Finding Signs of Hope

A veteran classroom teacher finds inspiration in the everyday work of committed coworkers

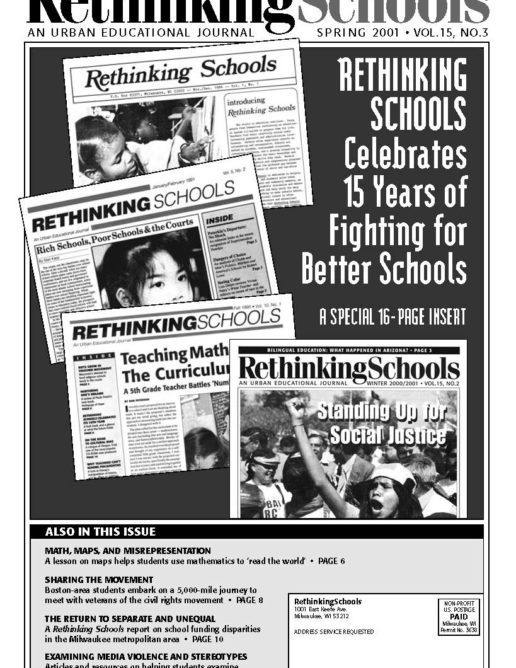

For fifteen years, the voice of Rethinking Schools editors and writers has operated as a collective conscience reminding us that teachers can make a difference in children’s education inside and outside of the classroom. Through examples and exhortations the journal has prodded us to continue our work. Rethinking Schools lays out a framework for social justice education an audacious path of survival for those of us who believe in the rights of all students to a challenging education and demands that we find possibility in the midst of despair. Rethinking Schools begins its second 15 years in the midst of voucher threats, increased testing, and more unequal funding. Still, in my work as High School Language Arts coordinator for Portland Public Schools, I see much to be hopeful about.

For the past two summers Portland high school teachers have worked together in “curriculum camps.” The original intent was to move teachers beyond the thin core of the traditional canon to develop lessons that embedded reading, writing, and speaking work samples within the context of high interest, multicultural literature. Instead of bringing in outside “experts,” we relied on the strengths of the outstanding teachers in our district. As one teacher noted, “What the HS Literacy project makes evident is that working teachers, sharing their best practices, provide the best forum for developing new curriculum.” Through the project, teachers developed curriculum for twenty novels/units of study and brought the voices of African American, Asian American, Latino, and Native American writers into classrooms throughout the district.

Another sliver of hope emerged this year when teachers at a local high school took the school report card designed by Portland Area Rethinking Schools excerpted in Failing Our Kids and decided that their school served the children of the wealthy, but not of the poor. They have undertaken a yearlong investigation into untracking their freshman Language Arts classes. They read research and prepared a position statement for the school community. Using the syllabus of the honor’s course, they created curriculum that challenges all students. In the process of untracking, their department has become a leader in the school’s reform looking at ways to move the entire school to struggle with the achievement and inclusion inequities that have too long been accepted and normalized in the school.

Turning Schools Around

In a high poverty school across town skyrocketing failure rates, high drop out numbers, and unacceptable attendance statistics pushed language arts teachers to ask themselves, “What do we know about learning that will turn this around?” Again, armed with research on best practices in their content area, these teachers are changing their traditional four-year program to bring students back to their classrooms. Instead of English 9, 10, 11, and 12, students will now choose between courses like Shakespeare, Mythology, or “The Other America.”

Naming inequality and speaking out against it is one of the first steps in working for justice. After Pedro Noguera, a professor from Harvard, spoke at an inservice meeting for Portland high school teachers about their role in reducing the achievement gap, teachers met in school groups and talked about how their schools need to change if they want all students to succeed. While not all teachers agreed with Noguera’s message, a number of school communities said it was the most honest discussion they’d had in their school careers.

As Rethinking Schools turns 15, this is what gives me hope: The defiance of teachers who are unwilling to tolerate inequality, the work of teachers seeking out new voices to bring into their classroom, the willingness of teachers to accept that they are creators of change in their school communities. I celebrate those who dare to believe that teachers can create a kitchen-table journal and transform it into a force for educational change.