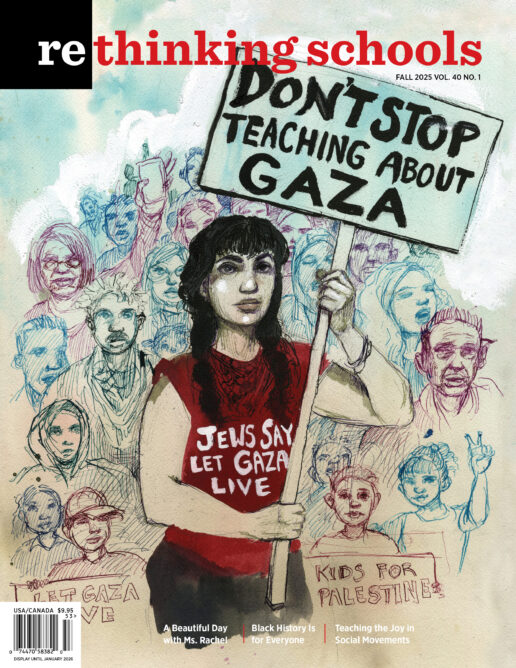

Snapshots of Joy

Using Photo Analysis to Challenge Dominant Narratives

“I thought Martin Luther King Jr. woke up every day and was like ‘fight, fight, fight’ and went to bed and did it all over again. In school, I never learned about his humanity and the person he was outside of organizing,” Arianna, a high school student organizer, exclaimed. Soft murmurs of “yeah!” echoed around her from the other student organizers in the group — an affirmation that her sentiment resonated. She pointed to one of the photos taped to the wall: “But here, he’s eating pizza. In this one, he’s riding a bike wearing a suit. I love pizza, and I ride my bike!” We could see the other student organizers’ eyes widen as they made connections between their experiences and the photos of Black organizers and artists displayed on the library walls.

“What pictures have you seen of Martin Luther King Jr. in school?” Karen inquired.

“Well, I’ve mostly seen the picture of him waving at the March on Washington or giving the ‘I Have a Dream’ speech. That’s all I got,” Lattisha noted. The group nodded in agreement, struggling to recall other photos.

This is what the beginning of a conversation with high school organizers sounded like on the third floor of the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington, D.C. Over the course of 10 months, we co-facilitated a youth organizing fellowship in Washington, D.C., with a focus on racial justice. The program was sponsored by the Equity Lab, a D.C.-based nonprofit that hosts fellowship programs to support individuals and institutions in tackling racism and injustice. The fellows were high school students in 10th to 12th grade who resided in D.C. and had an interest in completing a social action project in their community.

After completing an application and participating in a brief interview about their interest in the fellowship, 15 fellows were selected to form the cohort. At the start of the fellowship, fellows identified a key social justice issue they wanted to address and began developing a social action project. They spent the year researching their chosen issue, deepening their understanding of social change work, and developing a plan to disrupt injustice in their community. They discussed topics like identity, storytelling, power mapping, and the importance of cultivating joy and wellness practices. Fellows’ projects ranged from encouraging schools to divest in policing and invest in mental health, curbing gun violence, expanding access to social justice curriculum and teaching the truth, and combating discrimination in blood donation against the LGBTQIA+ community.

Images tell stories. The photographs we often see depicted in corporate textbooks paint a one-dimensional story about Black humanity. Mrs. Rosa Parks sitting on a bus. Enslaved people picking cotton. Black Panthers holding guns. Void of nuance and context, these images promote a particular narrative and leave out the stories of Mrs. Parks’ lifelong organizing, how enslaved people resisted, and how Black Panthers protected themselves from a corrupt government destined to squash Black power by any means necessary. Or, how the Black Panthers also sponsored free breakfast programs, health clinics, and a freedom school. This only scratches the surface of what gets left out.

To give students a tangible example of what these different stories look like in history, we developed a lesson that focused on photo analysis to challenge dominant narratives. Students explored photographs of Black organizers and activists — leaders who have shaped justice movements but whose stories are often marginalized or misunderstood.

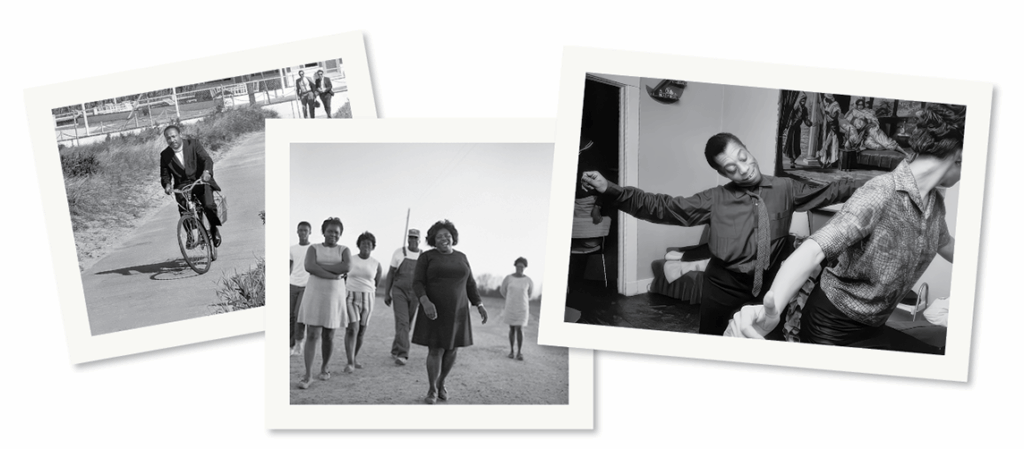

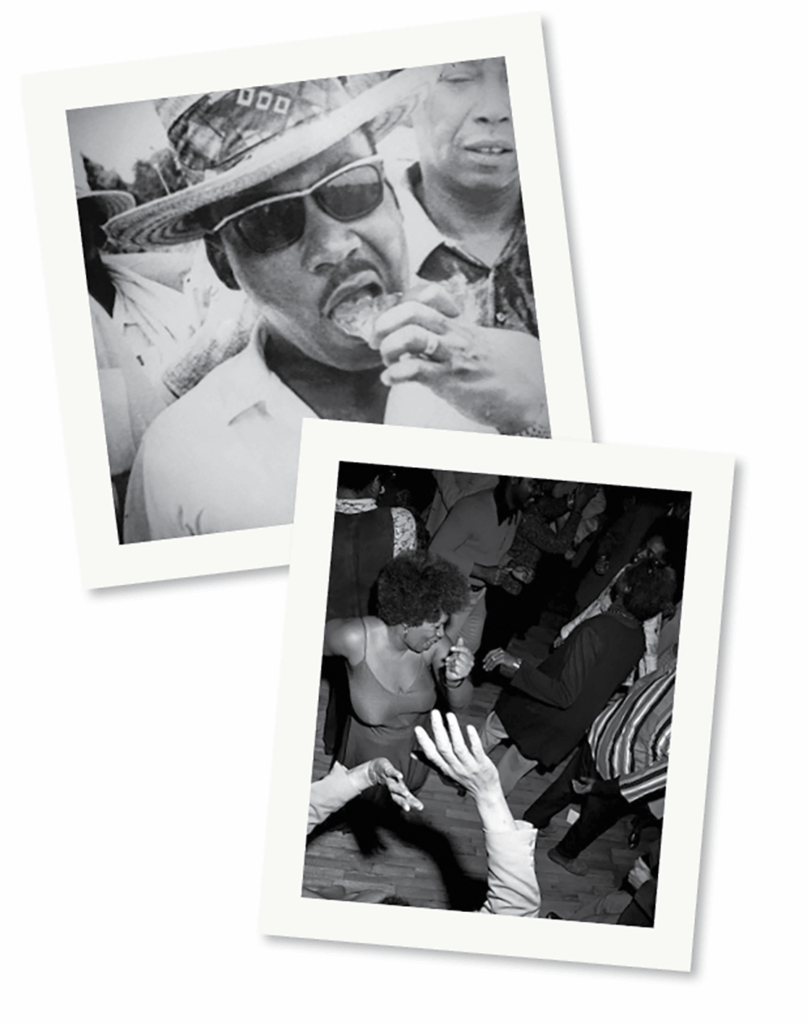

We started by placing printout photos of Black leaders around the room — Martin Luther King Jr. riding a bike, Fannie Lou Hamer laughing with her family, James Baldwin dancing, Bayard Rustin playing a guitar, Rosa Parks on her yoga mat, Toni Morrison on the dance floor, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X laughing together, and more. We placed a sticky note covering the name of the person in the photo, so students could guess who they were as part of their exploration. In a gallery exhibit format, we invited students to move around the room to engage with the photos. In essence, we tried to curate a joy-filled exhibit.

Karen read aloud the reflection questions on the screen: “What do you see? Do you know who the person is in the photo? How does what you see connect to what you already know? How do these images extend your understanding of the people in them? How are you challenged by what you see? Have you seen any of these photos before? If so, where? What kind of story does the photo tell?” We asked students to pick just two questions to start, and then let the conversations flow from there.

Slowly, students got up from their seats and looked at the different pictures hanging around the room. There was a hesitancy about where to start the gallery exhibit, but soon we began to hear whispers as students moved around the room: “Do you know who that is?” or “I feel like I recognize them, but I can’t remember their name.”

Karen stopped with one group as they examined the color picture of Rosa Parks practicing yoga closely. “Whoa, this picture is in color and she is doing yoga!” Karen nudged them forward to lift the Post-it and see who was in the picture and watched their eyes go wide. Charles turned to his partner. “Rosa Parks took time to do yoga? My mom goes to yoga class,” he said, and his partner responded in awe. “I have never seen a color picture of her, I only think of her sitting on the bus.” Cierra overheard the conversation and chimed in. “My favorite story about Rosa Parks is how, in an interview, her nieces and nephews described their ‘Auntie Rosa’ showing up to their house in her yoga pants.” We all giggled.

“I want to go back to the color photo thing for a minute,” Michelle said. “We see so many pictures in black and white, and it makes it seem like so long ago, but when we see them in color, it actually wasn’t all that long ago. My parents were alive during that time, so it can’t be that long ago!”

Soon, the room grew louder with excitement and was filled with their “aha” moments.

“Wait, MLK eats pizza; I eat pizza.”

“Hold up, Thurgood Marshall laughs, I didn’t think he ever cracked a smile.”

“Look at James Baldwin laughing with his whole body.”

“Wow, I’ve never seen Fannie Lou Hamer with her family before.”

“Is that MLK and Malcolm X laughing together? They always put them against each other in our discussions in school.”

Eager students moved around the room, testing each other on who was in the picture and exclaiming their surprise as the iconic civil rights leaders known only to them in black-and-white photos in textbooks became human, sharing the same interests and connections as them. They also saw photographs of the leaders with their families and friends, as well as with other activists and organizers — dancing, laughing, talking, hugging, and shaking hands.

As the mood shifted from awe to reflection, Cierra reminded students of the initial prompts we’d projected: What do you notice in these images, and how do they connect to what you already know? How do these photos deepen or challenge your understanding of the people and stories they represent? Have you seen any of these images before, and if so, where and in what context?

“I leave history class every day angry, but seeing these pictures felt like a deep breath,” reflected Michelle. “I always see my community in pain or experiencing trauma in my history textbooks. Those stories are heavy.”

“What about all of the other people who do everyday things and express everyday joy?” wondered Charlette. “We don’t see their pictures in our textbooks, either.”

Michelle and Charlette’s reflections offered us pause. Photos evoke emotions. The photos we show in our class of who is depicted, and who is not, matter.

“Why do you think these pictures are not typically included in the story that’s usually told about the Civil Rights Movement?” Cierra asked.

“I think textbooks don’t want us to relate to these leaders, so we don’t think we can be them,” Arianna said.

“They try to tell us stories about how the only way to fight for change is not to have a life. But these photos show we can have fun with friends, and make a change,” Simone said.

“Yeah, they’re only known by the outcome of their organizing, but not how they got there and who they were outside of their organizing. The stories leave out all of the other people, like their families and friends, and that they had full lives inside and outside of organizing. Textbooks make it seem like this hero comes out of nowhere and saves the day,” Charles described.

“Yes! Movements for justice have always been collectives of everyday people like you and me. How do these photos make you feel?” Karen asked.

“Powerful,” Lattisha exclaimed.

“Free,” Charlette said.

“That I can have fun and be a normal person, and also fight for justice. It’s not an either/or, it’s a both/and,” Michelle stated.

“That the leaders I learn about in history are like you and me,” Arianna said. “We shouldn’t only learn about what they did, but who they are. It makes them human, not on a pedestal.”

“Yeah, and now I know not only more about these leaders, but about the other people in the cohort. Like, I now know Charles likes to ride his bike all over the city,” Camila said. More laughter filled the room.

“Why do you think we wanted to do this activity?” Cierra asked.

“Well, I think so we could see that even when we’re doing our social action projects, we still have to connect with each other and ourselves. Like, we can’t just organize all the time because that’s not sustainable. We need hobbies and friends,” Charles said.

“Yeah, these photos give us models of how we can still enjoy the things that bring us joy, and organize around the things we are passionate about,” Michelle said.

These pictures and the collective discussion that came with the activity, allow us to see the iconic leaders as full humans, laughing, eating, engaging in hobbies, and enjoying life with friends. We don’t operate in isolation, and we don’t survive without rest. It is in the power of community that people gather the strength and love to keep fighting for the humanity of all people. It is in the joyful resistance that students of today can find connections and encouragement from the leaders who came before them.

The photo analysis served as the foundation for youth organizers to consider the social justice issue they had chosen for their social action project through the lens of storytelling. After this exploration, they spent the remainder of the fellowship drafting and refining a proposal that outlined the dominant narrative about their issue, who was spreading it, the counter-narrative they’d like to propose, and what specific actions they would take to change the narrative. In this, they also went through a power mapping exercise to identify who their audience was and what message they could use to influence them. They also mapped out collaborators and an advisory board, as well as outlined a budget to garner the necessary resources for their project.

This is not just a history lesson. It’s a storytelling intervention. One-dimensional stories trap people in a distant past, making their lives, their acts of resistance seem unreachable in the present.

History shouldn’t be about just looking back — it should help us move forward. By paying attention to the stories we tell and the ones we choose to uplift, we can start telling a fuller, more honest, and more hopeful story of who we are and who we want to become. Oppression thrives on dehumanization. We need humanizing stories to be reminded that wellness and care are not fluffy things, but an integral part of how we teach, learn, and organize. We need stories of everyday, ordinary people who worked in service of justice who found joy in resistance. We have to be well to resist, and most importantly, to dream and organize for the society we deserve.