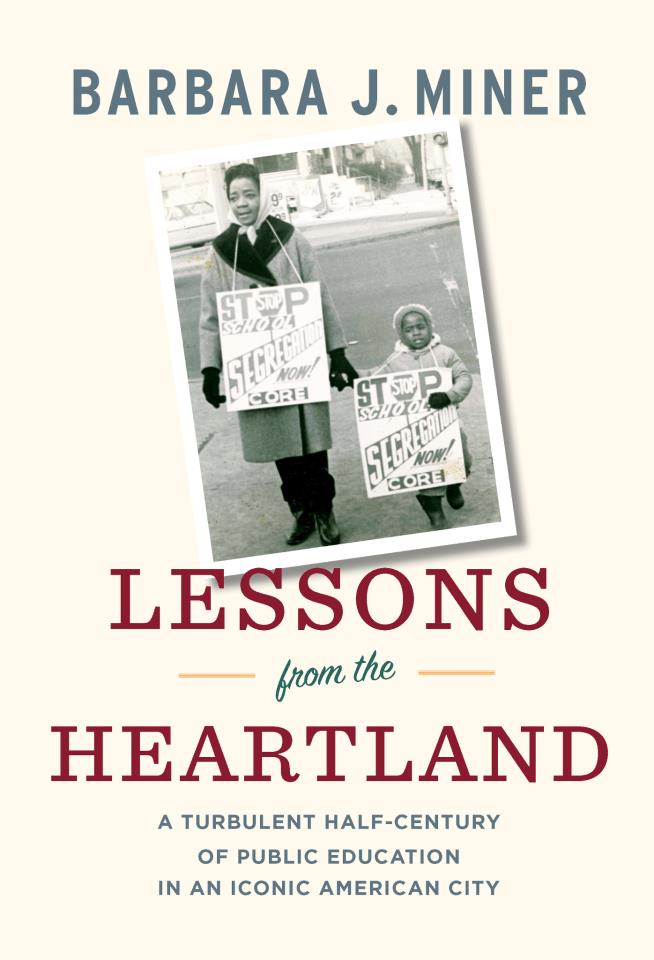

Editor’s note: Milwaukee is the latest city to erupt as a result of the police shooting of a Black man. As in Ferguson and Baltimore, the outrage in Milwaukee last weekend was rooted in long-standing anger toward the city’s multi-faceted racism. Milwaukee has been home to Rethinking Schools since our founding in 1986. Its schools cannot be separated from the city’s history of racism and racial violence. At her blog, “View from the Heartland,” Barbara Miner notes that “Milwaukee has a well-deserved reputation as perhaps the worst city in the country to raise an African American child. The city’s intense segregation and disparity did not happen overnight, but are the result of decades of practices and policies.” Miner is the former managing editor of Rethinking Schools and author of Lessons from the Heartland: A Turbulent Half Century of Public Education in an Iconic American City.

Following is an excerpt from Chapter 7 of Lessons from the Heartland. The chapter details the tumultuous events of the summer of 1967—both the city’s long-standing practice of valuing law and order over social justice, and the power of sustained grass-roots organizing.

Also see Miner’s 2012-2013 Rethinking Schools article on the origins of the school voucher movement in Milwaukee.

. . .

Chapter 7

1967–68: OPEN HOUSING MOVES TO CENTER STAGE

A Good Groppi Is a Dead Groppi.

—White supremacist sign during Milwaukee’s open housing marches

Except for Alderman Vel Phillips, who had been raising the issue for five years, no alderman would even consider the topic [of Open Housing]. “Seventeen white Milwaukee aldermen listened silently for 30 minutes Tuesday while their lone Negro colleague urged them to consider the adoption of a city fair housing ordinance,” the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote of the day’s events. “Then, without a word of comment or criticism, they voted to reject the proposal.”

Except for Alderman Vel Phillips, who had been raising the issue for five years, no alderman would even consider the topic [of Open Housing]. “Seventeen white Milwaukee aldermen listened silently for 30 minutes Tuesday while their lone Negro colleague urged them to consider the adoption of a city fair housing ordinance,” the Milwaukee Sentinel wrote of the day’s events. “Then, without a word of comment or criticism, they voted to reject the proposal.”

That summer, Phillips got support from outside the council. Father James Groppi and the NAACP Youth Council launched their Open Housing campaign, demanding the city pass legislation prohibiting discrimination in the sale, lease, and rental of housing property in Milwaukee. The campaign began with picketing outside the homes of prominent aldermen. On July 30, however, the marches were interrupted by what in Milwaukee are known as the 1967 Riots, part of a national explosion of pent-up Black rage.

In Milwaukee, as in other cities, anger in the Black community had long simmered over police brutality, unemployment, housing discrimination, school segregation, political and economic disenfranchisement, and the refusal of the white power structure to acknowledge the pressing need for change. On July 12, 1967, disturbances broke out in Newark, New Jersey, sparked when two white policemen arrested a black cabdriver for improperly passing them. Rumors that the cabbie had been killed led to six days of rage, leaving 26 people dead. Less than a week after the end of Newark’s riots, Detroit was in flames. Police action—this time against an after- hours bar—once again lit the fire. Disturbances grew so intense that not only did the governor call out the Michigan National Guard, but President Lyndon B. Johnson sent in army troops equipped with machine guns and tanks. The riots lasted five days, leaving 43 people dead and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed.

Milwaukee’s two-day upheaval began the night of July 30. By national standards, it was a relatively small disturbance. But it left whites in Milwaukee absolutely terrified, and it had a lasting impact on the city’s psyche.

The outbreak was fueled by rumors that a white policeman had killed an African American boy. Before long, the central city was beset with arson, gunshots, and looting. At around 3:00 a.m., Mayor Henry Maier instituted a 24-hour curfew and asked that the National Guard be called out. Only emergency and medical personnel were to leave their homes. Mail delivery and bus service were suspended. Those who violated the curfew were subject to immediate arrest.

The following morning, the city’s freeways and streets were empty and still. Six armored personnel carriers, each mounted with a .50 caliber machine gun, were ordered into the Milwaukee area. In the central city, the Milwaukee Journal reported, “every pedestrian and civilian vehicle was challenged by troops armed with bayonet-tipped rifles.” The riots left four people dead, almost a hundred injured, and 1,740 arrested.

Maier’s show of force was widely praised as saving the city from even more devastating consequences. At the same time, nothing of substance was done to alleviate the conditions leading to the unrest and anger in the African American community. [emphasis added.]

Shortly after the riots, Father Groppi and the NAACP Youth Council again took up their demands for open housing. And, just as they had crossed into the suburb of Wauwatosa, the civil rights demonstrators were not afraid to venture into white supremacist strongholds of Milwaukee. The decision led to the now legendary marches across the Sixteenth Street Viaduct separating the city’s downtown and Inner Core from the South Side.

On Monday, August 28, 1967, protesters gathered at St. Boniface in the central city. For the first time, they set out for the South Side, infamous as a stronghold of ethnic whites opposed to civil rights.

In a tribute to Father Groppi’s reputation among his former South Side parishioners, a small group of supportive whites from St. Veronica’s met the demonstrators at the beginning of their march across the bridge.1 By the time the protesters walked the half mile across the bridge, however, matters had changed. Most of the 3,000 whites on the other side were hostile, with signs that read “A Good Groppi Is a Dead Groppi.” Some yelled “Sieg heil,” others “Go back to Africa.” The marchers continued. Before long, counterdemonstrators along the march route were throwing bottles, stones, and chunks of wood at them. Another 5,000 white counterdemonstrators were waiting when the civil rights protesters arrived at their destination, Kosciuszko Park in the heart of the South Side.

The next night, Groppi and the Youth Council once again headed to the South Side. This time, an estimated 13,000 counterdemonstrators challenged them. Once again, Groppi and the marchers continued. After their march, they returned to their Freedom House in the Inner Core. At about 9:30 p.m., the house was on fire. Groppi said the police started the fire with tear gas; the police said a firebomb had been tossed into the house by an unknown person. When fire trucks arrived, the police would not let them near, citing reports of gunshots and fears of a sniper. “Youth council members said the gunshots came from police weapons,” writes journalist Frank Aukofer in his civil rights history of Milwaukee. “No arsonist or sniper ever was found.”2

After the day’s events, Mayor Maier banned nighttime demonstrations. On the night of August 30, however, Groppi held a rally at the burned-out Freedom House and led a march down city streets. Police ultimately arrested 58 people.3 The next night, declaring that Maier’s ban violated their First Amendment rights of assembly, marchers headed toward city hall. Some 137 people were arrested, including Alderman Phillips and Father Groppi.

Within days, the mayor was forced to lift his ban. Keeping their promise to continue marching every day, Father Groppi and the Youth Council didn’t stop even during the cold winter months, when temperatures sometimes dipped below zero.

On the South Side, white racists organized Milwaukee Citizens for Closed Housing, led by a white priest, Father Russell Witon. Decrying “forced open housing,” Father Witon and his supporters organized counterdemonstrations at the Milwaukee archdiocesan chancery office and in the central city. The group, however, had more fury than staying power. Their efforts dwindled.

Open housing supporters, meanwhile, refused to give up. Beginning with the walk across the Sixteenth Street Viaduct on August 28, 1967, they continued with marches and protests for 200 consecutive days.4 Finally, propelled by national events, Milwaukee’s power brokers realized they could no longer hold onto the past. On April 30, 1968, Milwaukee’s Common Council finally passed the open housing bill. The vote occurred two weeks after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated during his campaign in support of striking sanitation workers in Memphis. Riots of rage broke out across the country. In Milwaukee, an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 people marched somberly but peacefully through downtown.

The open housing legislation ended a long chapter in Milwaukee’s civil rights struggles, spanning almost a decade and involving the city’s seminal civil rights leaders and organizations. As early as 1961, [Desegregation activist Lloyd] Barbee helped organize a 13-day sit-in at the state capitol to ban discrimination in housing. In 1965, by that time a legislator, Barbee successfully co-sponsored statewide open housing legislation, but even supporters acknowledged it was a weak bill. In Milwaukee, meanwhile, Phillips and Groppi were pushing the more comprehensive local ordinance.

Barbee, Phillips, Groppi, and countless other activists easily moved between housing, school, and employment issues. They believed not only that the issues were inherently intertwined but also that they all had deep roots in overarching problems of racism and discrimination. …