Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action

An uprising for racial justice in education

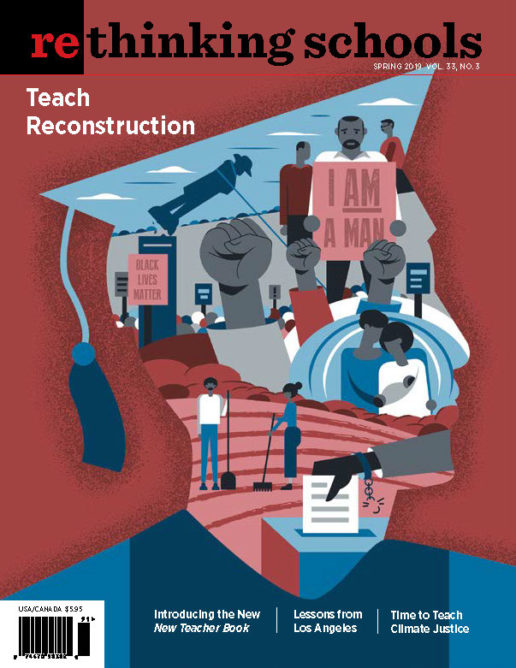

Illustrator: Joe Brusky

Joe Brusky bit.ly/Brusky_Photos

On a Sunday night at the beginning of February I got a call from my sons’ elementary school. When I answered, the recorded voice, my sons’ principal, began speaking. She was robocalling to let parents know that the teachers would be participating in the national Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action and that parents should ask their kids what they were learning during the week. I don’t think I’ve ever been emotionally moved by a robocall, but there’s a first for everything, and I was overjoyed that my sons’ own school had embraced this commitment to Black lives. I was struck in that moment about how this message represented the hard work of so many educators around the country who have been working for racial justice.

The story of Black Lives Matter at School starts with one school in Seattle, John Muir Elementary, in the autumn of 2016. John Muir had been engaging in conversations and staff trainings around equity and race and during end-of-the-summer professional development, in the aftermath of the police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, school staff read and discussed an article on #BlackLivesMatter and renewed their commitment to working for racial justice.

In support of this work, DeShawn Jackson, an African American student support worker, helped organize “Black Men Uniting to Change the Narrative” for an event at the school to celebrate Black students. The school’s art teacher wanted to show that John Muir staff fully supported this celebration of Black students and so she designed a shirt for educators that said “Black Lives Matter/We Stand Together/John Muir Elementary.”

A backlash erupted when media reported that the teachers were wearing #BlackLivesMatter shirts. White supremacists began sending hateful email to the schools and then the unthinkable happened: Someone made a bomb threat against the school. The school district then officially canceled the event, which made it smaller than it would have been, but the staff carried out the celebration anyway. John Muir parent and Rethinking Schools editor Wayne Au wrote about the action in “How One Elementary School Sparked a Citywide Movement to Make Black Students’ Lives Matter” (Rethinking Schools Vol. 32, No. 1):

The bomb-sniffing dogs found nothing and school was kept open that day. The drummers drummed and the crowd cheered every child coming through the doors of John Muir Elementary. Everyone was there in celebration, loudly proclaiming that, yes, despite the racist and right-wing attacks, despite the official cancellation, and despite the bomb threat, the community of John Muir Elementary would not be cowed by hate and fear. Black men showed up to change the narrative around education and race. School staff wore #BlackLivesMatter T-shirts and devoted the day’s teaching to issues of racial justice, all bravely and proudly celebrating their power. In the process, this single South Seattle elementary galvanized a growing citywide movement to make Black lives matter in Seattle schools.

Members of the Seattle activist group I organize with, the Social Equity Educators (SEE), wanted to support and honor the bravery of John Muir educators. SEE held an organizing meeting with John Muir teachers and decided they would introduce a resolution of solidarity in the union, the Seattle Education Association. The resolution to support John Muir, calling on every Seattle educator to wear the Black Lives Matter shirts to school on Oct. 19, passed unanimously. Yet we worried that when the day came, few would be bold enough to proclaim their belief in the value of Black lives. Then the T-shirt orders started coming in — first by the dozens, then by the hundreds. Incredibly, more than 3,000 educators wore the Black Lives Matter shirts to school, many of them including the hashtag “#SayHerName” to raise awareness about the often unrecognized violence and assault of women.

This explosion of anti-racist energy generated national media attention and teachers around the country took up the cause. That same school year, educators in Rochester, New York, held their own Black Lives Matter at School day. Then educators in Philadelphia took it to the next level. That city’s Caucus of Working Educators’ Racial Justice Committee expanded the action to last an entire week with teaching points around the 13 principles of the Black Lives Matter Global Network. They divided the principles for each day of the school week:

Monday: Restorative Justice, Empathy, and Loving Engagement

Tuesday: Diversity and Globalism

Wednesday: Trans Affirming, Queer Affirming, and Collective Value

Thursday: Intergenerational, Black Families, and Black Villages

Friday: Black Women and Unapologetically Black

The following year, educators around the country began a national week of action on the model created by the Philly educators. During the 2017-2018 school year, from Feb. 5 to 9, thousands of U.S. educators wore Black Lives Matter shirts to school and taught lessons about structural racism, intersectional Black identities, Black history, and anti-racist movements. In addition, the coalition came up with three demands:

1) End “zero tolerance” discipline, and implement restorative justice

2) Hire more Black teachers

3) Mandate Black history and ethnic studies in K-12 curriculum

The Black Lives Matter at School coalition wrote about these demands:

In this era of mass incarceration, there is a school-to-prison pipeline system that is more invested in locking up youth than unlocking their minds. That system uses harsh discipline policies that push Black students out of schools at disproportionate rates; denies students the right to learn about their own cultures, and whitewashes the curriculum to exclude many of the struggles and contributions of Black people and other people of color; and is pushing out Black teachers from the schools in cities around the country.

Educators in more than 20 cities participated in the #BlackLivesMatterAtSchool Week of Action, including Seattle, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Chicago, Detroit, Boston, New York City, Milwaukee, Baltimore, Portland, and Washington, D.C.

This year, the second annual #BlackLivesMatterAtSchool Week of Action was bigger than ever. Thanks to the great work of the NEA Black Caucus and its president, Cecily Myart-Cruz, the National Education Association passed a resolution in support of Black Lives Matter at School. Organizers also added a fourth demand for the week: “Fund Counselors, Not Cops.” Inspired by the research of Dignity in Schools, which showed that 1.6 million U.S. students go to a school with a police officer but not a counselor, BLM at School is advancing this demand to end the school-to-prison pipeline. The necessity of getting police out of schools was on display during the week of action when on Tuesday, Feb. 5, a video was released of a police officer assaulting a Black girl at Hazleton Area High School in Pennsylvania.

The following day, BLM at School organizers held rallies demanding justice and promoting the four demands.

In an era when a U.S. president calls Haiti and African nations shithole countries; a time when hate crimes are on the rise; a time when Black students are suspended at four times the rate of white students; and a time when we have lost 26,000 Black teachers since 2002, building a movement for racial justice in the schools is an urgent task.

Black lives will matter at schools only when this movement becomes a mass uprising that unites the power of educator unions and families to transform public education.

A version of this article was first published by PBS.