Expanding Intersectional Queer History in the Elementary Grades

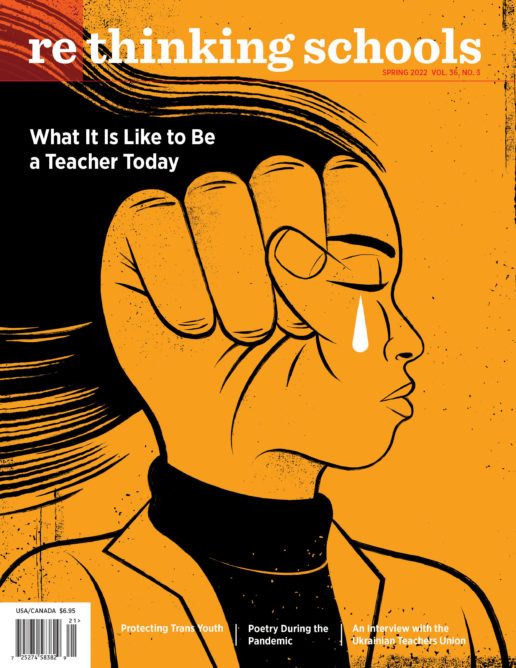

Illustrator: Ebin Lee

My 5th- and 6th-grade students gathered as I drew a tree on chart paper. “This tree represents a person. The branches are all different parts of who this person is. We call these identities. Everyone has many identities that make up who they are.” I labeled some of the branches race, gender, language, ethnicity, religion, and left some blank. “What other identities might be listed on our tree?”

“What’s ethnicity?” Ashley asked. I saw a sketchbook in her lap and wondered how she had brought it to the carpet without my noticing. She was also drawing and labeling a tree — much more detailed than mine.

“Ethnicity means the country or region where someone is from, or the culture they belong to,” I answered. I added the definition to the label. “Over the next few weeks, we will learn about every identity listed here and some that aren’t on the tree yet, and we will learn about how these identities affect each other and work together to make us who we are.”

I posed my question again: “What other identities might we want to add to our tree?”

Mason raised his hand slowly, then put it down. “Mason, what are you thinking about?” I asked.

“What about people who are gay?” Mason asked quietly.

“You’re right, Mason! That is missing from our tree. We call that identity sexual orientation,” I answered as some students giggled. “Sexual orientation just means who you like or love. For example, some men love women, and we call that identity heterosexual. The prefix hetero- means different. However, the prefix homo- means the same, and some men are homosexual, meaning they love men. We also call that gay.”

Asim raised his hand, “My teacher at my other school told us we weren’t allowed to say that word at school.” Other students nodded.

I nodded: “Sometimes gay gets used as a put-down, and that’s inappropriate, but gay as an identity is valid and we need to talk about it in school so we stop using it as a put-down. We talk about all identities here because it’s important to consider what makes someone who they are as we try to understand history and the world as it is today. Look at this tree,” I said as I pointed at my drawing. “If I cover up one of the branches, I will be missing a part of who this person is and how they experience the world.”

I taught the identity tree lesson, which was based on Shane Safir’s work in her daughter’s classroom (see Resources at the end of this article), during the inaugural year of our new grassroots charter school in Greensboro, North Carolina. The school centers restorative justice and allows teachers, students, and community members to co-construct curricula together based on relevant social issues that affect the community and world at large. The school’s student population is racially diverse with students coming from several nearby districts, and the school has a significant population of LGBTQ students and families.

I shared the identity tree lesson with my fellow 5th- and 6th-grade co-teachers during planning that same afternoon and one co-teacher suggested participating in GLSEN’s Ally Week, now called Solidarity Week (see Resources at the end of this article). We decided our participation in Ally Week would become part of a larger unit in the beginning of the year focused on intersectional identity. As we curated resources for this brief unit, we adapted content from GLSEN and the Human Rights Campaign Welcoming Schools program (see Resources).

The activities outlined in this article are my adaptations of content that our team planned and implemented to help 5th- and 6th-grade students create an intersectional awareness of LGBTQ identities. Due to the limited time within Ally Week and our unit on identity, the goal was to lay a foundation for students to understand the ways that intersectional queerness affects the experiences of LGBTQ individuals. With the current increase of anti-trans legislation and now Florida’s Don’t Say Gay bill, it’s imperative for our students to see examples of LGBTQIA+ people in the past, present, and their future.

Introducing Intersectionality

One day after our mid-morning snack break, I wrote the letters LGBTQ on the board, with the letters L, G, B, in green; T in blue; and Q in red. I asked, “Does anyone know what these letters stand for?”

Mason raised his hand. “G is gay,” he responded, “and I think L is for les-bee-ann or something like that.”

“Lesbian,” I corrected, “Yes, and remember that gay is referring to men who love men. What does it mean for someone to be a lesbian?”

Virginia raised her hand. “My aunt is lesbian. She likes women.”

I added the words “gay” and “lesbian” underneath the letters. Nora raised her hand and said, “B is for bisexual. I know because I am bisexual.” She laughed nervously.

“Thank you so much for sharing that with us, Nora,” I watched Nora as she heard my words. Her eyes started to tear up.

“Are you OK?” Mason asked.

“Yeah. It’s just I haven’t told anybody that before, but I like boys and girls,” Nora responded, wiping away a tear.

“You must really trust us to tell the class that you are bisexual. Thank you for sharing who you are with us.” I walked over to the identity tree and continued, “Friends, remember, someone’s sexual orientation is part of who they are, and this is important because it can affect the way they experience the world in the way people treat them. They may get teased or experience discrimination because they are gay, bisexual, or lesbian. If we look only at the tree branch labeled gender or sexual orientation, we aren’t seeing the whole person, and we may treat them differently if they are different from what we’re used to. However, if we look at someone but completely ignore gender or sexuality, we aren’t seeing the full picture of who someone is either, and these are two things that lead to bias and discrimination. We are creating a classroom community in these first weeks of school, and we want everyone to feel safe and welcome here.”

I continued the lesson and pointed out that the words L, G, and B were in green because they were related to sexuality; T was blue because it stood for transgender because people who are transgender identify with a gender other than what they were assigned at birth, and gender really refers to how someone expresses themselves, and Q was in red because queer can refer to gender or sexuality. I left our color-coded letters on the board to refer to throughout Ally Week and the rest of our identity unit. When students would occasionally forget what different letters or words meant, we would refer back to the chart.

In our larger unit on identity, I had started to notice that students were decontextualizing other identities that queer figures had, like their race, socioeconomic status, disability, ethnicity, and language. So I decided we would read the picture book IntersectionAllies: We Make Room for All. Kimberlé Crenshaw writes the foreword of the book, and I note she coined the term “intersectionality,” which we refer to in other units throughout the year. As we visit and revisit this topic, we come to define intersectionality as the ways overlapping marginalized identities can lead to intersectional oppression and also be a source of solidarity and pride. The book introduces several characters with different identities and describes how each character advocates for their friends whether they share identities or not. The end of the book has overviews of each character and their specific identities. This book helps illustrate the ways that thinking about intersectionality can help build solidarity across groups.

After I finished reading the book to the class in our meeting space, I closed the cover and pointed to our identity tree. “What did you notice about the characters in the book? Were there any you identified with or were curious to know more about?”

Asim raised his hand. “I noticed Nia and I think she was referring to the Black Lives Matter protests.”

I opened to Nia’s page. “What identities did Nia have based on the text?”

Asim studied the picture. “She’s Black, and a girl, and she’s brave because she’s standing up to the cops.”

“And she has a cat,” exclaimed Ashley.

“Where would we put these things on our tree?” I asked.

Nora: “Her gender is girl and her race is Black or African American.”

“Do we know for sure that Nia is a girl?” I turned to the Book Notes section of the book. I read aloud “Kimberlé Crenshaw first made up the word intersectionality to describe how the criminal justice system treats Black women and girls like Nia and her mom differently than Black men and white women.”

“So, she is a girl,” Virginia said.

“Yes, and remember, Nia’s identities as a Black girl affect how she experiences the world, and that would be different from a white girl.”

Suddenly Nora jumped up. “Wait a second. I’m Black and white. I’m a girl. I’m bisexual. I’m Muslim. Is that what Kimberlé Crenshaw meant?”

“Sort of,” I took a beat and searched for words. Nora was picking up on how she holds multiple identities at once but I wasn’t quite sure how to answer her question because her understanding of intersectionality was missing how her identities overlapped to create intersecting points of oppression. I knew I needed to explain further, but it didn’t seem appropriate to have students reflect on their own levels of oppression at this point.

“I am going to need to think about this more in order to really answer your question, Nora,” I responded. “I think it’s super important that you are noticing all of these identities that you have. Turn and talk with an elbow partner about some of the identities you share with the characters in the book.” I knew that giving students time to reflect on their identities would help them make connections with the book and the other content we had been discussing in our unit on identity as well as Ally Week, but more information would be needed as we continued to unpack queer identities.

Queer Historical Figures

That evening, I thought a lot about Nora’s question. I decided to introduce a diverse group of historical figures during morning meetings for the rest of Ally Week. Students would read a short biography of one person each morning. Then we would relate the text to our identity tree to connect their queerness back to other identities in order to build our understanding of intersectionality. We started with Pauli Murray.

As I called everyone to the meeting space, I pulled out a photo of Pauli Murray and read a summary I had created about them using various websites.

Virginia stopped me mid-sentence. “Why do you keep saying them, he, or she?”

“Pauli Murray had a broader definition of gender. At some points in their life they identified as a woman and used she/her, and at other points Pauli identified as a man and used he/him. Let’s think about what Pauli’s identity tree may have looked like.” I looked over at the chart again. The class sat in silence for a moment, then Mason suddenly cocked his head to one side.

“What did you notice, Mason?” I asked.

“Pauli was Black and Christian, but I don’t know about their gender.”

I looked back at the summary. “Sometimes the words we use to describe ourselves change over time. We don’t know exactly how Pauli described themself, and we know it shifted throughout their life. Now we might call that gender fluid, non-binary, or genderqueer. These terms didn’t exist when Pauli was alive, but many genderqueer people did. In fact, the word queer itself was considered a huge insult during that time but has since been reclaimed; meaning that LGBTQ people have taken the word that meant something harmful and have adapted it to mean something positive.” Even though oppression is an important part of intersectionality, I also wanted to highlight the way identities are sources of pride and solidarity.

At the same time, I think it is important that students understand what intersectional oppression might look like. I continued: “We could say simply that Pauli was trans, meaning they have a gender identity different from the sex they were assigned at birth. Pauli experienced oppression because they were Black, queer, trans, and assigned female at birth. Even though they were also probably a source of pride and solidarity, Pauli’s Blackness meant they were excluded, their queerness meant they were excluded, their transness meant they were excluded, and their femaleness meant they were excluded. For example, under the Jim Crow laws, Pauli would not have been able to attend school with white students. During this time it was also illegal to wear clothing that didn’t match the gender on your driver’s license; so Pauli likely experienced discrimination because of these things.”

Ashley looked at the photo of Pauli Murray and asked, “Can we put this picture up in the classroom?”

“That’s a great idea,” I told her. “We are going to learn about a different person every day this week. Do you want to be in charge of displaying the photos for us and writing a caption to help us remember what we learned about each person?” I wanted Ashley to continue with this since it was her idea; in addition, even though she was an avid artist, Ashley was a reluctant writer, so I knew this kind of practice would help her gain more confidence.

Ashley nodded. She mounted the photo on construction paper and captioned it “Sometimes the words we use to describe ourselves change over time. Pauli Murray used she, he, and they pronouns.”

Throughout the rest of the week we learned about We’wha, Frida Kahlo, and Bayard Rustin. Ashley hung the photos and added captions that I helped her choose using salient quotes from our reading:

We’wha — Many Native American cultures have more than two genders. We’wha was Zuni and they were Two Spirit, so they had qualities of a man and a woman.

Frida Kahlo — Frida Kahlo was a famous Mexican painter. She was also bisexual, meaning she loved men and women. Frida Kahlo sometimes used her art to express different genders.

Bayard Rustin — Bayard Rustin was a Black gay man and he worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Civil Rights Movement. He even helped him plan the March on Washington.

The captions we used were more about identities. This is mostly due to the limited amount of time we had for this unit and the complicated nature of intersectionality, but we continued to circle back to it throughout the year. I have found that complicated topics are best taught in a recursive manner so that students are able to grapple with them in multiple contexts. Later in the year, for example, we did a unit focusing on Ella Baker’s life, learning about her work as an activist in the Civil Rights Movement as we read the picture book We Who Believe in Freedom: The Life and Times of Ella Baker by Lea Williams. We discussed the ways Baker’s identities as a Black woman influenced her experiences and activism. After reading about the ways she was excluded from leadership in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Mason raised his hand and said, “Wait a minute. Ella Baker is treated bad because she’s a woman and because she’s Black. That isn’t fair.” Realizations like this that are shared with the class community allow us to circle back to revisit intersectionality in new contexts.

Toward an Inclusive Pride Flag

In addition to trying to talk about intersectionality by introducing individual queer activists, I wanted students to see how the Pride movement had grown more inclusive over time. I had recently read a lesson about Philadelphia’s More Color More Pride campaign, where Amber Hikes and other queer activists of color called attention to the ways people of color have been historically and systemically excluded from Pride events (see Resources at the end of this article). In order to further our understanding of intersectional oppression and queerness, as well as pride and solidarity, I wanted students to learn about the significance of the rainbow flag and why it has evolved over time.

When one of my colleagues mentioned the idea of making a pride flag for our class based on a lesson from the Human Rights Campaign Foundation’s Welcoming Schools program (see Resources), I realized we could center intersectional queerness by talking about how Gilbert Baker’s pride flag has been adapted by contemporary activists.

We started by reading the picture book Pride: The Story of Harvey Milk and the Rainbow Flag, which covers some of the history behind the Gay Liberation Movement through the story of Gilbert Baker’s making of the pride flag. However, if left as a stand-alone text, it can leave students thinking that the movement was started by white gay men alone. Sometimes when I know a book will require more context, I read it aloud, end with one to two discussion questions, and know that we will explore a complicated topic more in depth in the coming days.

“Why do you think the pride flag was so important?” I asked as I closed the book.

“Each stripe meant something,” said Virginia.

“Yeah, and it helps people remember to celebrate who they are,” Mason added.

“OK,” I started, “so who do we think the pride flag is for? Why is it used?”

There was a pause. I wondered if my questions were confusing.

“It’s for LGBTQ people,” Nora said.

“I think it’s for everybody,” Virginia countered.

Knowing that this would help us start our discussion of Philadelphia’s pride flag, I said, “We are going to pause here, but I want us to keep thinking about what the pride flag represents and why we have continued using it.”

The next day I read Stonewall: A Building. An Uprising. A Revolution. to the class. This picture book tells the story of the Stonewall Inn through the perspective of the building as it changed over time. The story begins with horses in a barn stall, and then goes through the evolution of the building and its place in Greenwich Village as New York changed over time. The majority of the book focuses on the Stonewall Inn as a place of refuge and resilience for people in LGBTQ communities.

As I closed the book, I allowed the story to sink in before starting a reflection discussion. Virginia broke the silence. “I still don’t understand why the police kept coming back.”

“Because they didn’t like that they were gay,” retorted Asim.

“I wouldn’t let them kick me out,” said Mason.

“If the police didn’t raid the Stonewall Inn, then we wouldn’t have Pride,” Ashley added.

As with Pride, Stonewall also falls short of illustrating the full history of the Stonewall uprising. Based on my students’ discussion, the entire Gay Liberation Movement was getting boiled down to a few police raids at Stonewall. In actuality, protesting the police brutality experienced by LGBTQ+ people had been started by trans women of color many years before Stonewall.

One of my co-teachers came across the video A Trans History: Time Marches Forward and So Do We narrated by Laverne Cox. This video describes how trans women of color started fighting for their rights at Compton’s Cafeteria before the Stonewall Riots and highlights the current ongoing oppression of the trans community. Even in our short unit, I wanted students to see the influence of trans women of color in queer history and understand the ways trans people were purposefully excluded, even erased in the dominant narrative about the origins of pride, yet are incredibly resilient.

I introduced the video by connecting it back to the Stonewall Inn. “Remember, Stonewall was a place for LGBTQ people to gather safely, but sometimes police would kick people out. The video we are about to watch will start with Stonewall, but then show us what happened to lead up to the uprising we know as the Stonewall Riots. This video will also help us make connections to life today.”

During the video, students gasped as they noted that North Carolina was one of the states with anti-trans bills. I was glad they were making connections.

The next afternoon during literacy block I shared “Controversy Flies Over Philadelphia’s New Pride Flag,” an NBC News article about Philadelphia’s new pride flag and their More Color More Pride campaign. I reminded students about our previous learning: “Remember how we read about Gilbert Baker’s pride flag? A group of people in Philadelphia have created a new version of that flag in order to be more inclusive of people of color. This new flag has black and brown stripes at the top. We are going to read this article with our reading partners and then come back together to talk about it.”

After reading about the newer version of the flag, Ashley suggested that we make our own Philadelphia pride flag. We pulled out paints and butcher paper, and Ashley suggested we paint handprints in a line to make the stripes. Mason quickly jumped in and drew guidelines for everyone to paint within. Nora then worked with other classmates and started crafting a letter to the co-directors to ask permission to display our work in the school lobby. A few days later, the students’ request was approved and the flag was displayed in the school lobby along with a description of its history, and it stands as a reminder to students to see and celebrate the intersectional identities in our school community and understand their histories.

Just the Beginning

We continued to circle back to the identity tree and intersectional queerness throughout the year. Black Lives Matter Week of Action has resources on being queer and trans affirming. We talked about Janelle Monáe during our unit on Afrofuturism so that students see Afrofuturism as an example of reimagining the narrative of people of African descent outside of the heteronormativity and cissexism that were introduced and policed through colonization. Afrofuturism and the work of artists like Janelle Monáe imagines a past, present, and future where the brilliance and creativity of Black people thrives. In our unit on immigration, we read poems by undocumented queer immigrants in order to understand how queer immigrants experience additional challenges of acceptance and belonging due to heteronormativity in addition to xenophobia.

Centralizing intersectional queerness makes LGBTQ identities another visible part of the human experience. It helps create a classroom culture where students feel they can celebrate and express all of their identities.

***

Resources

A Trans History: Time Marches Forward and So Do We. The ACLU. 2017. YouTube. www.aclu.org/video/trans-history-time-marches-forward-and-so-do-we

Compton, Julie. 2017. “Controversy Flies Over Philadelphia’s New Pride Flag.” NBC News. June 15.

GLSEN. “Solidarity Week Elementary Educator Guide.” www.glsen.org/programs/solidarity-week.

Human Rights Campaign Foundation Welcoming Schools. www.welcomingschools.org/resources/lessons.

Human Rights Campaign Foundation. “Harvey Milk and the Rainbow Flag Symbols of Us: Identity Capes or Flags.” Welcoming Schools. https://assets2.hrc.org/welcoming-schools/documents/WS_Lesson_Harvey_Milk_Rainbow_Flag_Symbols.pdf

Johnson, C., Council, L. T., Choi, C., & Smith, A. S. 2019. IntersectionAllies: We Make Room for All. Dottir Press.

Safir, Shane. 2016. “Fostering Identity Safety in Your Classroom.” Edutopia. Feb. 19. www.edutopia.org/blog/fostering-identity-safety-in-classroom-shane-safir.

Sanders, Rob. 2018. Pride: The Story of Harvey Milk and the Rainbow Flag. Random House.

Sanders, Rob. 2019. Stonewall: A Building. An Uprising. A Revolution. Random House.

Williams, Lea E. 2017. We Who Believe in Freedom: The Life and Times of Ella Baker. UNC Press Books.