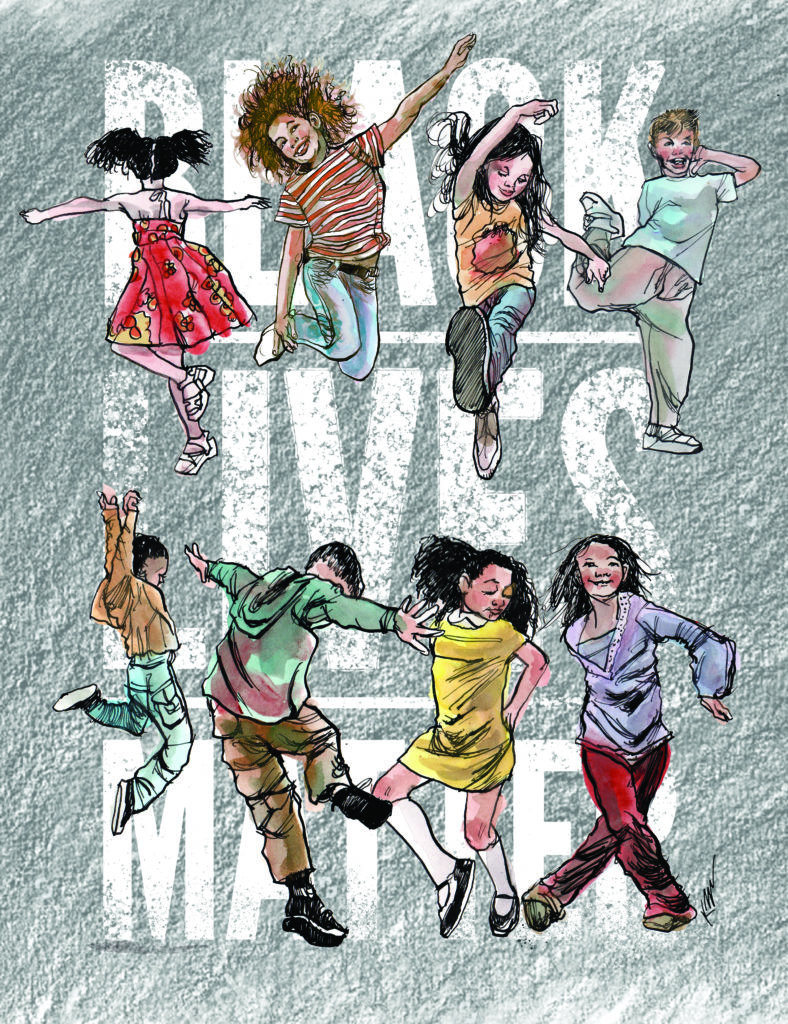

Choreographing for Justice

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

It was May 2020. My elementary dance students logged into our Zoom sessions, class after class. George Floyd

had just been murdered by police officers in Minneapolis, and because we were all home during the COVID-19 lockdown, some of my students were witnessing endless replays on their home screens. I knew I needed to scrap my lesson plan for the day and allow my students to talk about what they had seen and how they felt.

I was honest with my 5th-grade students and told them that I was struggling with the current events we were witnessing. I asked if anyone would like to share their thoughts or feelings about COVID-19, George Floyd, or anything else on their minds.

I was honest with my 5th-grade students and told them that I was struggling with the current events we were witnessing.

Rennie said, “It’s messed up, you know? Like, he kept saying ‘I can’t breathe’ and those cops ignored him.”

Shawn added, “He was yelling for his mom. How come that cop didn’t get off his neck?”

My students were sad and many of them didn’t understand why the cops behaved the way they did.

Diva asked, “Aren’t police supposed to protect us? This doesn’t make sense.”

Some students, however, were not surprised. “My mom and dad always told me that if a cop stops me to put my hands up right away so they can see I don’t have a weapon,” Owen said.

Period after period, grade after grade, my students shared their awareness of racism in their lives. They found commonalities and had open, honest conversations about their own racialized experiences. I tried to end each class by asking “How will we make a change? What will we do to make this better?”

By the next week, protesters were marching outside of some students’ homes. We could see them passing by during our Zoom calls. Many students had TVs on in the background and the whole class could see snippets of masked protests happening country- and world-wide. I decided I needed to give them an outlet and use our shared craft — dance — to support their processing and understanding of these events. As we finished the end of that school year in lockdown, I tried to allow my students the freedom to share their thoughts and feelings, whether or not they shared them through dance.

The elementary school in which I teach is a majority low-income school, but gentrification is changing our neighborhood. My students are around 80 percent Latinx; the remaining 20 percent is a mix of South Asian, Asian, white, and Black. Our school, however, has a teacher population that is mostly white — myself included — and often uncomfortable discussing issues like race and protests with our students.

As a dance teacher, I teach every child in the school, pre–K through 5th grade. Although I spend only one period a week with many of these children, being their teacher year after year brings a different type of closeness, familiarity, and trust.

By the end of the school year in 2020, I knew I wanted to do more to make social justice a stronger part of our dance curriculum, supporting my students in becoming choreographers who use their platforms to challenge social, cultural, and economic inequities to make the world a better place.

By the end of the school year in 2020, I knew I wanted to do more to make social justice a stronger part of our dance curriculum, supporting my students in becoming choreographers who use their platforms to challenge social, cultural, and economic inequities to make the world a better place. After attending a summer webinar about the Black Lives Matter at School movement, I applied for a study group grant to take this journey along with some of my fellow educators. We were accepted and began our staff book club reading Teaching for Black Lives.

As 2021 approached, I invited teachers and parents to join me in an ad hoc committee to plan our first recognition of the Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action. We brought together a week with classroom visitors, virtual assemblies, special projects, movie and music nights, and more. Some of us wore Black Lives Matter shirts and face masks our students had designed with help from the art teacher.

I also began teaching a unit I had created based on the Black Lives Matter at School (BLMAS) principles as retold by Laleña Garcia in What We Believe: A Black Lives Matter Principles Activity Book (Lee & Low Books, 2020). The lessons revolve around sharing various picture books to help children understand and embody the essence of the different BLMAS principles, then adding dance-making skills to create choreographic expressions of them. For example, in the lesson that follows, 2nd-grade students and I explored the BLMAS principle of diversity, first through literature, then through dance.

Naming Differences and Commonalities

In March 2021, a few months after the Week of Action, my 2nd-grade students entered our in-person dance space. After our sharing circle, I asked, “Who can tell me what ‘Black Lives Matter’ means or your feelings about hearing that phrase?”

Sanford said, “It means everyone should be treated fairly.”

Connor added, “And Black people don’t want to have to keep saying that we are important, too.”

I reminded them that we were still exploring BLMAS principles: “We are going to continue learning about principles of the Black Lives Matter at School movement and expressing our thoughts and feelings about them through dance.”

For several weeks, we had created dances based on BLMAS principles. We read aloud books to illuminate BLMAS principles, then students created choreographic projects to express their feelings, thoughts, and understandings through movement. As we worked with a principle, we generated movements and choreographic elements like traveling and in-place movements, body shapes and sizes, levels, relationships, movement qualities, and directions. By the end of a class session, students had created a short dance with a BLMAS principle focus, considering how they could use spacing, timing, and their bodies to most clearly express themselves to the audience.

“What are some BLMAS principles we have worked on so far?” I asked.

Students called out answers: “Black families! Restorative justice! Empathy! Intergenerational!”

“Great remembering! We’ve also made dances exploring collective value, loving engagement, queer and transgender-affirming, and unapologetically Black,” I added.

“Today we will work with the principle of diversity,” I said. In What We Believe, Garcia describes diversity as the “many ways we are different,” and adds “It’s important that we have many different types of people in our community and that everyone feels safe. When that happens, our community shows its diversity.” On the BLMAS website the principle is stated as, “Acknowledging, respecting, and celebrating difference(s) and commonalities.”

To begin, I asked “What is diversity?”

Nolan said, “It means we are all different.”

Theo said, “My family has diversity because we have different cultures. I’m partly Chinese and partly African American and partly other things, too.” Other students nodded in agreement. We had several kids in class who are multiracial and/or come from multicultural backgrounds.

I asked, “Do we think diversity is a good thing? Why?”

Hands shot up. “Of course it’s a good thing!” Serena almost yelled. “My family wouldn’t live here if there was no diversity! I wouldn’t have friends who are different from me if there was no diversity!”

Collectively, we agreed that diversity is good and important and something to celebrate. After all, no two of us are ever the same. I added, “Sometimes people get treated unequally and unfairly because of differences, and that can be harmful; we can call that inequality or inequity. What do we think about that?”

“We all live here together but we are all different and that’s diversity,” Sanford offered. “But people being treated unfairly because they’re different? That’s not good at all.”

Next, we read The Day You Begin by Jacqueline Woodson, an award-winning author who has written many children’s books exploring race and identity. I chose this book because it introduces children in a class who feel alone and different at first, but begin to find connections with one another by sharing their own stories and building empathy.

As I read aloud, students shared their commonalities with the characters in the book.

As I read aloud, students shared their commonalities with the characters in the book. When we met Rigoberto in the book, Jorge shared, “People always say my name wrong and my mom only speaks Spanish and I wish people would ask because I want them to say my name like my mom does.” We talked for a bit about how it feels when someone mispronounces our names and we agreed to make more effort to say names correctly.

When we reached the part of the book when a child feels bad about the lunch her mom packed — kimchi and meat with rice — we stopped and talked about the different kinds of rice we eat with our families, including basmati rice, rice and beans, arroz con pollo, and sometimes rice with every meal.

I asked, “What does rice have to do with diversity?”

Jane continued, “We all eat rice but we all eat different kinds of rice and that is a type of . . . food diversity, I guess?” I heard some giggles, but we agreed that we liked her term: food diversity.

We lingered once more over a part in the story when a classmate is unwelcome in team sports and feels alone; we glimpsed the same child flourishing and happy while holding a book. Maggie said, “I really like to play soccer, but I know some kids don’t and that’s OK with me.”

Raya added, “I used to feel bad because that happened to me — no one wanted me on the team.” Raya explained that the PE teacher helped and she doesn’t feel bad anymore, but she really prefers time in art class anyway.

Shelly said, “So we like to do different things and we are good at different stuff — and that is diversity, too!”

Then I asked my students to put on their choreographer caps. “We’ve read this story and now we have more of an understanding of what diversity is, how we include everyone even though we have different backgrounds, genders, skin colors, beliefs, and more. We know why diversity is important — so we can respect and celebrate the differences in all of us. How can we explore this Black Lives Matter at School principle through dance?”

Choreographing Diversity

Because I didn’t want students to just pantomime or “act out” the story, I offered the idea of concentrating on movement qualities, which means how we are moving. I asked, “How can we walk in different ways?”

Celia said, “We can walk in a stiff way like when we were scarecrows in kindergarten, or in a floppy way like when we pretended to take all of our sticks out.”

“Exactly!” I said.

José added, “We can walk like ninjas or robots.”

The students understood that our action would be walking, but we could vary the way we were walking. I added that we could try a wobbly, sloppy, cheery, tired, or sad way, too. Our action would always be walking, but the quality of how we walked would change how the audience perceived our dance story.

I pointed out some movement quality opposite pairs I had written on the board. They were smooth/sharp, flowing or starting/stopping, and bound/free. Because my students already created previous dance work throughout a unit on movement qualities, we didn’t need to take long to review them. Nolan chose the action “skip,” and we all warmed up our bodies by skipping around the space (in a socially distant way) using the different movement qualities. We were skipping scarecrows, ninjas and robots, wobbly, tired, and sloppy. Some students added the qualities “strong” and “fast” after a few minutes of moving, so we tried skipping in those ways as well.

“I get it,” Damion said. “We could make a whole dance using only one action as long as we change how we’re doing it.”

“Precisely!” I stated, adding “When we change our movement qualities, we reshape what the audience understands as they watch our dance work.”

After we felt our bodies and brains were ready, I asked the students, “How should we make an organized and planned dance?” As they already knew, what we just did was called improvising, or letting ourselves move in any way to different prompts. We didn’t have to plan or remember our improvisations. But now, we wanted to make a plan so that we could practice it, make sure we were proud of it, and perform it for our classmates.

Damion said, “We should pick out some moments from the book and see if we can make moves for them.”

Jane added, “Our moves should have different qualities. Let’s take ideas from the book.”

The students connected to moments from the book, figuring out the links between feelings and movement qualities, and creating dance ideas. After time for a short chat with a nearby classmate and a bit of referencing the book, the students created these movement ideas:

Smooth — when the teacher says “Rigoberto” and it’s beautiful like flowers growing

Flowing — the heat lifting off the curb over summer

Bound — the student feeling bad about her lunch

Sharp — feeling upset when other kids aren’t nice

Free — when the main character begins to tell her own stories

We agreed that this five-movement dance sentence looked good, and the kids were eager to start creating. My students made choices to work alone, with a friend, or with some friends — a practice I find generates solid work by allowing and acknowledging the current feelings of students — some of whom want company and others who prefer to create in their own space. “Friends,” I said, “please remember to decide how your dances will begin and end. Also, please make sure that you remember to change your movement qualities. After all, this dance is a celebration of diversity, and just like Jane thought of food diversity, in our class we can also celebrate movement diversity.”

As the students moved through creating their dance plans, I cycled around the room to offer support and cheer on their ideas. “Remember to use as much of your body as possible so we can see your different movement qualities,” I reminded the class. I saw Raya blooming like a flower using a smooth movement quality and Jay chopping the air showing his sharp, upset movement. “I’m closing into a little ball to show my bound quality movement,” Sarah offered. The students related to the book, creating, processing, and moving.

The students connected to moments from the book, figuring out the links between feelings and movement qualities, and creating dance ideas.

After our first work period, we decided to have our preliminary showing. This is a time when our classmates can offer “glows and grows,” or compliments about parts of the dance they love, as well as suggestions for additions or changes that might make the dance even better. This is also a class habit — to keep our language positive so that our friends are motivated to keep making work they are proud of instead of saying something hurtful that might stop creativity altogether.

“OK, friends,” I said. “For our preliminary showing, half of us will perform while the rest of us are the audience. If you’re in the audience, you have the very important job of helping your friends along their dance journeys by offering feedback. Let’s remember to use kind and constructive words.” After they showed their work, Jay received the suggestion that he could use more than just his arms for his sharp action: “What about adding your legs or even your head?” Sanford got a big compliment for their bound action and the kids wondered “Can you start it with an even bigger body in order to show how small you get by the end?” For both performance groups, the audience members did their jobs; they offered specific and actionable feedback and after a quick all-around check-in, I saw that students were ready to revise their work.

Next, the children implemented suggestions they’d received or new ideas they’d like to try. I circled the room. “I love the way you’re using your whole body for this sharp part now!” I told Jay. “That really large body shape is making it much more clear just how small you’re getting,” I told Sanford. I said to Sarah that I loved the way she was using so much space for her free movement, and to Jane and Raya who had decided to work together, I mentioned that I loved the way they were passing their smooth movement back and forth; they told me that they were flowers swaying in a breeze. I loved their brilliant imagery and told them so.

By our final showing, we limited our comments to glows. I wanted the students to leave feeling proud of their revised work and satisfied with what they had created during the period. This time, each dance was performed alone in a sequence so that everyone else in the class could be the audience.

At the end of the performance round, Maggie said, “I love the way Jay used his whole body to show the sharp movements.” Damion complimented one group’s starting and ending still-shapes and said, “I could really tell when the dance started and ended.” Shelly said, “I love the way Nolan danced with five different movement qualities. I could really see them all.” Jane offered, “I like the way the dances I watched told the story in the book. We were working on ‘diversity’ today and it was cool to see all the different movement choices we made in our dances.”

After a short cool down, I wanted to close out our class time with reflections from the students. I said, “Let’s circle back, think about the BLMAS principle of diversity, Jacqueline Woodson’s book, and the dances we created during class today. Please turn and talk briefly one last time about your experience today and then we’ll see if anyone would like to share with the group.”

“I really liked the book,” Raya offered after some class conversation. “I like that there was a character who looked like me. I liked turning it into a dance because I could just make my ideas move and not have to talk.”

Nolan said, “I come from a mixed family, and I like that we are doing projects like this because we should all respect each other.”

Sarah added, “I love to dance and my body just wants to move, and using different types of energy or qualities made me feel like I was telling a better story.”

Jane offered a final comment: “We are different, we look different, we like different music, we like to dance in different ways. We are a diverse class and we should always be nice to each other.”

* * *

Through movement and sharing of dances, my 2nd-grade students deepened their understanding of the BLMAS principles and turned them into dance work. The week we read Except When They Don’t by Laura Gehl, students talked about gender stereotypes, pronouns, and what it means to be queer- and transgender-affirming. Their choreography was based on their own experiences with gender stereotypes with a final movement showing acceptance or celebration of themselves and others. During our “unapologetically Black” lesson we read The Undefeated by Kwame Alexander and made dances about Black role models.

For me, dance class is an environment in which I can foster future world changers, creators, critical thinkers, and appreciators. As we move through dance units across grades, we can learn about each other’s skills, likes and dislikes, interests, and affinities for movement and more. Creating together in dance class gives us the opportunity to connect and build empathy. We can talk about real-world topics and current events, and students can learn that movement is another communication tool they can use to help create the kind of world they’d like to have. We can use our dances as a voice for change without ever having to speak a word. We can ask each other questions and learn new things and use our bodies as tools for exploration and communication. Dance can be a transformative tool to lift students’ social awareness and inclusivity.

Students are aware of so much of what goes on in the world, and I want to create a space in which they can share their thoughts, fears, and ideas. I want students to think critically about and work against inequities so that we can live and move in a more just world.