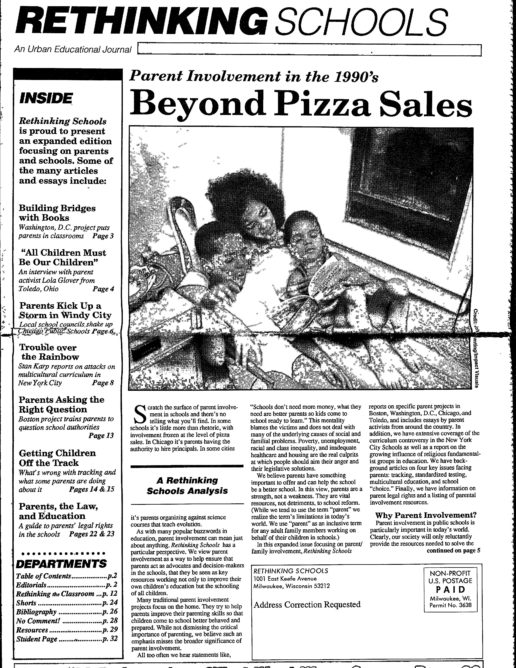

Beyond Pizza Sales

Parent Involvement in the 1990’s

Scratch the surface of parent involvement in schools and there’s no telling what you’ll find. In some schools it’s little more than rhetoric, with involvement frozen at the level of pizza sales. In Chicago it’s parents having the authority to hire principals. In some cities it’s parents organizing against science courses that teach evolution.

As with many popular buzzwords in education, parent involvement can mean just about anything. Rethinking Schools has a particular perspective. We view parent involvement as a way to help ensure that parents act as advocates and decision-makers in the schools, that they be seen as key resources working not only to improve their own children’s education but the schooling of all children.

Many traditional parent involvement projects focus on the home. They try to help parents improve their parenting skills so that children come to school better behaved and prepared. While not dismissing the critical importance of parenting, we believe such an emphasis misses the broader significance of parent involvement.

All too often we hear statements like, “Schools don’t need more money, what they need are better parents so kids come to school ready to learn.” This mentality blames the victims and does not deal with many of the underlying causes of social and familial problems. Poverty, unemployment, racial and class inequality, and inadequate healthcare and housing are the real culprits at which people should aim their anger and their legislative solutions.

We believe parents have something important to offer and can help the school be a better school. In this view, parents are a strength, not a weakness. They are vital resources, not detriments, to school reform. (While we tend to use the term “parent” we realize the term’s limitations in today’s world. We use “parent” as an inclusive term for any adult family members working on behalf of their children in schools.)

In this expanded issue focusing on parent/ family involvement, Rethinking Schools reports on specific parent projects in Boston, Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Toledo, and includes essays by parent activists from around the country. In addition, we have extensive coverage of the curriculum controversy in the New York City Schools as well as a report on the growing influence of religious fundamentalist groups in education. We have background articles on four key issues facing parents: tracking, standardized testing, multicultural education, and school “choice.” Finally, we have information on parent legal rights and a listing of parental involvement resources.

Why Parent Involvement?

Parent involvement in public schools is particularly important in today’s world. Clearly, our society will only reluctantly provide the resources needed to solve the crisis facing our public schools, particularly urban schools attended mainly by children of color. Unless we draw on the strengths and power of parents and community members, school reform will, at best, be limited to superficial efforts designed to cover up rather than resolve the crisis in education, particularly the crisis of inequality.

Parental involvement holds many promises. It can help improve the curriculum, teaching, and learning in individual schools. It can help bridge the division between many teachers and communities they serve — a division that has tended to grow, given the overwhelmingly white composition of the teaching force and the overwhelmingly non-white composition of urban student bodies. Parent involvement can also help build necessary political coalitions. If teachers and parents cannot work together at their individual schools, they will be unable to forge the city and state-wide organizations necessary to counter the slash and burn mentality that dominates many school budget decisions.

Unfortunately, some of the most successful parent organizing projects are led by arch-conservatives with an agenda that runs counter to values of multiculturalism, equality, tolerance, and respect for children as people capable of learning to think critically and make their own decisions. The success of right-wing parent organizing is a chilling reminder that there is nothing inherently progressive about parental involvement.

It was parents, for example, who threw stones at buses carrying African-American children in the mid-1970s in Boston as those children tried to exercise their right to attend integrated schools. It is parents who hide behind Bibles and shout the most un-Christian epithets as they try to prevent sex education, tolerance for gays and lesbians, and measures to counter the AIDS/HIV epidemic among adolescents in many urban areas. It is parents who often are the most virulent opponents of multicultural education and who are quick to try to ban books such as Catcher in the Rye, Of Mice and Men, and The Bridge to Terabithia.

What is to be Done?

We believe that schools should work to increase parental involvement in four areas:

1) governance and decision-making; 2) organizing for equity and quality; 3) curriculum and its implementation in the classroom; 4) home educational support. Following are some preliminary thoughts, designed to spur discussion rather than provide answers to complex issues.

Governance

Parents should be viewed as decision-makers, whether through formal or informal arrangements such as school-based councils or parent committees where their input is listened to and respected.

Key questions are: Who should serve on school councils? What should be the ratio of staff to parents to community people? How should members be selected? How can you ensure that representatives on the school council truly represent their constituents?

What powers should they have? What is the relationship between school-based decisions and district-wide policies and contracts?

These are complex issues that need thorough discussion.

Organizing/Advocacy

Organized into groups, parents can advocate for children and can educate educators. This is particularly important of parents of color, who may see inequality or insensitivity from even the most well-intentioned white teachers.

Such parent groups can take various forms, from city-wide advocacy organizations to ad hoc committees at individual schools. In Albany, N.Y., for example, parents and community activists challenged a racist tracking system (see article on p. 15). In Boston, parents are being trained to advocate for children in their individual schools (see article on p. 13).

These organizing efforts are often short-lived, hampered by funding and the many time demands on parents, especially working parents. The struggle to sustain parent advocacy groups is difficult. If such groups start receiving money from school systems, their politics might become compromised. But without funding, these efforts may die out and valuable training and experience are lost, only to be reinvented again by other parents when the next crisis erupts.

By perseverance and strong leadership, however, some organizations have managed to get funding yet not compromise their politics (see interview, p. 4). Another approach is to have community-based organizations make parent organizing a priority and to use their resources to sustain such efforts. A third approach is to demand that local school districts, perhaps funded by state legislatures, hire parent organizers at each school.

Curriculum and the Classroom

Particularly as schools try to institute multicultural curricula, parents are a valuable resource. Parents can have positive effects on curriculum, especially if their participation is organized and supported by the local school (see article p. 3). A key step is to have the school agree on an orientation toward parental involvement, in the process overcoming negative attitudes in either group. Some parents may have to overcome a legacy of negative personal experiences with schools, while some teachers need to develop greater respect for parents.

Educating at Home

We recognize that parents can significantly help their children at home. Many do, and some do not. Schools can encourage positive interactions between parents and children by helping the school serve as a center where parents can help one another. Support groups, parenting classes, and literacy classes can be very popular, especially when organized by or with the consultation of parents. Lending libraries of learning games, hands-on math activities, books, and tapes also help enhance education in the home.

Sometimes parents educate their children about the history and contributions of their cultures and communities — filling in gaps schools to often leave.

Teacher Training

Teachers need to be sensitized to the importance of parental involvement. At a district level this should include staff inservice. But most important, state mandates should force teacher training institutions to adequately prepare new teachers in knowing how to work with parent volunteers, conduct parent/teacher conferences, maintain on-going communication, and overcome possible racial, class, and gender biases.

Parent’s Rights

Parents have more rights than they might imagine. They have not only legal rights, but ethical rights: the right to have notes and newsletters from school come home in their native language; the right to be treated with respect by school staff, whether the secretary, principal, or teacher.

People who work first shift often have difficulty getting involved. Educators, labor leaders, and businesses would do good to follow the Cleveland example, initiated by the Cleveland Federation of Teachers, whereby parents are allowed to take time off with pay to attend special Parent/Family Days (see article this page).

Justice and Equality

It is in the long-term interests of everyone in society that schools are based on values of justice and equality. There is no way to legislate such values. In the long run, the only insurance rests with the parents and teachers who uphold these values to organize and work together.

No one has a stronger, more direct interest in good education than a parent. Educators who fail to recognize this, seeing parents instead as irrelevant, inadequate, or even obstructionist can never full succeed in educating young people.