“We can’t hunt [because] the ice is receding. People are going hungry,” says one voice. “Us, too! It’s food. We can’t grow it in the desert,” says another. The speakers are my students, who have taken on the voices of different indigenous people during a role play on the impact of climate change. The exercise is included in A People’s Curriculum for the Earth, a book I recently co-edited on teaching about the environmental crisis.

“We can’t hunt [because] the ice is receding. People are going hungry,” says one voice. “Us, too! It’s food. We can’t grow it in the desert,” says another. The speakers are my students, who have taken on the voices of different indigenous people during a role play on the impact of climate change. The exercise is included in A People’s Curriculum for the Earth, a book I recently co-edited on teaching about the environmental crisis.

The students are representing First Peoples as far-ranging as the Yup’ik of Alaska, the Bambara of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Aymara of Bolivia. The list is diverse, but all of the populations share one thing: They all suffer from catastrophic climate disruptions. Rather than simply lecturing or having students read about these changes, I want students to bring them to life in the classroom. Their task? To share experiences and articulate demands for the rest of the world — especially for those who control fossil fuel reserves.

One aim of the lesson is to help students recognize that some of the world’s poorest people — and those least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions — are the first to suffer the consequences of a warming planet. This is a point that was made dramatically by Pope Francis in his 2015 encyclical on the environment, in which the pontiff argues that those most threatened by climate change are the global poor — the billions of people around the world who are currently experiencing the worst effects of a rapidly changing climate. With them in mind, the pope called for an approach that “integrate(s) questions of justice in debates on the environment, so as to hear the cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor.” This “interdisciplinary” approach is one that educators also should embrace.

Our best curricular attempts to engage students come when we cross the boundaries of disciplines, in this case joining a scientific investigation of global warming with a social inquiry of how people are affected by a changing climate — and what we all can do about it.

‘Fix the problems…’

One lesson I’ve taught exemplifies these connections and is included in A People’s Curriculum for the Earth. It is “The Mystery of the 3 Scary Numbers,” written by co-editor Bill Bigelow, the curriculum editor of Rethinking Schools. In this lesson, students receive clues and try to figure out the significance of the “three scary numbers”: 2-degrees Celsius, the temperature rise that, if exceeded, would likely trigger a point of climate noreturn; 565 gigatons of carbon, the amount of carbon that can be burned without pushing a 2-degree rise; and 2,795 gigatons of carbon, the amount of proven reserves of coal, oil, and gas that corporations and countries have ready to exploit and burn. During class, students mingle to discuss their clues, and slowly piece together the frightening significance of these numbers. It’s a math lesson, a science lesson, and a social studies lesson all rolled into one.

Afterward, in class discussion, students wrestle with the implications of this playful, but sobering, activity. Should fossil fuel companies be left to decide the fate of the Earth? If not, how should the rest of us respond?

Our classrooms are an important venue in the struggle for a livable planet. We have an opportunity to put the most important crisis facing humanity at the center of our curriculum — and to do it in a way that brings hope to our students, who have been told for much of their lives that it’s up to their generation to “fix the problems” being passed on to them. If we can bring to life the stories of indigenous groups, anti-fossil fuel activists, and communities around the world who are working toward a saner and more equitable social and ecological order, our students can begin to see themselves as part of a larger movement.

Teaching about climate change can be overwhelming. In fact, it probably should overwhelm us at times if we grasp the enormity of the issues in the way scientists suggest we should. But by teaching the crisis through imaginative curriculum, and telling the stories of the people most affected and the movements struggling for environmental and social justice, our students can also find the hope and collective strength to work toward a better future.

A Classroom Resource Guide: CLIMATE CHANGE

These are just a few of the resources compiled by NEA Healthy Futures to help educators teach about climate change. For more, visit nea.org/climatechange.

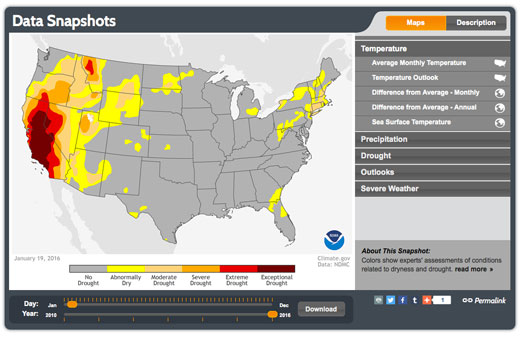

- Teaching Climate, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — Provides resources for teachers, including videos, demos and experiments, and interactive tools.

- Climate Change Live: A Distance Learning Adventure — A website from the U.S. Forest Service and its partners provides links to educator webinars, lesson plans, and more.

- Climate Kids: NASA’s Eyes on the Earth, NASA — Includes links to online games and a visually appealing discussion guide for teachers.

Tim Swinehart teaches at Lincoln High School in Portland, Ore., and is a member of the Portland Association of Teachers (NEA). He coedited A People’s Curriculum for the Earth: Teaching Climate Change and the Environmental Crisis, available at rethinkingschools.org.

Originally published at www.nea.org.