40 Acres and a Mule

Role-playing what Reconstruction could have been

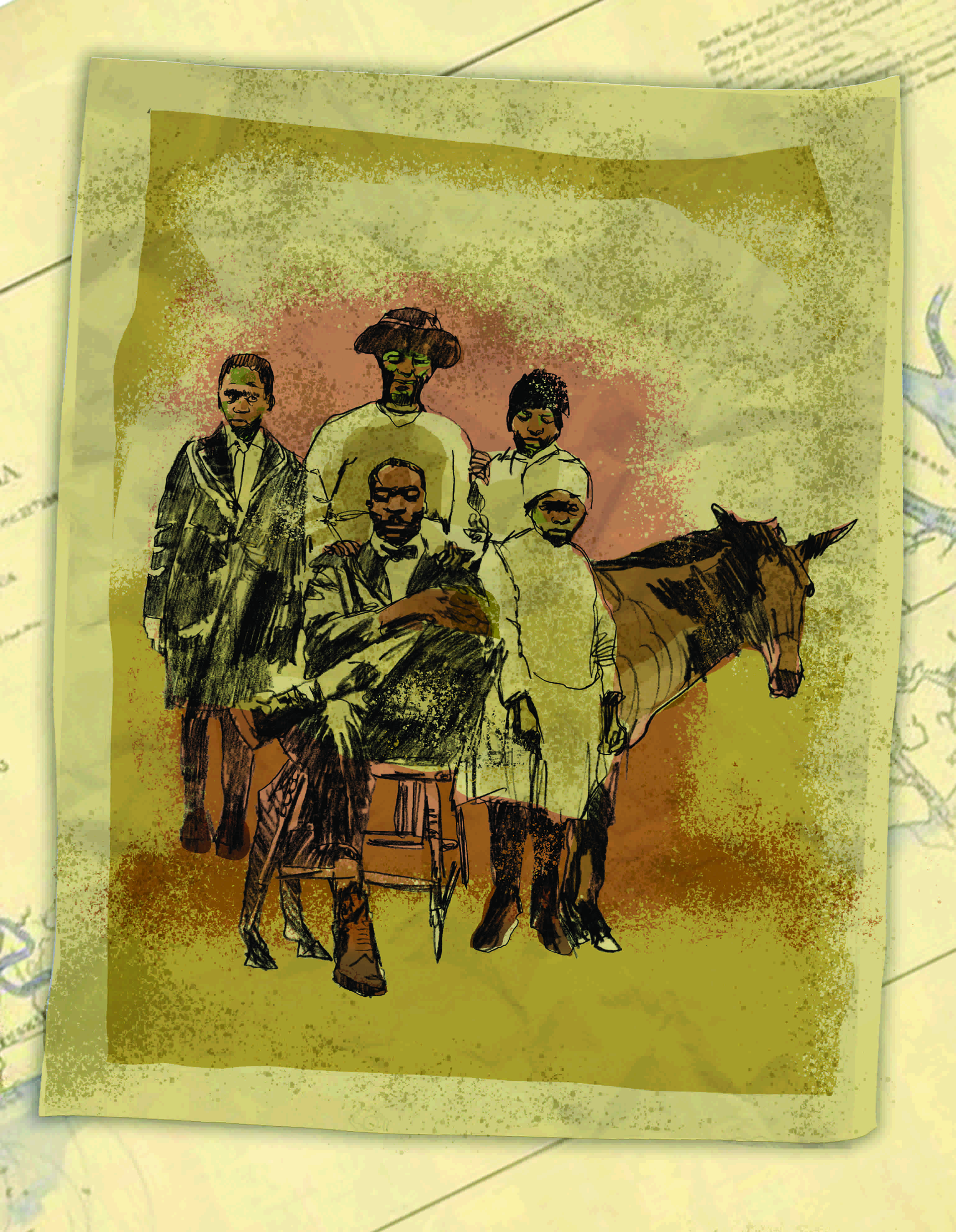

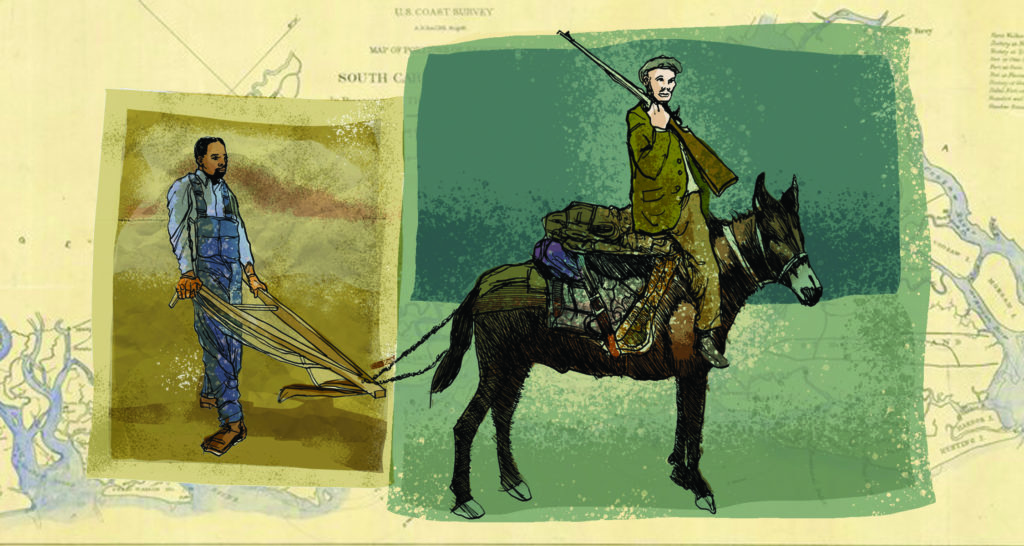

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

There are moments in history that give us a glimpse of a different world — moments that force us to wonder if things could have turned out differently. One of those moments occurred at the end of the Civil War in 1865 on what are known as the Sea Islands of the Georgia and South Carolina coast. Freedmen and women divided up land, planted crops, started schools, and created a new society in the ashes of the old.

Many historians term this experiment in grassroots democracy and Black self-determination that occurred in the coastal Sea Islands a “rehearsal” for Reconstruction. But the Sea Islands experiment was more than a rehearsal; subsequent Reconstruction plans lacked the key ingredient that made it revolutionary: the redistribution of land.

For a brief moment in U.S. history, the property of some of the wealthiest people was handed over to some of the poorest. The story of what happened to the land illuminates so much of what was possible and what went wrong during the Reconstruction era and helps us better understand how racism and inequality still shape the United States today.

As a high school history teacher, I wanted to design a lesson that would both introduce students to the ways African American life changed after the Civil War and take them through the dramatic story of the Sea Islands. I created a multiday role play that utilized creative writing, map-making, and film clips to introduce students to this crucial chapter of early Reconstruction history that set the stage for the battles to come.

Role-Playing Freed Families

Social studies teacher Mark Cichon invited me into his Hillcrest High School classroom in Queens to teach this lesson to his 12th-grade government class. Mark’s class resembled the overall school demographics: almost entirely students of color and evenly split between Black, Latina/o, and Asian students. More than 80 percent of the students at Hillcrest receive free or reduced lunch.

After a quick review of the Civil War, we jumped into the role play. I asked Mark to group students into six “families” that would stay together throughout the weeklong lesson. Then I started explaining to the class that to learn about the Reconstruction era, we would start in Georgia immediately following the Civil War.

“Something remarkable happened there,” I told them.

After explaining to students that they were grouped into “families,” I passed out a role sheet that would set the stage for the lessons to come:

In the final months of the Civil War, Union Army General William Tecumseh Sherman had a problem. He had marched 60,000 Union soldiers 285 miles from Atlanta to Savannah, Georgia, striking fear into the Confederacy and landing a decisive blow for the Union. But along the march thousands of newly freed people began following Sherman’s army. Finding housing, employment, food, clothes, and medicine for the refugees soon became impossible. Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton decided to hold a meeting with a delegation of Savannah’s Black leaders to get their advice on what to do with the 10,000 formerly enslaved people now marching with Sherman’s army. Garrison Frazier, a Baptist minister and the group’s spokesman, made clear the demands of the freedmen and women: “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land.” Four days later, Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15. The order redistributed 400,000 abandoned acres of land, in 40-acre plots, to newly freed Black families. Later Sherman agreed to lend Black settlers army mules to work the land. This gave birth to the famous phrase “40 acres and a mule,” as a small reparation for years held in slavery.

Before the war, you lived with your family on the Sea Islands of Georgia. You were enslaved and worked on the coastal plantations for some of the richest slave owners. . . . While you worked in the hot sun, your “owners” usually retreated to better weather in Savannah, Charleston, or New York. Under slavery, you were forced to work, farming rice and cotton. Those crops were sold and the profits made your “owner” one of the wealthiest people in the country. They lived in luxury, while you barely survived. Even when your “owners” left the plantation, they hired overseers to make sure you continued to work. If you didn’t do as you were told or tried to escape, you were subject to severe beatings, whippings, and possibly even death.

But when the Union Army came to the Georgia coast, your “owner” again left the plantation — this time, you hope, for good. You are now free. Your freedom means that you can leave the plantation, but Sherman’s Field Order means that you can stay, claim 40 acres of land for your family, and start a new life.

When we finished reading, I distributed instructions for the first activity. My goal was to have students grapple with both the legacy of slavery in defining Black family life in the postwar South, as well as the important changes freedom brought. I gave each group of students a different surname from one of the wealthy slave owners who had ruled the Sea Islands before the Civil War and created four short scenarios to draw out some of the key aspects of postwar life for formerly enslaved African Americans. As a group, students discussed each scenario and decided which individual roles each student would play in the family. After discussing all four, they wrote individual interior monologues or diary entries about one of the scenarios.

In the first scenario, I had students look at advertisements that were placed in the personal or information-wanted sections of Black newspapers across the South in hopes of locating family members who had been sold as a result of slavery. I changed the surnames in the ad to reflect the family names the students had been given. In each group, I asked students to “determine who is looking for whom in the advertisement. Assign the names in the advertisement to people in your group.”

Angela wrote about the joy of being reunited with her children, “I am so happy that we found Nancy, Ben, and Tempa. . . . It felt like my soul was being torn apart when we were all separated. Thank you, God, for returning my three children to me. It’s hard to explain the joy I feel now that we are back together.”

The second scenario involved a family heirloom. Borrowing a strategy another Rethinking Schools editor learned from Toronto teachers at a conference on teaching apartheid in South Africa, I carefully gathered real objects for the lesson because I wanted students to be able to physically connect with something, but printing out images of objects could have also worked. I passed out one object to each group: a blanket, a necklace, a photograph of a Black soldier, a map of the Georgia and South Carolina coast, a wooden cup-and-ball toy, and a leather journal. Each one “is an object that your family would never part with,” the instructions explained. “Invent a backstory to this object that helps us understand your family and why this object is so important to all of you.”

The stories students came up with revealed both the horribly repressive nature of slavery and the various ways enslaved people resisted. As Ankur wrote, “This toy has been in my family for generations . . . it’s one of the things that helps me escape my traumatic past. Knowing that this toy has been passed from child to child, it helps me feel connected to my siblings, some of whom were sold off before the war.” Corina wrote that for her family, the map they received “represented our freedom as it pinpoints the location we would meet if we managed to escape slavery together.”

The third scenario asks students to imagine they either took part in or witnessed one of the mass wedding ceremonies that occurred in the aftermath of the Civil War. As Allie explained in her diary entry, unlike under slavery, an official marriage license meant that husbands and wives could “now claim each other, their children, and their property,” all of which enslaved people had no legal claim to. “For these reasons” as the handout explains, “many newly freed couples were eager to obtain an official marriage license and hold a public ceremony to celebrate unions that had received only partial recognition under slavery . . . mass wedding ceremonies involving as many as 70 couples at a time became a common sight in the postwar South.”

And finally, I asked students to decide whether or not to change their family’s surname. As the handout explains, “During the war, many Black soldiers began using new last names as a way of asserting their new freedom. Others chose to maintain their old surnames as a tie to their birthplace and ancestors or to make it easier for lost family members to find them. Now it’s time for your family to decide.”

“We’ve come a long way. Our family has been enslaved for generations, but now that we are free, everything is different,” Patrisse wrote about her group’s decision. “One thing, however, still doesn’t feel right. It’s our surname. For so long we’ve been addressed by the name of our brutal slave owner. However, now that we are free, we are changing our name. . . . This new name will finally free our family from our horrible past.”

After giving students a chance to write about their stories, they read their writing to the other members of their group. Each group picked one piece of writing to share with the larger class and gave all of us a sense of the family backstory they had discussed together.

It took one 45-minute class period for students to discuss each scenario, and another 45-minute class period to write and share their stories. By the end of the two days, students seemed proud of the stories they created. But to capture the story of freedpeople in the Sea Islands, I wanted them to also experience — as much as one can in a classroom — what it must have felt like to build a new society out of the ashes of the old.

Mapping Out 40 Acres and Building a Community

For the next activity, I used an online map creation tool from RollForFantasy.com to make maps where students could plot out their family’s 40 acres. I also created a handout that provides some basic information about how land passed into the hands of freed families:

General Rufus Saxton, currently in control of the Georgia and South Carolina Sea Islands, has demanded General Sherman’s order be enforced and has named Tunis Campbell, a Black Northern abolitionist, as superintendent to help settle freedmen and women on St. Catherine’s Island on the Georgia coast. Campbell has split up the island into 40-acre plots for each family. . . . Campbell has been in touch with Northern missionaries and abolitionists who have created freedmen’s aid societies. These organizations have donated clothing, seeds, plows, and hoes. Your family must decide what your priorities are for your land: What do you want to grow? Many people are watching this experiment in the Sea Islands, so it’s important that you, your family, and your community prove that you can make it on your own.

To reinforce this information and give students a visual of the Sea Islands, I played a short clip from PBS’s Reconstruction: The Second Civil War (Part 1, Scene 5, 23:02–25:42). During the clip, historian Eric Foner explains, “There were a lot of people in 1865 who were trying to tell Blacks what freedom is and tell them what they ought to be doing. [Tunis] Campbell reflects the impulse ‘We should really determine ourselves what we’re doing.’ Independence from white control — that’s critical to their definition of what freedom is.”

After the clip we returned to the handout and went through the instructions for creating a map of their family’s 40-acre plots. The instructions take students step-by-step through the process of creating their map. Students determine what acres on their map are tillable, decide where they would like to build their family’s new home, and debate whether they want to produce cotton to sell or food to grow for subsistence. Finally, following simple guidelines, students indicate with colored pencils where each crop is grown on their map.

The main learning that occurs during this map activity comes in the decision about whether or not to grow cotton. The handout emphasizes that “Many in the North . . . want you to produce cotton to sell up North. Northern industries depend on a supply of cheap cotton from the South and they want you to continue selling to them.” But like the newly freed people on the Sea Islands, most students are reluctant to grow a crop they can’t eat and is associated with slavery. The idea of building a community that can sustain itself by growing its own food is attractive.

When students finished coloring their map, I had each group roll a die to determine how well their first crop did. As the handout explains, their die roll determines whether their family ends the growing season in debt, breaking even, or with a profit. If students choose to grow cotton, there is a higher risk their family won’t break even, but also higher possible profits. At Hillcrest, every group chose to grow food, not wanting to be dependent on white cotton dealers and the ups and downs of the market. With several high rolls, only one group ended up in debt, with almost all groups having a profit at the end of the day.

The next day, I sat students in a circle and went from family to family asking each to remind me how much money they made the day before. This is important because the questions we were about to debate ask students to sacrifice some of this money for the greater good.

I then played another short clip from Reconstruction: The Second Civil War that shows the community on the Georgia Sea Islands thriving. After quoting a letter from Campbell that discusses the various crops planted, the narrator describes the government the community created: “There would be a Congress with eight men in the Senate and 20 in the House of Representatives. A Supreme Court, and Campbell himself as president” (Part 1, Scene 5, 25:42–26:50). I stop the clip immediately after the sentence above, before the narrator mentions the militia.

Next, I told students that for this lesson I would play the role of Tunis Campbell, who has convened a “community meeting” with all the families on the island. I then gave a handout to each student outlining the two key questions we would discuss: Do you want to devote time and money to building and maintaining a school? Do you want to devote time and money to forming a militia? Each question is introduced with some background. For example, question two begins:

Jacob Waldburg, the prewar owner of St. Catherine’s Island, is back in town and demanding that his land be restored to him. . . . In addition, the community on St. Catherine’s Island has increasingly become a symbol of Black freedom and self-determination. Many of you are worried that the community might become a target for whites on the mainland. . . . Campbell suggests that the community pass a law to keep white people off of the island and set up an armed militia to enforce the law.

Because almost every group had money to spare after the previous day’s die rolls, spending some of it to set up a school and a militia seemed like a no-brainer. Nevertheless, a few students still questioned both ideas. Brandon argued, “We made a ton of money yesterday. We’re already doing so well. Why do we need schools?” But Sequanna replied, “How do you know we’ll always be doing well? What happens when we’re in debt and we can’t read or write? We could easily get taken advantage of.” Lori added, “And there was a reason white people didn’t want us to read in the first place. They wanted to keep us in a lower position.”

After students made a decision to fund the school, I played another short video clip from Reconstruction (Part 1, Scene 8, 38:49-43:05) that details the tremendous efforts freedpeople made on the island to gain an education and sets up the second question by discussing the return of Waldburg demanding his land.

The next debate was more controversial. Although most agreed a militia should be formed for protection, especially from Waldburg, banning all white people from the island did not sit well with several students. Ali argued, “You can’t fight racism with racism and that’s what we’re doing if we ban all white people.” Brandon added, “Also we could sell white people our crops. Why do we want to ban them?” Nathan disagreed, “Most white people were racists, they’re not coming on to our island to buy food from us. They’re coming to mess up the community we created.”

Students decided against the law. I explained that in reality, the Sea Islands government did indeed ban white people from the island and enforced that law through their militia. As the bell was about to ring, we briefly discussed why people on the Sea Islands might have passed this law in contradiction to what our class decided.

Responding to Presidential Reconstruction

Listening to their passionate discussions, it was clear that students had become deeply invested in the community they had created. So while learning what happened next was tough on students emotionally, I felt like it was important to give them a small taste of what it might have felt like for the people of the Sea Islands to lose their land.

When students returned to class the following day, I informed them that something terrible had happened: “The president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, has been shot. The vice president, Andrew Johnson, is being sworn in as the new president.” I then turned to another clip from Reconstruction (Part 1, Scene 9, 47:00–51:38) that discusses the ascension of Andrew Johnson and his policy of pardoning thousands of former Confederate plantation owners. In the clip, historian Russell Duncan explains, “The planters only want to be pardoned so that they could get their land back. And so Andrew Johnson complies with their wishes, pardoning 15,000 to 20,000 planters, hundreds of them being pardoned every day. When these planters then are pardoned, they return to their islands and to their acreages all over the South, and they want the people who are then living there removed.”

I end the clip after a scene that reenacts a powerful meeting on Edisto Island in South Carolina. General O. O. Howard, the head of the Freedmen’s Bureau, established by Congress in 1865 to help formerly enslaved people, travels to the island to meet with freedpeople who had been living independently in the Sea Islands. He explains to them that they must return their land to its prewar owners. I stop the clip after a quote from a letter sent by representatives of the Edisto Island community: “You ask us to forgive the landowners of our island . . . the man who tied me to a tree and gave me 39 lashes, who stripped and flogged my mother and my sister and will not let me stay in his empty hut, except I will do his planting and be satisfied with his price — that man I cannot well forgive.”

I then explained to students that Johnson’s new policy means that the land and the community that they have been cultivating is also now in jeopardy. I asked them to write their own letters — either to President Johnson or General Howard — about why these lands should not be returned. The letters students wrote were full of anger and anguish. Shaunté wrote, “I must have been a fool to believe that we had some type of freedom in this country. For many years I have suffered, been beaten, and robbed of my education all because of my skin color. Once again, my rights as a human being are being taken from me. This land that I put my blood, sweat, and tears into is going to be given to the people who have done nothing but rob us of everything.”

Josh pointed out the debt that the country owed enslaved people: “We deserve this land! Our family has been tortured by this man. We’ve been beaten and treated like animals. So as a punishment you give them their land back? We refuse to give up this land. It’s the least this country can do for us. We refuse to become someone else’s laborers again. We refuse to work for a white man and live a miserable life. We deserve better!”

After students shared their letters with one another, I presented them with a final decision to debate as a community:

In January of 1866, a battalion of Black U.S. Army soldiers arrive on the island with orders to protect (the prewar owner of the island) Jacob Waldburg’s property rights. Waldburg has rented the plantation to two white Northern capitalists who want the freedmen, women, and children to sign labor contracts with them. These Northern capitalists hope to return all the land to the production of cash crops.

There is a debate in your community about how to respond. Of course, if you chose to create a militia, you could try to fight. But you’d be going up against the U.S. Army — even worse, you’d be fighting other African Americans. Some argue that as hard a pill as it is to swallow, if you want to stay on the land you invested so much time in, the land of your ancestors, you have to sign contracts to work for these Northern capitalists. Others argue that it’s time to leave. When you were enslaved, you couldn’t leave the plantation without your owners’ permission, but now you’re free to leave and find work elsewhere — maybe you could even use the money you’ve saved up to buy land somewhere else.

Students argued forcefully against Nathan, a particularly defiant young man who wanted to turn their militia against the Black U.S. Army troops. While it quickly became clear the class would not fight the Army, the decision on whether to stay or leave was not as easy. Many of the family groups had built into their storyline that they hoped to find a relative who had been sold away under slavery. They worried that if they left they might never be able to find that person. Ultimately, the class decided that this was a decision that each family had to make for themselves. Like in real life, some decided to stay and others to leave.

When the class finished debating, I told them the real historical outcome of both groups. Those who decided to stay initially signed contracts for high pay, but at the end of the season the new white Northern owners of the land refused to pay them. Like many freedpeople across the South they engaged in a long battle with new white employers over pay and working conditions. Those who left, led by Tunis Campbell, established another Black cooperative community farther inland in McIntosh County. This county became a center of Black Power during Radical Reconstruction in Georgia and was the base upon which Campbell was elected both justice of the peace and representative to the Georgia State Legislature in 1868.

Lessons from the Sea Islands

When students returned the following day, I had them step out of their roles to write and discuss the role play they had participated in over the course of the week. I asked them:

• What emotions did you have after finding out you would lose your land? How do you think freedmen and women who participated in the Sea Islands community felt when they lost their land?

• Why do you think the U.S. government decided to give former plantation owners back their land?

• Was Andrew Johnson solely responsible for what happened? Who could have challenged him?

• Was there anything freedpeople could have done to keep their land?

• Why was land so important to newly freed people?

• Is this story simply a tragedy? Is there anything that brings you hope?

The next time I teach this lesson I want to add questions about how this history helps us understand race and racism today. My main regret in implementing the lesson is that most of our discussions remained in the past. I also wish I had spent more time asking students to reflect on their experiences during the role play and what had stuck with them. Nevertheless, students’ answers revealed how well this role play had introduced them to the larger themes of the Reconstruction era.

About the people who had participated in the Sea Islands community, Brandon wrote, “I think they felt betrayed. They worked this land and built a community as a symbol of Black freedom and that was taken away.” Combining his feelings with those he imagined for the Sea Islands community, Josh added, “The government just teased us. They mocked us by giving us land and then taking it away like it was on a fish hook. The freedmen and women probably felt outraged . . . like the government didn’t care about them.”

Students had many opinions about why the government gave back land to former plantation owners. Josh believed it was to “establish that whites have more power.” Paul thought that the government didn’t think formerly enslaved people “deserved the land that white people originally owned.” Gaby, on the other hand, thought it was because the government wanted “to make money off of it and sell cotton to the North.” Angela agreed, writing that “the U.S. government decided to give former plantation owners back their land because they knew those former owners would produce cotton. These people committed treason but were pardoned and given back their land to boost the economy.”

Indeed, what is often missing in the telling of presidential Reconstruction is that Andrew Johnson was not only thinking about restoring white rule in the South, he was also carrying out the wishes of a section of the industrial and financial elite of the North who preferred a return to business as usual. Several Northern businesses profited immensely from the production of cash crops before the war and their owners hoped the end of the war would signal a shift back to cash crop production in the South. Furthermore, if enslaved people could successfully make a case that the wealth of their former owners should be redistributed to them, what was to prevent the workers of the North from making similar demands on the wealth of Northern capitalists? The titans of Northern industry and finance and their representatives in the government decided that the revolution in the South had to have limits and property rights had to be respected. This meant that freedpeople who had been farming the land, growing crops for their own sustenance, had to be dispossessed. The land was given back to the former slave owners or leased to Northern capitalists hoping to make a buck off the new South.

Although it’s true that many Republicans and business owners would come to reject Johnson’s Reconstruction plan and embrace Black civil and political rights, few were willing to envision Blacks in the south as landowners rather than workers. When Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens proposed redistributing the land of former Confederates, his bill couldn’t even get out of committee. It’s hard to imagine how deeply history might have changed if land distribution was expanded from the Sea Islands to the rest of the South, rather than reversed. When Blacks won the right to vote a few years after the Sea Islands experiment, for the first time in history more than 1,500 Black people were elected to local, state, and federal offices throughout the South. Despite the acquisition of tremendous political power, control of the Southern economy remained in the hands of the white elite who were determined to win back the reins of the government — by violence if necessary. The lack of economic power left Blacks vulnerable. Furthermore, taking land redistribution off the table undermined the potential coalition between freedpeople and land-hungry poor whites who were ultimately swayed by the white elites’ appeal to racism.

While the story of the Sea Islands is a profound tragedy, students could also clearly see the promise in this experiment in Black self-determination. Corina felt it was “inspiring to see how newly freed slaves never gave up. Even though they were constantly made to feel less than, they still fought for their rights and their survival.” Allie wrote that the story of the Sea Islands “shows the will and strength people have to gain freedom. . . . The desire to not just survive but thrive together.” Greta summed it up by saying, “This story is not simply a tragedy because it did not end here. People were freed, they established their own land, schools, homes, government. They came a long way even though they had to continue to fight for their rights.” For Angela, the Sea Islands community “was a symbol of Black freedom. . . . It represented hope.”

For teaching materials related to this article (including handouts, maps, and examples), go to bit.ly/40AcresMaterials.

Adam Sanchez (Contact Me) teaches at Harvest Collegiate High School, a public school in New York City. He is a Rethinking Schools editor and is also editor of the new book Teaching a People’s History of Abolition and the Civil War .

Illustrator Keith Henry Brown’s work can be found at keithhenrybrown.com.

***

Resources for Teaching Reconstruction

The Zinn Education Project (ZEP) Teach Reconstruction campaign offers teaching resources to bring this era to life in the classroom. ZEP, a collaboration between Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, points out that “often the story of this grand experiment in interracial democracy is skipped or rushed through in classrooms across the country. Today — in a moment where activists are struggling to make Black lives matter — every student should probe the relevance of Reconstruction.” Teach Reconstruction “aims to help teachers and schools uncover the hidden, bottom-up history of this era.” You can visit ZEP’s Teach Reconstruction campaign at zinnedproject.org/reconstruction

A few of the teaching resources featured at the site include:

Reconstructing the South: A Role Play

By Bill Bigelow

bit.ly/ReconstructingTheSouth

This role play asks students to imagine themselves as people who were formerly enslaved and to wrestle with a number of issues about what they needed to ensure genuine “freedom”: ownership of land — and what the land would be used for; the fate of Confederate leaders; voting rights; self-defense; and conditions placed on the former Confederate states prior to being allowed to return to the Union. The role play’s premise is that the end of the Civil War presented people in our country with a key turning point, that there existed at this moment an opportunity to create a society with much greater equality and justice. It’s followed by a chapter from the book Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution on what would happen to the land in the South after slavery ended.

Make Reconstruction History Visible

bit.ly/MakeReconstructionHistoryVisible

This mapping project is an opportunity for students and teachers to identify and advocate for recognition of Reconstruction history in their community. This helps students learn about this vital era in U.S. history while also playing an active role in giving visibility to a period that has been hidden — and often misrepresented — for too long. In Make Reconstruction History Visible, students (individually or as a class) identify and document Reconstruction history such as schools, hospitals, election sites, Freedmen’s Bureau offices, Black churches, Black newspapers, Black-owned businesses, prominent individuals, organizations, key events, and more.

When the Impossible Suddenly Became Possible: A Reconstruction Mixer

By Adam Sanchez and Nqobile Mthethwa

bit.ly/Impossible_Possible

This mixer aims to draw out many of Reconstruction’s lessons for students by introducing them to individuals in the various social movements, including the labor movement, women’s rights, and voting rights movements that followed the Civil War and their attempts to build alliances with one another. In the mixer, each student takes on the role of a different person involved in the social movements of the time.

Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution

By the American Social History Project

bit.ly/FreedomsUnfinishedRevolution

Where most high school texts organize chapters on Reconstruction around the policy zigs and zags of Abraham Lincoln, then Andrew Johnson, then the Radical Republicans, et al., Freedom’s Unfinished Revolution focuses on the creativity and determination of people at the bottom. Formerly enslaved people destroyed cotton gins, refused to work in gangs under white overseers, demanded their own land, and in 1867 in South Carolina refused to pay taxes to the white planter-dominated government. Documents from numerous sources — novels, letters, speeches, congressional testimony, newspaper editorials — breathe life into the text and are accompanied by generally provocative discussion questions.