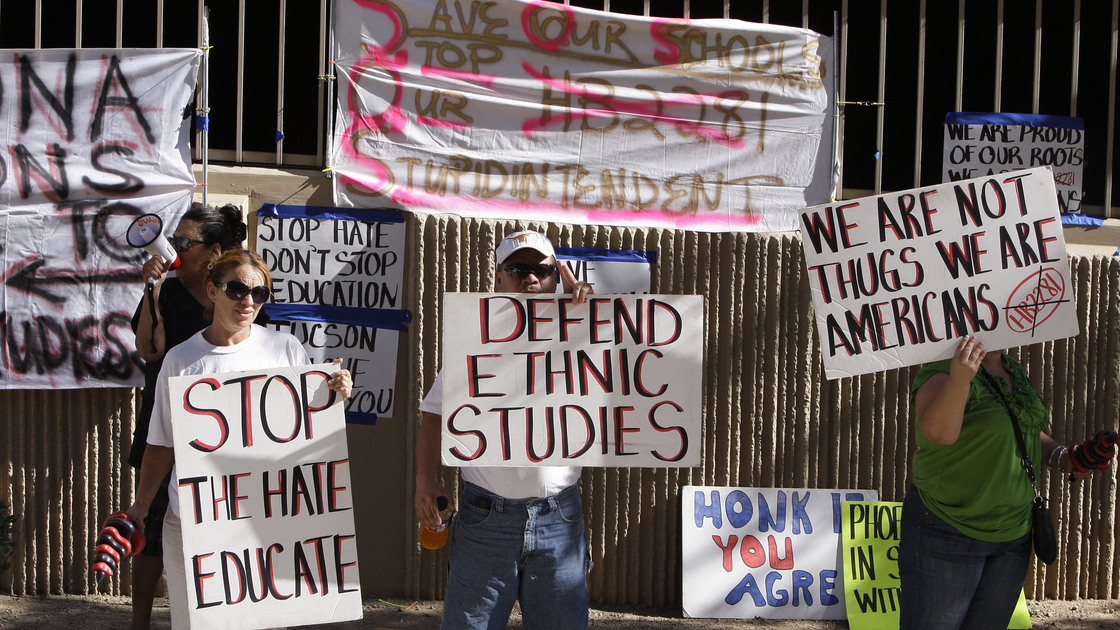

In 2010, state lawmakers in Arizona passed legislation that banned courses that “promote resentment toward a race or class of people.” But the legislation was, in reality, specifically targeting a Mexican American Studies program that started decades ago after Black and Latino students filed a desegregation lawsuit.

While Tucson initially kept the Mexican American Studies program, the school board caved in 2012 and ended it after threats that they would lose a significant portion of their state funding.

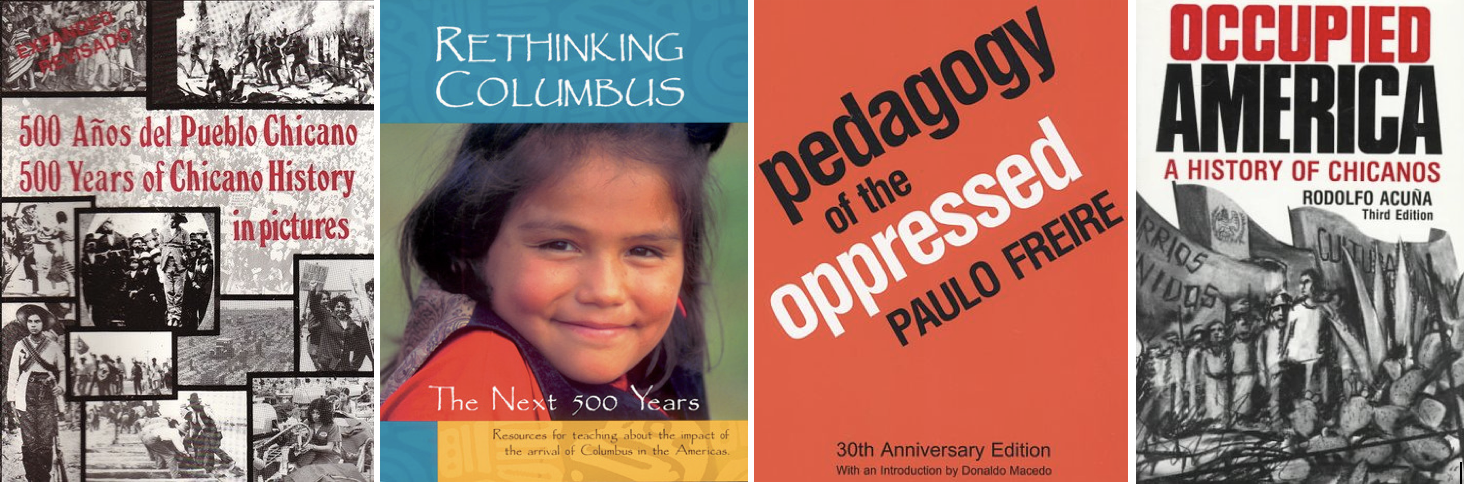

Part of ending the program meant banning the Rethinking Schools book, Rethinking Columbus, from classrooms along with Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Rodolfo Acuña’s Occupied America, and 500 Años del Pueblo Chicano/500 Years of Chicano History in Pictures by Elizabeth Martínez. In some instances, school authorities shocked students and confiscated the books during class.

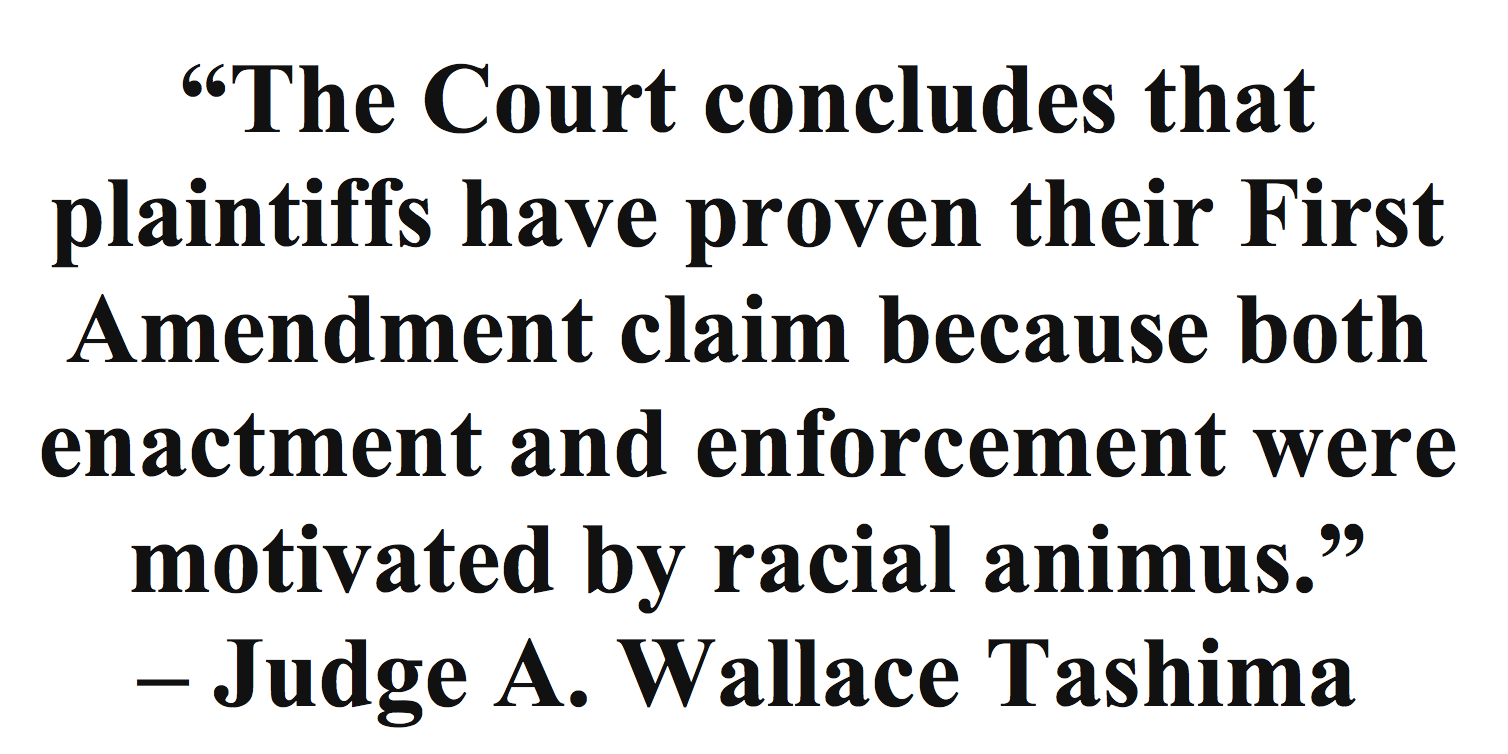

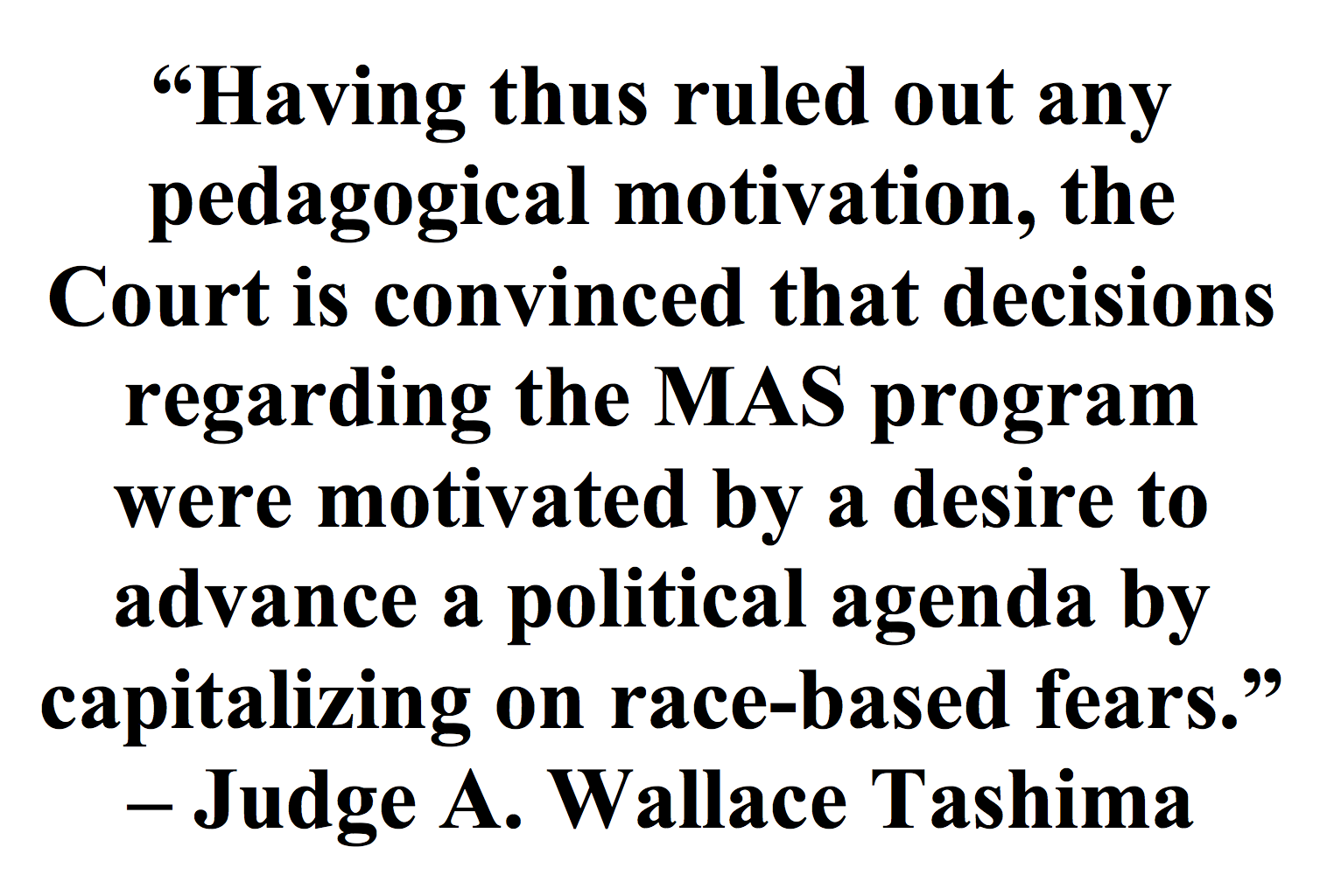

After several legal challenges, a federal judge last week ruled that the state of Arizona violated the constitutional rights of students by eliminating the program, and further went on to say that those who targeted it were motivated by racism and political opportunism.

Ari Bloomekatz talked with Dr. Curtis Acosta about the ruling for the Rethinking Schools blog. Acosta taught for 20 years in Tucson with the Mexican American Studies program, was a plaintiff in some of the initial legal challenges to the ban, and was an integral part of the challenge that eventually prevailed. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

***

ARI BLOOMEKATZ: Were you surprised by the verdict?

CURTIS ACOSTA: Shocked is better than surprised. At the end of closing arguments, Judge A. Wallace Tashima made it pretty clear — he said it was going to take him a couple weeks and it took him a little bit longer than that. And so we knew it could be any day, and I wasn’t surprised when it finally came, but we were definitely shocked with the intensity, and the care, and the totality of the victory. Judge Tashima’s legal analysis was just exhaustive in how he connected all of the actions, both in the production and construction of the law as being highly motivated by racial animus, to the application, to the enforcement. It was amazing, so that’s the reason the word shocked comes to mind. Just an incredible moment in history and an incredible punctuation to a long journey.

BLOOMEKATZ: It’s been a really long journey. How did you feel as your lawyer was telling you about the verdict?

ACOSTA: Absolutely shocked and in disbelief that it went our way so decisively. We knew we had the truth on our side, we knew what we went through. We knew who these people were who did this to us, and it’s just after so many years of being told you’re crazy, and we have tinfoil hats, and down is up and up is down, it was just shocking to hear the clarity and the affirmation, the validity of our program, of my colleagues and me. Our integrity was restored through a 9th Circuit judge. This is the United States of America judicial system, it’s pretty amazing to think that Mexican American students and the Mexican American community and ourselves as Mexican American teachers

could find this form of justice. We always believed in it, you have to, otherwise you don’t keep seeking justice and you quit and obviously we never quit. So the reaction was one of just exhilaration and disbelief. The disbelief part because that validation was never coming from the state of Arizona, and it certainly wasn’t coming from our school district who bent to the will of these racist actors. And it turned the tide of what was once a very beautiful community, a strong program that was leading the way for what we see now kind of catching fire throughout the nation, and so our humanity was restored to a large degree. I was just overwhelmed with excitement about the fact Judge Tashima saw what really happened and the evidence was overwhelming and he saw it clearly.

BLOOMEKATZ: What was it that really happened? What did Judge Tashima see? When you think of the evidence that he focused on, what do you think of?

ACOSTA: Well there are the obvious ones that started permeating the national consciousness — unfortunately posthumously after our program had been dismantled. Mr. Huppenthal’s racist blog post kind of revealed the person beneath the veneer. He tried to project a sense of this great patriarchal protector of these poor Mexican American kids and he was trying to do right by them. But doing right by them in his mind was ripping away the greatest program in the history of our state for these youth? That’s what I meant by down is up and up is down, that’s the world we were living in. And there was so much. The state has authority and so they spoke with that authority and many people believed it without really knowing the intimate details of what was going on or knowing these people. So his blog posts revealed, and also I think the Daily Show was another high watermark for getting into the consciousness of this type of ideology, this really harmful and almost a malicious mindset toward youth of color and communities of color. They used a lot of war-type of rhetoric toward us: Huppenthal

[wpvideo gVBF2i9D]

called his fight against our program the eternal battle of all time, and that he was waging a war against collectivism in the spirit of individualism they were doing this, almost like the Crusades. It was just really bizarre to live this, Ari, it’s amazing, there’s so much, but I think to answer your question there are small moments of the trial that stood out to me. I’d come home and vent to my wife, or to my dad and my step-mom, or to my friends or over the phone to my mom, to my colleagues in Mexican American Studies, I just couldn’t get over the fact that when I was being cross examined they were making a big deal, I mean, a big deal is like too colloquial. It was essential to their case to show that I was a damaging educator and a damaging educator who indoctrinated children into believing in a certain type of anti-American ideology. So what stood out to me is this moment: I’m being cross examined literally by the state of Arizona about my use of a speech by Ernesto Che Guevara and the state’s attorneys are trying to, are coming at me pretty hard, kind of bully type of tone about why was I teaching this speech, even missing the basic parts of my job description. They would be like: “You’re an English teacher, why are you teaching this?” And I’m like: “Well, I teach rhetoric. I’m trying to get the kids ready for college and rhetorical analysis is one of the hardest things to do.” And so it was continual other-izing of us, everything I was doing to them was so strange. So during my cross examination they came at it from that angle, that I’m not teaching appropriately because I’m teaching a speech and I’m an English teacher, so God knows what these people think we really do in our classrooms, because they have no idea what we’re supposed to do. So that was one piece. They would read part of Che’s very passionate perspective on the world — duh, he’s a Marxist — and he would read these excerpts to me and ask me if I thought it was appropriate to be reading this with my students. I said, “Absolutely.” I had colleagues who were of European American descent who taught European history and had pictures and posters of Marx and Engels on their wall, along with others, not just Marx and Engels, obviously, but other historical figures. They read the Communist Manifesto, they read Che Guevara or historical figures like that. As far as rhetoric, we read a whole diverse group of different voices to understand rhetorical traditions. But for us, since I’m a Chicano, since I’m Mexican American, there was this understanding that I couldn’t possibly do that in an responsible, scholarly way. Folks like Huppenthal and Horne see us as predatory, they see us as damaging, they see us as other, they see us as deficient, as in we can’t be scholarly, we can’t be academic, and Judge Tashima saw through all that and he emphasized that this was evidence that

their default setting wasn’t, “Oh, he’s doing it for rhetorical purposes or historical purposes.” Tashima said there’s so many reasons why a teacher would choose to teach that and they never asked that question, they just jumped right to indoctrination and right to the racial codes placed upon Mexican American individuals, the Mexican American community, and Mexican American scholars. It’s a real teacher kind of thing that I think the audience at Rethinking Schools could really connect to in many ways. The racial lens, the power lens, what we’ve been going through for years now, probably since Reagan came after teachers in “Nation at Risk,” just this battle we’ve been having, an unfortunate battle, a needless battle, with politicians telling us what’s best, how to best educate our children. And something we always laugh at amongst ourselves is how that’s working out for us, we always ask that question and it hasn’t been working out very well. But that was just one of those moments in Judge Tashima’s legal analysis and his findings that I thought indicated to me that he was really on his game, he was really listening to the arguments put forward.

BLOOMEKATZ: They went to the ends of the earth to go after this program. Why do you think they were just so absolutely threatened by it?

ACOSTA: We need to look to history, we need to look in the mirror at who we are, what this country has been built on, both the good and the tragic. And I’ll never forget, my good friend and our director of Mexican American Studies, Sean Arce — we were in a meeting like eight superintendents ago in TUSD, he was talking to the superintendent, saying you have to understand that Arizona, the state has, from the inception of our state, has had negative and hostile sentiments toward Mexican Americans. Mexicans first, and now Mexican Americans. It’s been with us for a long time, for over 100 years. So that’s still in the bloodstream. We can’t ignore the historical memory. It’s definitely still with us. Especially, I don’t think just as a country, and I haven’t for a long, long time now, thought that we do a very good job reflecting on our own history. It’s progress, progress, progress, usually it’s progress not socially but more through technology or through industry, progress that’s fueled by capitalism is what we concentrate on. Always looking forward and never looking back. And I think there’s a lot of value in looking back at our ancestors and gathering strength from the generations before us so that we can make better and informed decisions. And this comes from a literature teacher, so I’m sure all of my history and social studies colleagues, if they read this part, will be really excited. There’s value in the creative too, obviously, building new worlds and building art, but I think a lot of this comes from an ahistorical account of our country, of this state, of this continent. And so, when you start talking about sovereignty, you’ve got to ask questions about that. When somebody’s so fired up about the sovereignty of the United States of America, you want to ask questions. Those of us especially on the West Coast, we all studied 1776 as kids growing up — but I was a California kid. What was happening in 1776 in the Bay Area? Right? Or in Tucson? It’s more nuanced, it’s more human, it’s more multi-layered, and I think when we grow up with a singular narrative, we can’t see each other, we can’t humanize one another, because we really don’t know each other — which is again, the power, ironically, of ethnic studies. I used to say all the time, and I still do, that what these folks need is ethnic studies, the Hornes, the Huppenthals, they don’t know who we are. Even a lot of folks that think they know don’t know, and there has to

be some deference to that, and commitment, and so if we want to be who we already are, which is a nation that’s turning toward a multicultural, multilingual, pluralistic place — we’re always going to have English as this dominant language, I don’t think that’s to be debated — but to stomp out other languages, to stomp out other cultures, that’s a mindset that comes from a very dark part of the way this country was built, and I think we’re evidence of how one can get caught up in that. The tonic, the antidote to this is to learn about one another and to enjoy that. It’s something that our students and our classrooms were unabashed about loving one another and learning about each other and creating space for that, too. Our students know where the country’s going much more than we do, and we need to tap into that, and all that stuff frightens these folks. Another part of Tom Horne’s testimony that would be really valuable I think for Rethinking Schools readership is he was offended by how we talked about our pedagogy. I mean viscerally offended, I mean almost as if you were talking about his family, almost as if you were saying awful things to him personally. He is a person that doesn’t believe in constructivist and co-constructive-types of education. He was very firm: The teacher should teach, the students should listen. Very much this patriarchal, paternalistic, asymmetrical power relationship. He loves that. He thinks that’s wonderful. That one teacher should be the fount of information. It’s very much anti-Freire, anti-Paulo Freire and critical pedagogy. He thinks that’s damaging to students, literally said that, thus he thought we were damaging.

BLOOMEKATZ: This decision came down on the same day President Trump was in Arizona talking about pardoning Arpaio. How do you think about these two things happening on the same day? And how do you think about this decision happening context of the era of Trump?

ACOSTA: It’s funny. It might have been intentional and if not it was just a very interesting confluence of events. But I can’t get enough out of the idea that the current president continues to come back to Arizona — sorry, to Phoenix, I’ll be more specific — where our agitators came from, by the way, the actors that were found to be discriminatory and racially motivated against Mexican American students, they’re all from up there. So he goes to Phoenix, he’s come twice now when he’s in crisis, to almost get his bearings straight. As a person who grew up in California, who also loves Tucson, Arizona, it’s really difficult for me to know that this is where he comes to recharge that battery.

BLOOMEKATZ: Another question I have is about that transformation. What are the next steps, and what does this mean for the ethnic studies movement nationally?

ACOSTA: That one’s easier, the latter, so let’s start there. The question I was answering before the decision, was what happens if it doesn’t go your way. And of course it would set this awful precedent for all the areas of the country that have blossomed and are embracing Ethnic Studies after our untimely demise and it would unfortunately give the detractors a roadmap for how to challenge this in court and legal precedent. Thank God that didn’t happen; the nightmare scenario is gone. So instead: affirmation, validation, and precedent to anybody who tries to kick this stuff up. We’re still waiting on Judge Tashima’s remedies, so we’re not going to be sure about how this affects Tucson or Arizona for probably a few more weeks until Judge Tashima says this is what I expect to happen, this is what needs to happen. At the local level it’s going to be very interesting to see how they either ignore this, and they’ll try, I believe, they’ll try to ignore this, some of the politicians, especially on our school board. Or they’ll try to dig themselves out of this. But they have seven years of awful precedent, where our local school board never supported us, and so I’m really, really hopeful that we can get some leadership either at the board level but hopefully from the new superintendent and TUSD, and they can start anew and just say: Hey you know what, you all have blood on your hands, we’re moving forward because this program was great, it’s a part of our community, it’s a part of our history, and we need to embrace that and move forward.

BLOOMEKATZ: Why is this program so important for young people?

ACOSTA: I love answering that question. There are many particular, small, nuanced ways that our program may have been unique, but I think just flat out, if you boil it down, the space was powerful because it was a space where the students felt not only safe, but a space where they could be brave, a space where they could grow into their own strength. And we did that by being very real with our students about our expectations, how much we loved them, and what love means in a classroom and that we were working not only for them but for their grandparents, and for those that came before them, and that they needed to work for our children, and the young ones coming up, and that we had this understanding that we were in this beautiful space together to work to get better as human beings.

Ari Bloomekatz is the managing editor of Rethinking Schools. You can reach him at ari@rethinkingschools.org and can follow him, and Rethinking Schools, on Twitter @bloomekatz and @RethinkSchools.

Image credits (in order from top to bottom): Curtis Acosta and a group of Mexican American Studies students before the ban — provided by Acosta, books banned from classrooms, video by ABC15, illustration by Alec Dunn, photo from Arizona Community Press, flickr photo by Xomiele.

MORE FROM RETHINKING SCHOOLS RELATED TO THE MEXICAN AMERICAN STUDIES BAN IN TUCSON:

“Rethinking Columbus Banned in Tucson” and “Related Resources” at the Zinn Education Project by Bill Bigelow — https://rethinkingschoolsblog.com/2012/01/13/rethinking-columbus-banned-in-tucson/ and https://zinnedproject.org/2012/02/rethinking-columbus-banned-in-tucson/

“Sean Arce Honored — and Fired” — https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/short-stuff-5/

“From Johannesburg to Tucson” by Bill Bigelow — https://www.rethinkingschools.org/articles/from-johannesburg-to-tucson

“Precious Knowledge: Teaching Solidarity with Tucson” by Devin Carberry — https://www.rethinkingschools.org/articles/precious-knowledge-teaching-solidarity-with-tucson