By Bob Peterson

During my three decades of teaching elementary school I was regularly impressed with how much my students knew about what was happening in the world, and even more impressed by their desire to learn more.

Yes, eyebrows were raised, and at times, parents called principals questioning why my students were discussing certain topics. Sometimes other teachers wondered why my students would volunteer to miss recess to organize a Stop Child Labor action or why the Kids Against the War club would pass out black arm bands to classmates every Friday.

The concern was that “these children are too young to discuss these issues.”

My response, “Really? Do you know what our students’ lives are like?”

One year when one my student’s cousins was murdered, we spent time talking about gun violence and studying gun ownership and homicide statistics during math time. At one point, I asked my 10-year-old students how many had ever held a handgun. More than half the class raised their hands, most of the boys. Being a skeptic who had early in my teaching career learned that 10-year-olds had a propensity to exaggerate, I pressed my students to describe the gun and who owned it. I was stunned. Many of the students not only reeled off the name of the person, but also knew the name of the particular handgun.

“Too young” to discuss things that directly effect their lives? I disagree. Despite parents’ best attempts to shield their children from the frightful and worsening problems that surround us, we are rarely successful.

The massacre of 17 teenagers and teachers at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, is only the most recent tragedy that challenges parents and educators alike.

Should we try to shield young children? If not, how do we talk with them about such horrific events?

An editorial in last summer’s edition of Rethinking Schools addressed this issue:

Young children live in the world, just like we do. They listen to snippets of news reports on the radio; they catch clips of news broadcasts on the television; they hear things from their siblings, parents, and classmates. They watch movies and play video games that encode social tensions and global conflicts. And most importantly, in this time of intense political upheaval, they feel the stress and anger that adults around them are feeling. For many children, poverty, racism, and anti-immigrant hysteria have a daily impact on their lives. When we choose not to deal with these issues explicitly and sensitively, we effectively leave children alone with their misunderstandings and fears.

In my years of teaching 5th grade I have often heard my adult friends make comments that indicate how out of touch they are with young children. Some adults significantly underestimate how aware children are of what’s going on around them and in the world. Others underestimate how capable young children are of having their own opinions about issues that adults would sometimes rather ignore.

One reason I stayed teaching 10- and 11-year-olds for so long was that I always appreciated their seemingly innate sense of justice — or being “fair,” in 5th-grade vernacular.

If educators and parents fail to talk with children about serious, at times controversial, issues — in developmentally appropriate ways — we do them a great disservice. When school superintendents permit middle and high school students to participate in walk outs, like those on March 14, but restrict activities of elementary school students, they also do young children a disservice.

One thing is clear: No matter how hard we try to prevent even the youngest children from learning about the horrors of modern day life, we will fail.

The upcoming March for Our Lives on March 24 and the National Day of Action Against Gun Violence in Schools on April 20th offer two opportunities talk to and involve children in collective civic action that helps them voice their concerns for themselves and others and absorb the hopefulness and power of people working together.

Early childhood educator Nancy Carlsson-Paige offers advice for discussing these upcoming marches with even very young children. Carlsson-Paige writes:

Young children see the world in concrete terms, and they need to have a sense of safety and security. We can emphasize to them that we are marching on this day to keep them and all children safe. Seeing all the people who are marching for the same thing can feel very empowering to a child. She can begin to feel the strength and inspiration that comes from social action.

Carlsson-Paige also suggests: “One of the best means [young children] have for making sense of what they have heard is through pretend play. We can encourage and support children’s play, and we can watch carefully for signs of what any given child might be expressing as their play.” For guidelines on talking to children about violence she suggests Diane Levin’s article “When the World Is a Dangerous Place: Caring for Children in Violent Times.”

As the Rethinking Schools editorial explained, educators and parents should:

Use discretion about the resources we show to children; certain pictures, videos, and stories can clearly be too graphic and too disturbing. It’s up to teachers to know their students and make judgments about how much is too much. It’s also up to teachers to inform and involve parents in this process, without allowing individual parents to dictate what should be taught in school based on their own biases or prejudices. This is a delicate balance. Teachers have used homework assignments in which students ask parents what they think of some of these issues as a way to inform and connect with parents about the curriculum and to encourage multiple perspectives on such topics. The more we, as teachers, build strong ties to our families and communities — and reach out to and collaborate with colleagues — the more able we are to provide our students with a safe, respectful environment to tackle these challenging subjects.

A key goal is to cultivate empathy — both cognitive and emotional — for people who are different from those who we are familiar with. Writer Alfie Kohn encourages educators to help children see themselves in widening circles of empathy that extend beyond self, beyond country, to all humanity.

The Rethinking Schools editorial concludes:

Today, that is more important than ever. In the time of Trump, we are told that America should come first, implying that the lives of U.S. citizens are more valuable than the lives of others. We are told that we should want to build walls and enforce immigration bans to block off people who are not like us. And if we lose sight of empathy, we can end up feeling like … there is no hope for humans, that there is no way back from this dark place we find ourselves in. We owe it to our students, perhaps especially the youngest among them, to resurrect the culture of empathy. We do this by listening to their concerns, trying our best to respond to their questions with respect and compassion, and teaching them to push for a world where everyone’s life is valued.

Hundreds of thousands of us will be doing just that on March 24 and April 20.

Bob Peterson (bob.e.peterson@gmail.com) is a founder of Rethinking Schools and former president of the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association. He taught 5th grade in Milwaukee Public Schools for 30 years.

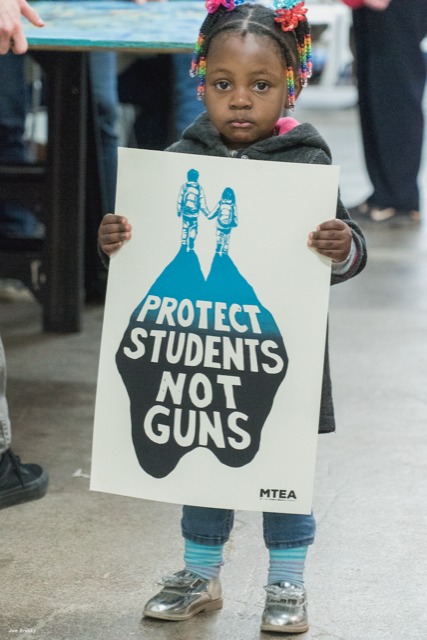

Photo Credit: Joe Brusky

Caption: Daisy was one of the youngest helpers at the Milwaukee Teachers’ Education Association’s art build to create signs for the March for Our Lives.