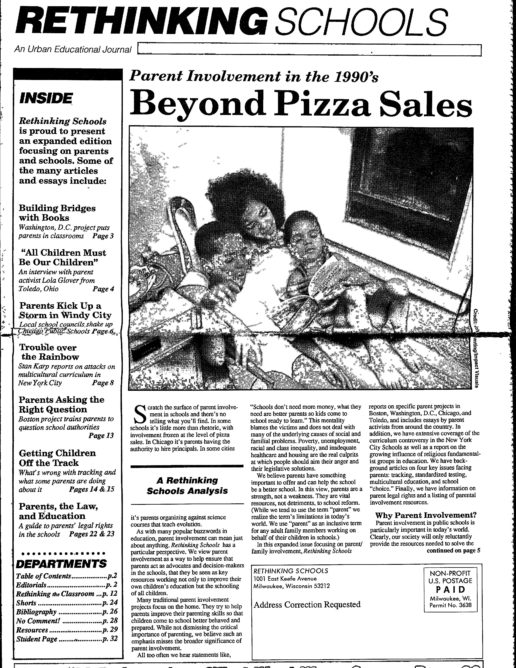

‘We Must Act as if All the Children are ours’

Interview with Parent Lola Glover

The following is condensed from an interview with Lola Glover, head of the parent and community-based Coalition for Quality Education in Toledo, Ohio. Glover is also co-chair of the National Coalition of Education Activists, and co-director of the National Coalition of Advocates for Students. She was interviewed by Barbara Miner of Rethinking Schools.

How did you get involved in education?

I’m the mother of nine children and I started the way most parents do. And that’s the PTA, Mothers’ Club, room mother, chaperone, chairperson for the bake sales, that kind of thing. This was 30 to 35 years ago.

Because I was at school a lot, I began to notice things that I felt were not conducive to the educational or emotional well-being of students. I began to realize there was a pattern to certain things, instead of something I observed for one day. I began to question those actions, or the lack thereof, and to talk more to my own children about school. It was then that I started to get involved in my children’s actual schooling and in academic issues.

I always made sure, however, that I was active in such a way that all the students in that particular classroom or school would benefit, not just my child. When I advocated only for my child, not a lot changed. The teachers and administrators would just make sure that when I was on the scene or when they dealt with my child, they would do things different.

I don’t believe that we will ever get all of the parents involved in the ways that we would hope. I believe that those of us who have made a commitment to get involved must act as if all the children are our children.

Do you sense that some teachers are reluctant to have parents involved in more than homework or bake sales, a fear that parents are treading on the teachers’ turf if they do so?

Absolutely. And I don’t think much of that has changed over the years.

Let’s say I’m a teacher, and I come in and do whatever I do in my own way, in my own time, and nobody holds me accountable in any way for providing a classroom environment conducive to learning, or for student achievement. I get pretty set in my ways — and defensive with people who might question what I do.

I’ve found the teachers who are reluctant to have parents involved are those who know they are not doing the best they can for their students.

Then there are some teachers whose degree gave them a “new attitude” and who question these folks who didn’t graduate from high school, and surely didn’t go to college. Such teachers question what these parents are doing in their classrooms. It doesn’t matter that they are the parents of their students.

I also have found some really great teachers in our district. They don’t have any reservations or problems about parents getting involved in their classroom or school. In fact, they welcome and encourage parent involvement.

Many parents don’t necessarily have time to sit in on their child’s classes or visit the school on a weekly basis. How can such parents make sure their kids are getting a decent education?

Not all schools have parent organizations at their schools. But usually you find a few

active parents who are great advocates for children. If you know you don’t have the time and energy to be actively involved, touch base with those parents that are involved. Build an alliance with them, get on the phone with them and when you can, meet with them and talk about your concerns. Help in any way you can to assist in developing an organized parent group in your school.

You don’t need all the parents in the school to be involved. Sometimes it just takes five or ten dedicated parents who care about kids, and not just their kids, to make a positive difference in what goes on in our schools.

What advice do you have for parents who want to get involved?

First of all, you have to understand that as a parent, it is your right and your responsibility to be involved. You should let the school know that you would like to work together in a constructive and collaborative way if possible, but if not, you’re still going to be there.

I would also find out if any parent groups exist in the school. I would try to determine whether the group is really involved in making a difference for kids, or whether it’s just a rubber stamp with no voice. You also have to decide whether you want to be involved in decision-making, or in things like fund-raising.

If you want to get involved in school policies, you must first know the rules. If you are interested in suspensions or expulsions, for example, you must ask for a copy of the discipline policy for the district, not just the school. Then you must find out if there is an individual school policy or practice that goes beyond the district policy.

Then you must sit down with the principal and say, “I understand that this is your policy on discipline, but this has been your practice in this building for x number of years, and these are some of the areas I’m concerned about.”

It’s also essential that you always try to get a neighbor or a friend or another parent to go with you when you talk to the principal or teacher. My experience has taught me, do not go alone.

Why?

Words get twisted, views get changed. People in schools are no different than anyone else. They will say, “Oh, that’s not exactly what I said,” or, “I didn’t mean it that way.” If there’s another person with you, they tend not to try to get away with that kind of stuff because they know more than one person will hear what they are saying.

Some schools face severe budget cuts, and teachers have larger classes and are asked to do more and more. What if the teachers and administrators say, “Parent involvement is great, and I would love to have more meetings, do parent newsletters, visit kids’ homes, and have parent committees, but I barely have time to prepare lessons every day.” How would you respond?

Parents have to do more than be involved in their school or district. They also have to respond to elected officials. And if more money is needed for education, let your thoughts be known. Everybody claims to be either the Education Mayor, or the Education Governor, or the Education Somebody. Parents need to lobby and fight for those funds.

Another area of concerns is class sizes. With the kinds of problems kids bring to school today, either the classes need to be smaller or there needs to be teacher aides in the classroom. And these aides should be parents or people from that school community. This allows some additional time and a resource for teachers.

How can teachers and principals make parents feel more welcome?

The district or each school should have a parent outreach program. One of the biggest mistakes that teachers make is not being in touch with parents until there’s a problem. And most parents don’t want to hear the problem. They would like to think that little Johnny or Mary is doing fine all the time, and if not, they don’t want to hear you putting their kid down. If you start off that way with a parent, it will take some real doing to get on the right foot with them again.

It’s not going to be easy to build an alliance with 30 parents, so start with one or two. Get those parents to be your liaisons. Let them know how much you care and what you are trying to accomplish in the classroom. Give them the names and addresses of parents of the kids in your classroom, and ask, “Would you help me contact these parents and explain to them that I would really like to talk to all of them personally.” Find out when will be a good time for everyone to meet, and set a date.

Why is it so important to foster mutual respect between parents and teachers?

I am convinced that if students begin to see parents and people in their community and their schools working together, a lot of things would change. First of all, the kids’ attitudes would change. Right now, kids’ attitudes have not changed about school because they don’t see any connection between home and school. They do not see any real efforts being made by either side to come together for the purpose of improving their schools or educational outcomes.

I don’t think any of us have the answers to solve these problems. But I do believe that if we come together out of mutual respect and concern, we will make a difference in what happens in our schools and our communities. I know we’ll never find the answer if we keep this division between us. For the sake of our children, public education, and our future, we can ill afford not to work together. Make the first move.