Resources for Explaining the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program to Elementary School Students

“It just kind of sucks. I mean, going to college and getting financial aid are difficult. And I’m having a lot of trouble finding jobs. I’ve been here basically my whole life. And Yahaira was born here, so she won’t have these same problems. I just don’t know what I’m supposed to do with my life now that I’ve graduated from high school.”

“Yikes,” I said, shaking my head. I didn’t know what to say to Andrés, the 19-year-old brother of my 3rd-grade student, Yahaira. He was helping me chaperone a field trip to the Oakland Museum of Children’s Art and we were sitting on a bench watching the 8- and 9-year-olds chatter away while they ate their lunches in the courtyard.

I was at a loss for words. I couldn’t tell him I knew how he felt. I couldn’t even imagine.

It wasn’t just him, of course. About half of my 3rd graders in 2009 — those who had immigrated to the United States with their parents and were undocumented — would find themselves in the same situation once they finished high school. And as teachers we were motivating them to be readers, to be writers, to be scientists, to reach for their goals, to reach for the stars — all so that they could confront this same cold reality once they tossed their graduation caps in the air. No real access to college. No jobs. Sometimes even a driver’s license was out of reach. Getting pulled over for running a stop sign could mean deportation to a country most didn’t even remember.

But when DACA passed in 2012, there was hope for young people like Andrés and the students in my 3rd-grade class. Since 2012, 78 percent of the 1.1 million eligible young people in the U.S. — almost 800,000 — have applied for and been granted protections under DACA, allowing them to study and work legally in the United States. My former 3rd graders are 17- and 18-years-old now, old enough to have applied for DACA but not old enough to have truly started reaping its benefits.

Those students are just some of the 800,000 reasons to be heartbroken about the Trump administration’s announcement yesterday to rescind DACA. But as educators, if we stopped teaching every time the political reality was heartbreaking, if we stopped coming up with creative lesson plans every time Trump and his racist administration did something that was, well, racist, we would never teach.

It’s time to start teaching our students about immigration, about deportation, and about DACA — now.

Teaching DACA Now

As teachers, we may be reeling personally from this week’s announcement about DACA, but we also need to figure out how to process the news and explain it to our students — and we need to do it right away. What is happening with DACA and with undocumented immigrants in general affects them all, with varying degrees of intensity. And our students deserve to be a part of this national conversation.

So here are some resources I’ve put together to start teaching DACA and the DACA repeal in elementary school classrooms. These are tailored toward upper elementary classrooms — 4th and 5th graders — but could be adjusted down to lower elementary or up to middle school.

Children’s Picture Books About Documentation and Deportation

In order to understand what’s at stake with DACA, students first need to grasp what it means to live in the United States without documentation and how this limits a person’s opportunities. They also need to understand what deportation is and how it can tear families apart. If you teach in a context where many of your students have direct experiences with immigration and deportation, try to create space for them to share their fears and their own knowledge safely. “Qué es Deportar?” by Sandra Osorio that was published in Rethinking Schools is a valuable article that shows how a teacher used book groups and discussions to make space for tough conversations and really listen to her students. Remember, especially in this political climate, to never press students to share information about themselves and their families that they feel uncomfortable sharing or that isn’t safe to share in your school community.

Whether or not your students have background knowledge about documentation, citizenship, and deportation, sharing and discussing picture books is a great place to begin. Unfortunately, there aren’t a ton of children’s books out there that tackle these issues head on.

Here are a few suggestions:

From North to South / Del Norte al Sur by René Colato Laínez (Children’s Book Press, 2013). José travels to Tijuana to visit his mother who was deported in a factory raid. At the shelter where she is staying, José meets other women and children who have been deported and separated from their families. This is one of very few books written from the perspective of a child separated from a parent because of deportation.

Hannah Is My Name by Belle Yang (Candlewick, 2007). After immigrating from Taiwan to San Francisco, Hannah’s parents have to struggle to make ends meet by working illegally while waiting for their green cards to come. Her mother is fired from a factory job for not having papers, her father has to hide from immigration raids at the hotel he works at, and her friend in a similar situation is deported. This is an unusually realistic look at the struggles of working without documentation, and also a reminder that not only Latinxs are affected by DACA.

Super Cilantro Girl / La Superniña del Cilantro by Juan Felipe Herrera (Children’s Book Press, 2003). Always a favorite with kids for its comic-book-like style, Super Cilantro Girl relates the story of Esmeralda, whose mother is temporarily detained at the border. In her dream, Esmeralda turns into a giant green superhero, flies to the border, saves her mother from the grim detention center, and then makes green bushes of cilantro grow all over the border — erasing the fences, walls, and barbed wire.

A caution with all of these books — none of them is perfect, and all of them tend to try to smooth things out at the end by manufacturing the types of happy endings that not all families get in real life. José’s mother will be able to come home, Hannah’s family gets their green cards, Esmeralda’s mother was never really in danger to begin with because she’s actually a citizen. Make sure that, in your discussions with students, these happy endings don’t end up obscuring real and more painful realities.

Of course, picture books are only one type of text to use with students. Poems foster rich discussions with all ages of elementary schools students, and upper elementary students can particularly benefit from engaging with short stories and chapter books about immigration. We’d love to hear what resources you’re using with your own students to bring these issues into your classroom (email me at grace@rethinkingschools.org).

Videos and Infographics about DACA

Once students can grasp the difficulties that undocumented people face in the United States — trouble finding jobs, getting drivers licenses, getting into and paying for college, the threat of deportation, the fear of being separated from their families — they have a good basis to understand what DACA is and why it’s important. There are numerous short videos on YouTube that explain DACA, often using DACA recipients’ own words to do so. Here are two that you could start with:

“DACA, Explained”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UzYDqQDNFzc

[wpvideo Q4QclEfD]

This video, especially the first two minutes, accurately explains what DACA is and why it’s important. The second half of the video goes a little bit more in depth about why DACA is being challenged now, which may or may not be appropriate for some students given their age and the extent of their understanding of the U.S. political landscape.

“What Dreamers Gained from DACA, and Stand to Lose”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=65GThGSvVOI

[wpvideo gg27FFuQ]

In this short video, DACA recipients explain what DACA has done for them and their fears about the future.

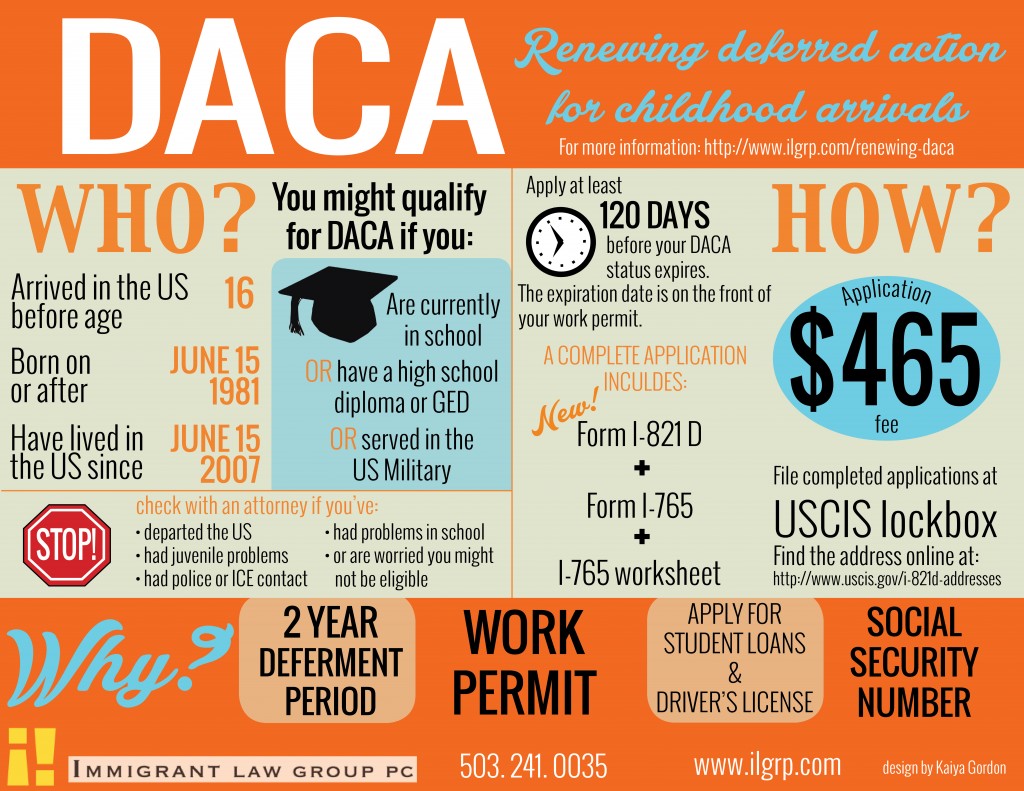

Another tool to share with students are infographics about DACA, which are easy to project on the board and analyze and discuss as a class.

This infographic (below) explains the basics of applying for DACA — who qualified, how much it cost, and what some of the benefits have been.

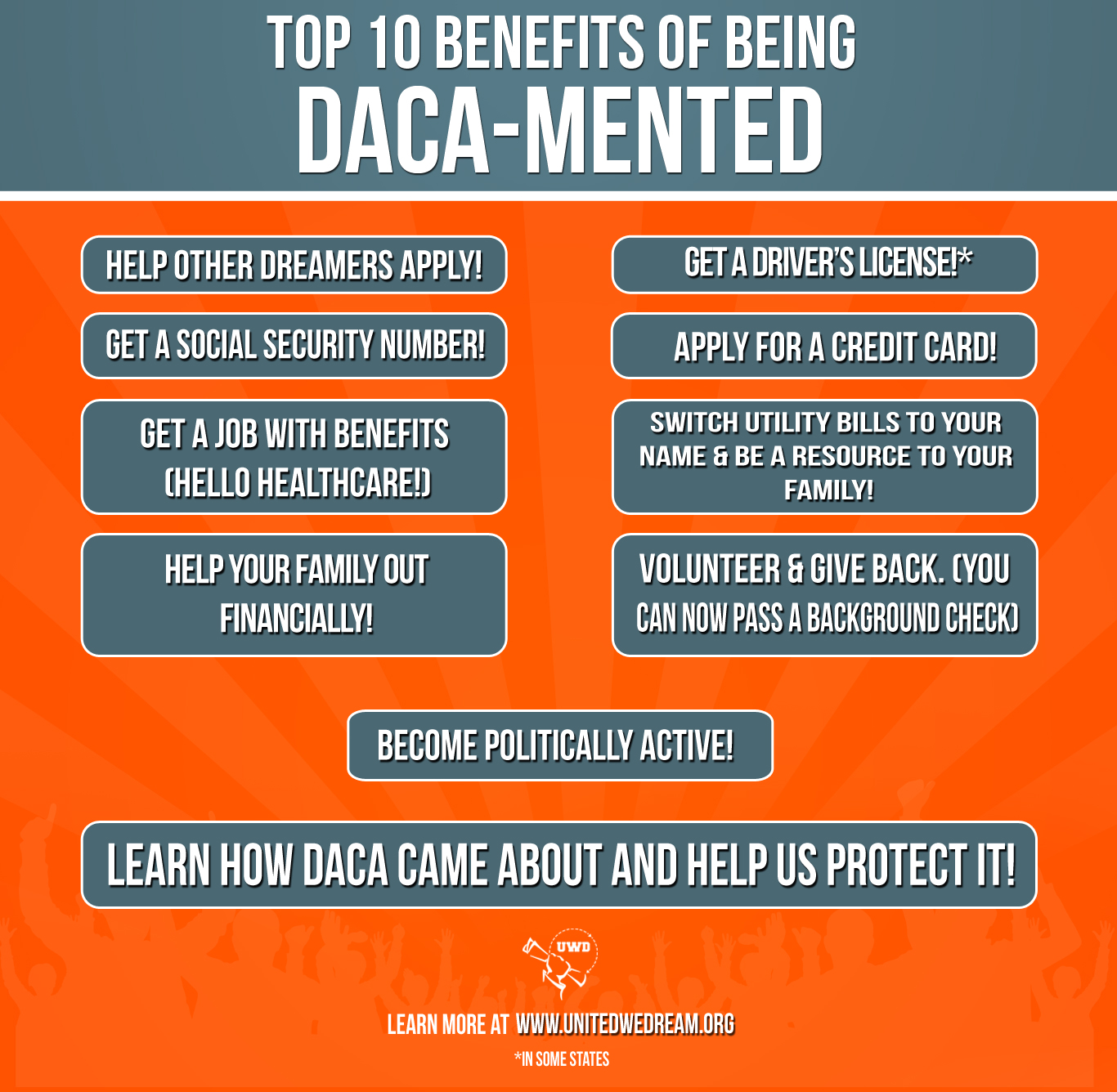

This infographic (below) also lists some benefits to applying to DACA. You can talk with students about what it would mean to them to have or not have the opportunity to do these things as they get older.

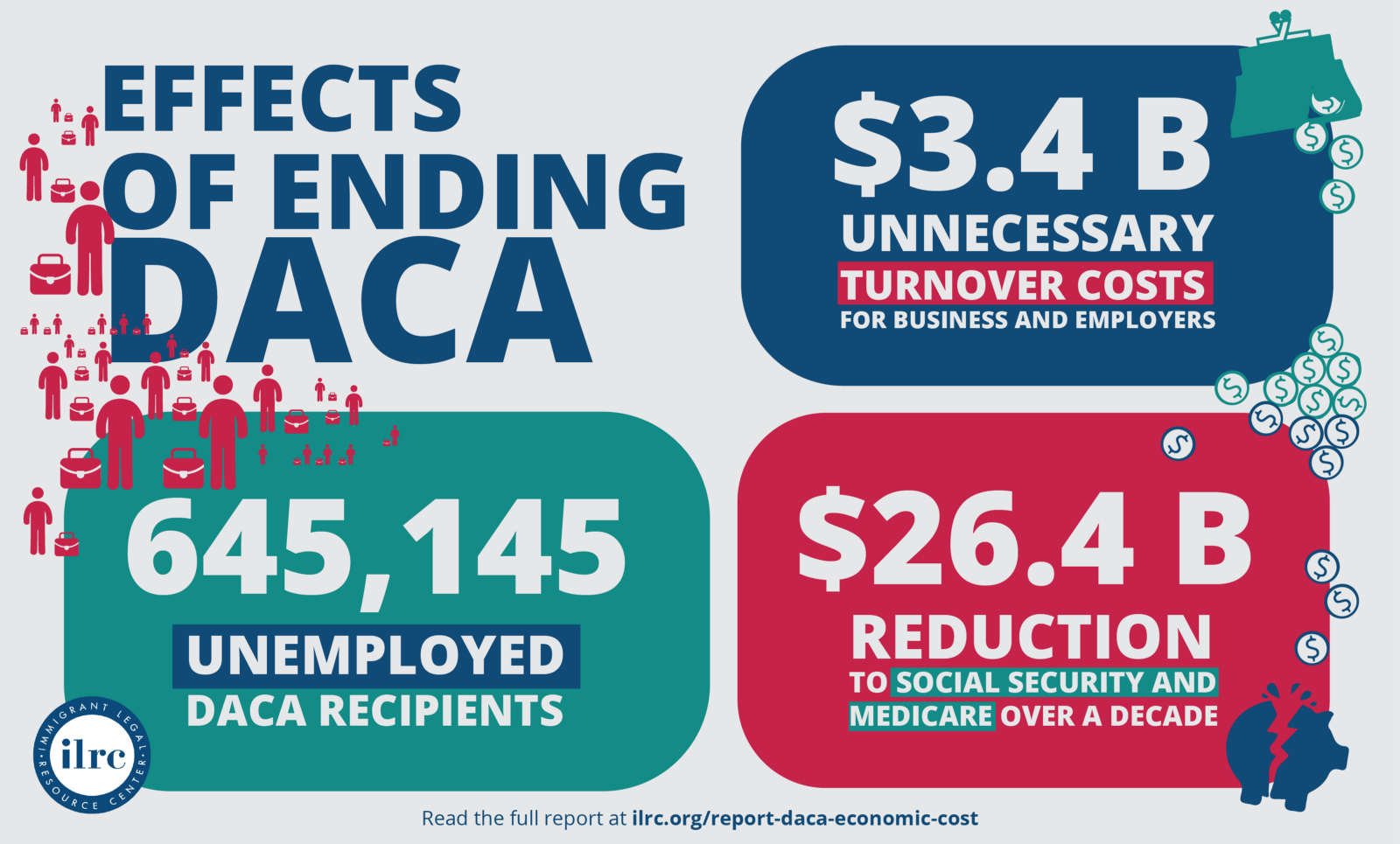

This infographic looks at some of the economic effects of getting rid of DACA. Obviously, these large numbers are abstract, so it would make more sense to share them with older students.

In the days and weeks to come, lots of new online resources will become available, so these videos and infographics are just a small place to start.

Taking Action

If your students want to do something concrete to support DACA recipients, there are a lot of lists right now (like this one and this one) of actions to take. Our students can write letters to their representatives and prompt their parents to do the same. They can raise money for national or local organizations that support DACA recipients, including some that are raising funds right now to help people whose permits will lapse within the next six months re-apply before October 5th. Students (especially older students) can become members of groups and movements like Movimiento Cosecha and United We Dream, and those who will be eligible to vote in 2018 need to make it abundantly clear to their senators and representatives that what they do right now about DACA will matter when elections roll around. But even kids who are too young to vote can directly effect elections through speaking out, writing, and organizing.

Students who are attending protests and community events about DACA can share their experiences, and the class can analyze videos and newspaper stories about demonstrations and community organizing to get a better sense of what is happening with mobilization around DACA right now. Guest presenters are a great way of exploring these issues as well — including student organizers, immigration lawyers, and family and community members. Kids of all ages can also use what they learn to teach their families and school communities about DACA. After studying infographics, they can make their own to display online or in the school hallways. They can hold info sessions about DACA for other classes in the school or for the larger community.

Our students need to know that the fate of DACA and DACA recipients isn’t set in stone. We need to push hard to get legislation passed before March 5, 2018 — and our students need to know that they can make a difference.

One last thought. As teachers, we need to teach about DACA — why it’s important and why we have to fight for DACA recipients right now. But we need to be careful not to limit our conversations about immigration to DACA only. There are many, many undocumented immigrants in this country who all deserve to live with dignity, and most of them have never been eligible for DACA. If we manage to protect DACA recipients now, it is not an end to this fight — it’s only a beginning. We will do our students a huge disservice if this is the only time that we talk to them about immigration.

Photo credit: Gili Getz.

Grace Cornell Gonzales has worked as a bilingual elementary school teacher in Oakland, San Francisco, and Guatemala City. She now lives in Seattle, Washington, co-edited Rethinking Bilingual Education, and is the submissions editor for Rethinking Schools.