Preview of Article:

An Unfortunate Misunderstanding

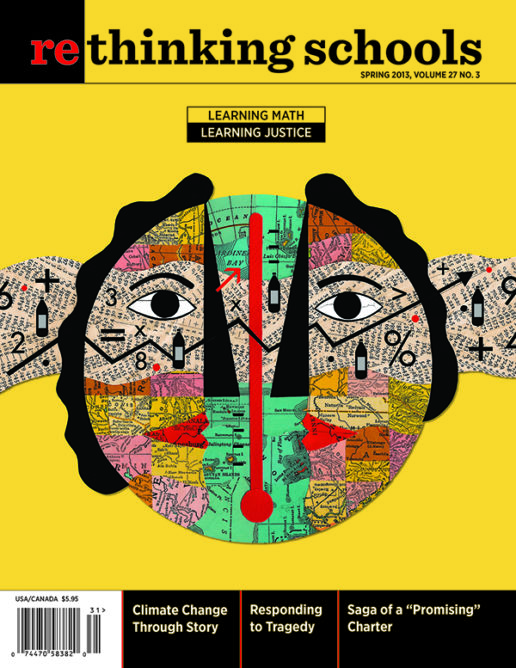

Saga of a promising new charter

Illustrator: Spencer Walts

I was nervous as I started the conversation. I was talking to a mentor of mine—an experienced teacher and administrator who I look up to as a staunch defender of public education—and I needed some sort of absolution. You see, although I think of myself as firmly against attempts to fragment and privatize public education, I was going to work for a charter school.

I had a couple of ways of justifying that decision. The charter school, which was just starting up, had a wonderful educational philosophy and would be using first-rate curricula—workshop-based, experiential, project-oriented—a far cry from the scripted curricula I had been forced to work with in my previous school. It was located in a diverse urban neighborhood where many public schools had been shut down, presumably leaving families with few good options for where to send their children to elementary school. I was told this new school had ties to a successful community preschool that had been operating for many years. And the principal who had hired me was an open, welcoming person with a strong vision for the school as child-centered and project-based. Though not from the neighborhood herself, she was African American and had a profound level of respect for the historically African American community in which we were working. She made deep connections with families and I loved watching her talk to the students.

As I explained all of this to my mentor, a wistful look crossed her face. She didn’t particularly like the idea, but told me, “You have to do what you have to do. You have to see what it’s like.”

“I’m worried,” I said, “but it’s a once in a lifetime opportunity. I’ll have the chance to help create this school from the ground up.”

Almost a year later I would find myself in a different room, talking to Carol, a board member and another powerful woman, and saying almost exactly the same words: “When I took this job, I imagined that we—teachers, parents, administrators—would be able to shape this school into the kind of school we all really wanted. I didn’t expect the structure to be so top-down. I thought we were all creating a school together.”

Her response, as she accepted my resignation, was succinct: “I’m sorry you misunderstood.”