By the editors of Rethinking Schools

Just a week after 14 students and three staff members were murdered at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in February, President Donald Trump predictably — and enthusiastically — endorsed the National Rifle Association’s prescription for school shootings and our nation’s gun violence epidemic: more guns and give them to teachers.

“You give them a little bit of a bonus, so practically for free, you have now made the school into a hardened target,” Trump said, according to The New York Times, giving a nod to the NRA’s mantra that the “Only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

Survivors of the Parkland shooting couldn’t help but find some dark irony in Trump’s stance and that mantra when a couple months later the NRA announced that guns would be banned from both Trump and Vice President Mike Pence’s speeches at their annual convention.

Parkland student Matt Deitsch wrote on Twitter: “Wait wait wait wait wait wait you’re telling me to make the VP safe there aren’t any weapons around but when it comes to children they want guns everywhere? Can someone explain this to me? Because it sounds like the NRA wants to protect people who help them sell guns, not kids.”

Deitsch is right, of course, and his comment exposes an underlying issue in any conversation about gun violence in schools in the United States: This is fundamentally an issue of profits versus the health and security of our young people.

[This editorial is from Rethinking Schools’ summer issue, which was released earlier this month. To read articles from the rest of the issue and to subscribe to the magazine, visit www.rethinkingschools.org]

The arms industry, with political protection from the NRA, is given the “right” to sell weapons without meaningful restrictions at the expense of young people, our schools, and our communities. Gun-related deaths are now the third-leading cause of death for Americans younger than 18, according to a study published last June in Pediatrics.

Trump and the NRA might propose that teachers be armed, but educators have largely rejected the premise as both unsafe and unwise. A Gallup poll conducted shortly after Trump made his comments about teachers and guns found that three out of four opposed the idea nationally and the vast majority felt arming staff members would make schools less safe.

And indeed, stories of students injured by teachers who have accidentally discharged weapons are becoming all too common. Many of them sound like a March incident in Seaside, California, when a high school student was hurt when his teacher accidentally fired a shot into the ceiling and it ricocheted.

Trump and others who initially called for teachers to be armed after Parkland have also been noticeably silent on the matter since teachers in several states went on strike and started storming state capitols in protest.

But there’s much more that we as educators can do — besides dismissing yet one more unsurprisingly bad idea from Trump — to combat gun violence and get guns out of our schools.

One of our roles as teachers is to guide students to examine the roots of an issue. When we talk about the Bill of Rights and the roots of the Second Amendment, we can expose the popular mythology that surrounds it — that this is somehow about individuals resisting government oppression — and lay out its true intent: to defend and deepen white supremacy.

In her book Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz shows that the Second Amendment began in slave patrols and in collective measures by white farmers to steal Indigenous people’s land and then to “defend” themselves from those same people who were unwilling to be victims of that theft.

“While the ‘savage wars’ against Native Nations instituted brutal modes of violence for the U.S. military, and slave patrols seamlessly evolved into modern police forces, both have normalized racialized violence and affinity for firearms in U.S. society,” writes Dunbar-Ortiz.

And there is no shortage of other lessons or examples throughout U.S. history to help students internalize this narrative.

After the Civil War, many Southern states passed laws known as Black Codes that among other things prohibited Blacks from owning or carrying guns.

During the Civil Rights Movement, then-Gov. Ronald Reagan responded to efforts by the Black Panther Party to conduct armed patrols of neighborhoods in Oakland by signing the Mulford Act in 1967, which prohibited the carrying of loaded firearms in public.

And one of the most tangible examples for students might be when, after his home was bombed in 1956, Martin Luther King Jr. applied for a concealed carry permit in Alabama, only to be denied by police because he was deemed “unsuitable.”

Understanding these histories and the evolution of slave patrols into modern police forces can also help students make connections between the Second Amendment and police shootings of unarmed Black and Brown youth. In 2017, 28 children — most of them Black — were shot to death by police.

Many students are already making these and other connections. The Philadelphia Student Union, for example, responded to the Parkland shooting by organizing a March for School Safety that carried several demands. Among them: “Gun control that does not result in targeted policing of Black and Brown bodies.”

Another way that educators can tailor our curriculum to combat gun violence is by getting the NRA out of it, literally.

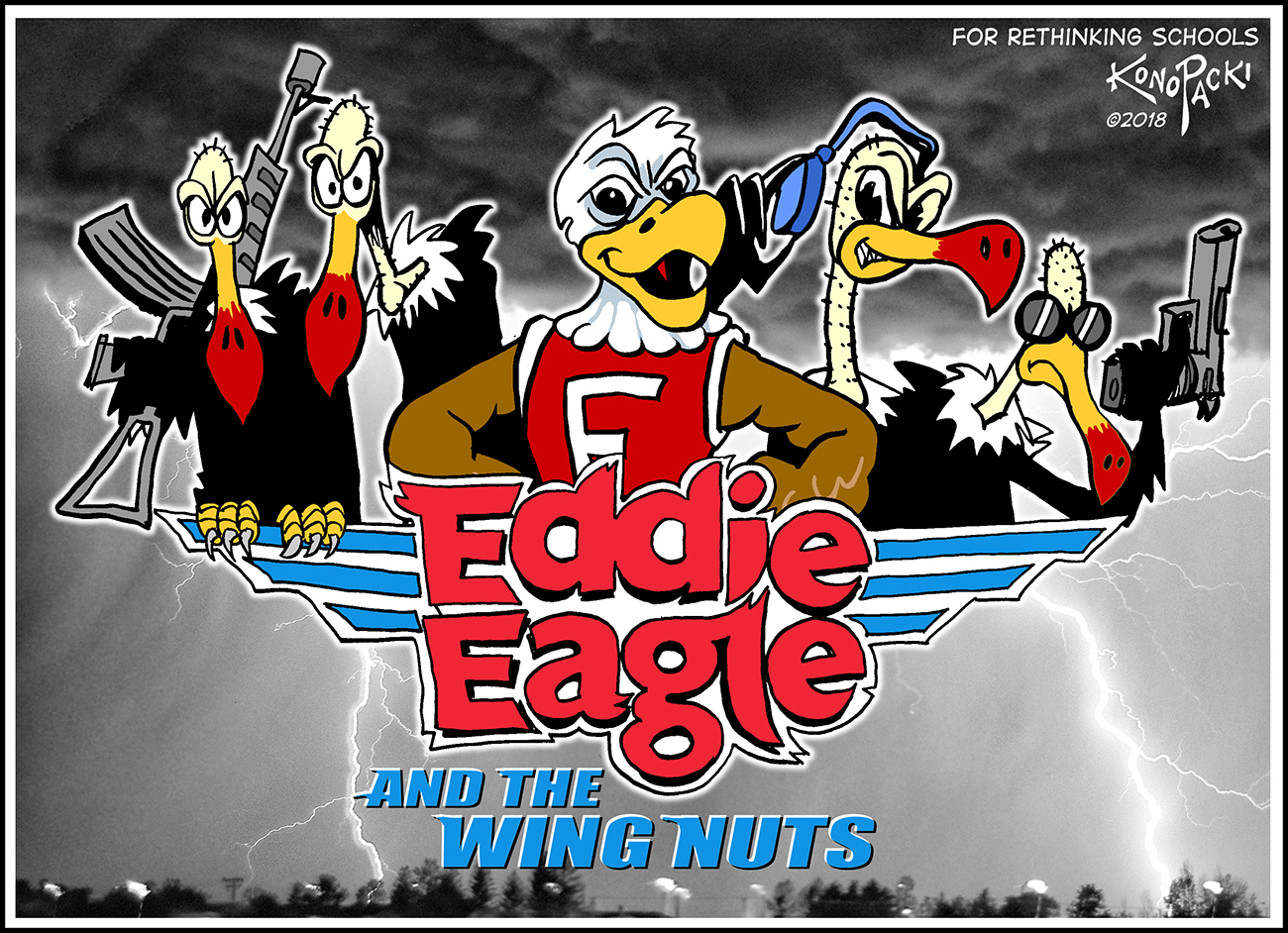

While the NRA protects arms manufacturers and bullies any politician who proposes regulations on firearms, they simultaneously pretend to combat gun violence by pushing a curriculum into schools across the nation called the Eddie Eagle GunSafe Program.

The curriculum, which features cartoon character Eddie Eagle, is designed for pre-K through 4th grade and has been officially endorsed by several states including Oregon, Florida, Alaska, Nevada, Georgia, and Idaho, and like the Second Amendment, it too can be exposed by looking at its roots.

The program was started in 1988 by gun lobbyist Marion Hammer (responsible for “stand your ground” legislation) as a measure “to deter lawmakers from passing child access prevention (CAP) laws, which criminalize keeping firearms easily within reach of children,” according to journalist Isha Aran, who wrote about the issue for Splinter.

Aran notes that Hammer used the program to flip the script — instead of adults being punished for keeping guns around children, children should simply not touch guns, “effectively shifting the responsibility of not getting shot by a gun an adult left lying around to kids.”

As educators, we must lead the charge against programs like Eddie Eagle that normalize guns and gun violence and we should develop curriculum that looks like Linda Christensen’s important lesson “Trayvon Martin and My Students” that examines the killing of Martin and contrasts comments by President Barack Obama and Cornel West to help students develop their own narratives and critical analysis of the intersections of race and gun violence.

Another example is Renée Watson’s powerful lesson “Happening Yesterday, Happened Tomorrow” that teaches students about the ongoing murders of Black men by having students explore and dissect the poems “Night, for Henry Dumas” by Aracelis Girmay and “Forty-One Bullets Off-Broadway” by Willie Perdomo and then write their own poems about police shootings.

And as educators we can also get guns out of our schools by teaching critically about wars and the vast amounts of money we spend as a nation on weapons and killing, and by literally demilitarizing them — advocating that our schools no longer house any JROTC programs.

In an article for Rethinking Schools in 2014, teacher Sylvia McGauley debunked the myth that JROTC is about education and leadership and argued that “by housing recruiters and JROTC in public schools and offering them carte blanche privileges, we provide them a cloak of legitimacy.”

“Militarism was one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s ‘giant triplets’ of societal destruction (along with racism and extreme materialism), yet today it appears as a legitimate component of the educational system — most often at underfunded schools,” McGauley wrote.

It is also essential that as teachers we nurture the activism we’ve seen from students surrounding our country’s gun violence epidemic. Our classrooms can be sites of reflection and spaces that encourage student action.

These are just a few of the steps that we can take to combat gun violence and support students from Ferguson to Parkland who are asking for something fairly simple: For us to care whether they live or die.

Read more and subscribe at www.rethinkingschools.org

Illustration credits: Mike Konopacki