As an Arab American Muslim Mother, Here Is the Education I Want for My Children

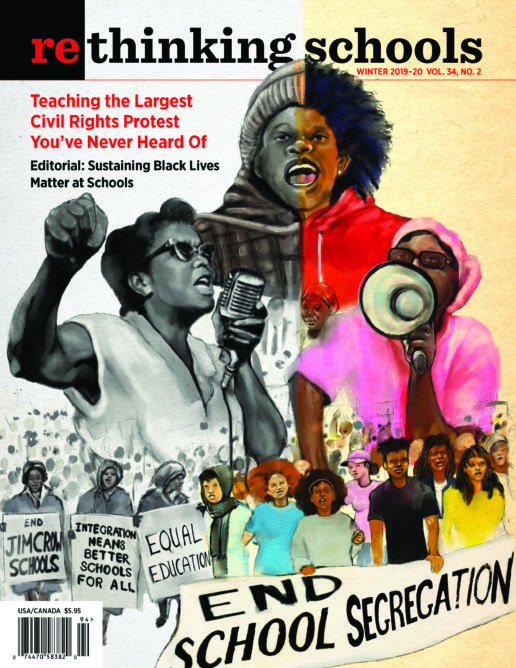

Illustrator: Leila Abdelrazaq

Of the hundreds of assignments my children have brought home from school over the years, not one of them has referred to Palestine or to Muslims. As a Muslim, a Palestinian American, and a mother, I want this to change.

My siblings and I often felt like outsiders growing up in California — struggling to find balance between our Palestinian, Arab, Muslim, and American identities. As the children of Palestinian immigrants, we knew there was something special about who we were — but this special identity is what caused that outsider feeling at times. As second generation Arab Americans, my children should not have to struggle with their identity in school as we did — but unfortunately, that is not the case.

I am an Arab American Muslim educator, born and raised in the United States. My parents were born and raised in Palestine and moved to the States in the 1960s for better opportunities following the establishment of the state of Israel and the refugee crisis that followed. My parents instilled a love for Palestine in my heart from a young age and my U.S. foreign policy lessons started at about age 3 — as the children of parents who were born in the 1940s during the British Mandate for Palestine, and the subsequent establishment of Israel on Palestinian land, we were surrounded by political discourse at breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

My siblings and I were the only Arabs at our elementary school and it was apparent at a young age that we were different. We lived dual lives: one filled with tradition and culture at home — watching Mom make fresh bread over hot stones and learning the Palestinian national anthem in preparation for a community event — and the other filled with constant attempts to blend in and maintain friends at a school where you had to shop at the Gap to fit in (as the youngest of seven, my wardrobe consisted of hand-me-downs, so Gap was pretty much out of my league). While I watched my classmates ascend from Brownies to Girl Scouts and admired the large colorful bows in their hair — I managed to make a few friends in elementary school. Once I was invited to a friend’s house to play after school and her mother commented to another parent who was over: “Nina is Palestinian . . . isn’t that interesting?” I did not think too much of it at the time but I knew even as a child, she was not making a compliment. I remember that moment decades later — now as a mother. My own experiences make me overprotective of my children, who I naturally want to shield from being “othered.”

It was not until junior high and high school that I was engaged with peers from other marginalized communities — finally feeling like I was not an outsider. Most of our peers thought my siblings and I were Mexican and our dark hair and brown eyes allowed us to blend in rather than feel “out” as we did at the predominantly white school that we attended previously.

In college I made Arab and Muslim friends (other than my siblings and cousins) for the first time, on my large university campus in Northern California. I was able to celebrate and further cultivate my love for the Palestinian traditions and culture my parents taught me by getting involved in social and political activities on campus and in the community. As an undergrad student when the second Palestinian Intifada and second war in Iraq started, there were plenty of opportunities to join protests against U.S. involvement in the Middle East. These protests were not just about opposing war in Iraq though — they became a meeting place for like-minded activists to gather and speak out against U.S. global hegemony and the unfair foreign policy the United States supported regarding Palestine.

Hopes for My Three Children

Now, as a mother of three children, I reflect on my own life as I attempt to navigate parenthood. My daughter and two sons are second-generation Arab American Muslims. Their grandparents on both sides were born and raised in Palestine. In terms of “fitting in,” not much has changed since I was their age. My children also attend a predominantly white school as I did. The reality is that my children are Arab American Muslims with Arabic names and the only time they hear any mention of Arabs or Muslims in America on TV is from the news and they hear “terrorist, threat, or war” associated with Arab, Muslim, or Palestine. At school, the first and only time that my son came home to tell me that Arabs and Muslims were discussed at school, it was in the context of learning about the horrific acts of Sept. 11, 2001. He was confused and disheartened, yet adamant that real Muslims would not kill innocent people. My response was to sit my three children down and teach them how to engage in a discussion about Islam when they are confronted with a situation where their religion or identity is misinterpreted at school. In the 4th grade, when children are taught that Muslims are terrorists, as in this teacher’s September 11th lesson, how are they supposed to process who their Muslim classmates are? Especially at a time when the president openly supports anti-Muslim racism.

My children are asked questions about their faith and heritage by other students and are too young to discern if the questions are out of curiosity or fear, just like I endured. “Why don’t you celebrate Christmas? Do you believe in Jesus? What’s Palestine?” can be difficult questions for very young children to answer when put on the spot. Teachers who are oblivious of the background or culture of my children typically do not intervene or discourage students from asking personal questions, much like my teachers in elementary school.

The school curriculum does not attempt to offer understanding from a global perspective so it is no wonder the students turn to my kids with questions. Between my three children and the hundreds of assignments they have completed over the years, I have never witnessed a homework assignment or class assignment refer to Palestine, Arab Americans, or Muslims. Whether it is Palestine, the history of Arab Americans or the fact that Muslims have been in North America for hundreds of years, not one reference that I am aware of has been made.

When geography is studied, even when in the context of ancient civilizations, there is no mention of Palestine in the classroom. Curricular silence is not an attempt to remain neutral — it is an acceptance of the Western-dominated narrative that fills our social studies books in U.S. schools. Although some lessons may explore “ancient civilizations,” the historical contributions of Muslim scholars (such as the creation of algebra and discoveries in astronomy) are ignored while Western civilization remains at the center of the curriculum. So far, my children have not had an opportunity to write, present, or share in any capacity their heritage with their classmates. Even at my elementary school, I remember we were invited to dress up in cultural clothing and share a traditional dish with our class in 3rd grade. (My teacher was Greek and appreciated cultural exchange.) My children are now in 2nd, 4th, and 7th grade, and I cannot recall a time when teachers provided such an opportunity. This may seem like a simple example, but the validation that such opportunities provide can have a lifelong impact on how a student views their identity in relation to their classmates, in their community, and within the national conversation.

We live at a time when the president has expressed disdain for Brown and Black communities. The president backs a Muslim ban, openly encourages anti-Muslim and anti-Arab racism, has halted Syrian refugees from entering the country, and wants to build a wall to block families searching for safety. The current president also has given every stamp of approval needed for Israel to continue its settler colonialism and military Occupation of Palestinian land — my parents’ and my grandparents’ homeland. Palestine is typically not in elementary world history books and my children ask me why Palestine is not on the maps they study at school. I respond, “Palestine exists — it’s where your grandparents and great-grandparents were born,” and regardless of which map they see, they know where to find Palestine. Now, when we come across a globe in a store, my kids always point out where Palestine is — regardless if they see Palestine printed there. Of course, we discuss their heritage and family lineage at home, just as we did when I was growing up, but it would be great to have reinforcement from school, not an erasure of my ancestors’ homeland. One of my boys has an affinity for studying flags and asked me why the Palestinian flag is not in the almanac he checked out from the school library. Non-Palestinian students wouldn’t even realize Palestine was missing. Why should children have to wait until they get to college to learn the truth? And that is if they opt in to explore such topics.

My Children’s Teachers

My children do not see a reflection of themselves in their teachers. Although the student demographics are shifting at the school they attend, every single teacher in their school (with the exception of the physical education teacher) is white. I have a hard time believing this wasn’t intentional when I see that every administrator and school board member is also white.

I must mention that my children have had some great teachers at their school. However, there was a year that I received so much critical feedback about one of my children (in kindergarten!) coupled with the hostile demeanor and negative tone of the teacher during every conversation I had with her, that I couldn’t help but think, “Does she have a problem with my child because he’s Arab? What assumptions are made about my child because of his name?” Regardless of being U.S.-born, a name with cultural significance defines you in this country. Names pay homage to your ancestors . . . or in my daughter’s case, to her grandmother who was born in Palestine. The beauty in the range of students’ names is rarely recognized but can serve as a rich lesson to learn about the heritage of the children in a classroom.

The lack of diversity in the teachers at my children’s school (and any school) is reflected in the curriculum, in the lessons, in the molding of every child in each classroom. As I see an influx of children who are Muslim and/or of Arab heritage at my children’s school, I wonder when the administration will make adjustments to welcome this population.

One lesson on Islam or Arabs — is that too much to ask? It can be as simple as inviting a parent to speak about why their child is fasting during Ramadan at school. I believe it is reasonable for teachers to recognize when children are fasting and to have a conversation with the class about what this means so children are not confused about why their classmates aren’t joining them at lunch. Regarding cultural traditions and practices, it would be great to solicit suggestions from parents about how their heritage can be shared in the classroom as a way to educate their child’s peers about global customs. I know many parents would be happy to share information.

Keeping Hope

Unless parents, educators, and advocates for social justice speak out against the status quo that controls the curriculum in our schools, nothing will change. I am not the only one wrestling with how to raise proud Arab American Muslim children while countering the hostility that exists toward Arabs and Muslims in our society. Is it too much to ask that teachers simply recognize children for who they are? For teachers not to pass judgment on their students or their families and to make attempts to celebrate the heritage of all children in their classrooms? I hope that it doesn’t take another generation for us to witness a more expansive social studies curriculum that includes Palestine and the history of U.S. involvement in the Middle East — from the perspective of the people who are from the region.

With the struggles, there is also triumph. One day when my children are my age, and they reflect on their childhood, they may recall children who asked them curious questions and ignorant teachers who didn’t acknowledge their faith or heritage and a time when we had a racist anti-Muslim president.

But that’s not all they will remember. I hope they remember this moment when not one, but two American Muslim women, one of Palestinian heritage, Rashida Tlaib, and the other of Somali heritage, Ilhan Omar, were elected to Congress. These are the women we sometimes discuss at our breakfast, lunch, and dinner table — leaders who offer hope and that my children can strive to emulate. It was the election of these women that prompted Scholastic News to publish an issue focused on the newly elected women in Congress that included Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar on the cover. That is progress toward telling stories to our children that are not in the social studies text (yet!).